Following the war for independence, American politics split between those supporting a strong federal government and those favoring greater self-determination for the states. In the South, climate conditions led to dependence on agriculture, the rural economy of the southern states producing cotton, rice, sugar, indigo and tobacco. Colder states to the north tended to develop manufacturing economies, urban centers growing up in service to hubs of transportation and the production of manufactured goods.

During the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. Most of this revenue was collected in the South, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of federal spending was directed toward the North, toward the construction of roads, canals and other infrastructure.

The debate over economic issues and rights of self-determination, so-called ‘state’s rights’, grew and sharpened in 1828 with the threatened secession of South Carolina and the “nullification crisis” of 1832-33. South Carolina declared such tariffs unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the state. A Cartoon from the era says it all – Northern domestic manufacturers getting fat at the expense of impoverishing the South under protective tariffs.

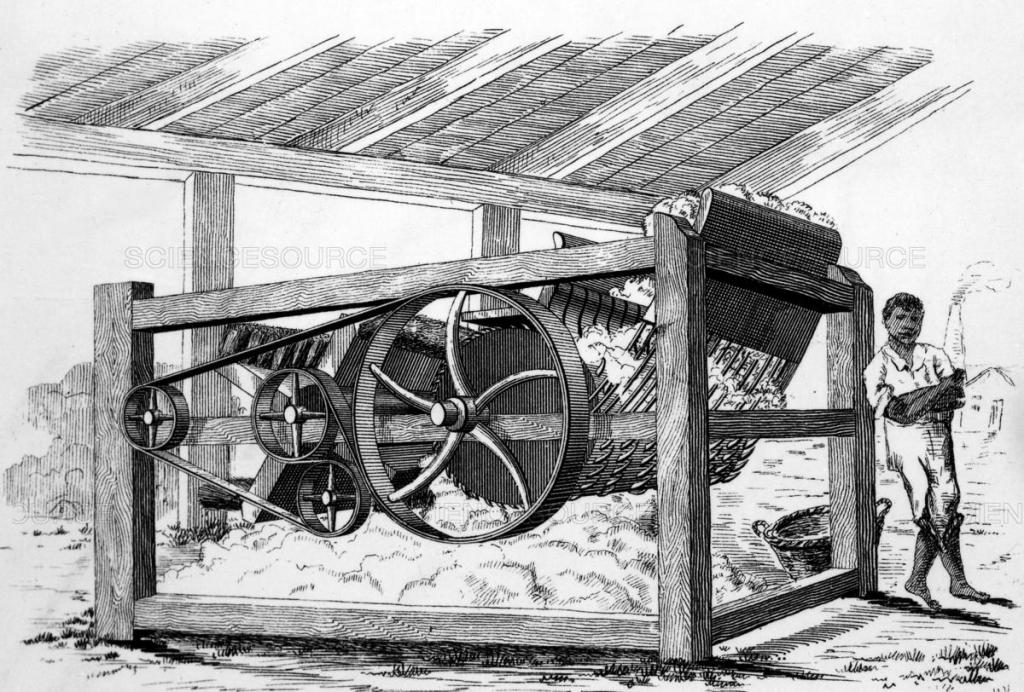

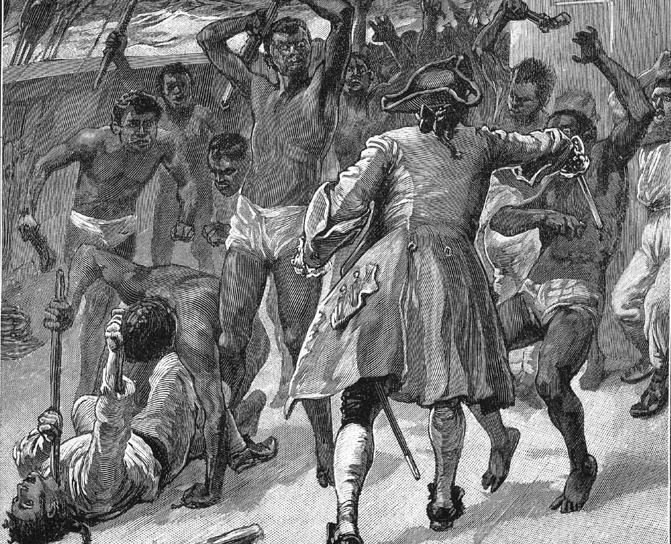

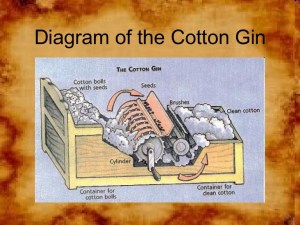

Chattel slavery came to the Americas well before the colonial era, from Canada to Mexico to Brazil and around the world. Moral objections to what was clearly a repugnant practice could be found throughout, but economic forces had as much to do with ending the practice as any other. The “peculiar institution” died out first in the colder regions of the US and may have done so in warmer climes as well, but for Eli Whitney’s invention of a cotton engine (‘gin’) in 1792.

Removing cotton seeds by hand requires ten man-hours to remove the seeds from a single pound of cotton. By comparison, a cotton gin can process about a thousand pounds a day at comparatively little expense.

The year of Whitney’s invention, the South exported 138,000 pounds a year to Europe and the northern colonies. Sixty years later, Britain alone was importing 600 million pounds a year of the stuff, from the American south. Cotton was King, and with good reason. The crop is easily grown, is more easily transportable and can be stored indefinitely, compared with food crops. The southern economy turned overwhelmingly to this one crop and with it, the need for cheap, plentiful labor.

By then the issue of slavery was so joined and intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The short-lived “Wilmot Proviso” of 1846 sought to ban slavery in new territories, after which the Compromise of 1850 attempted to strike a balance. The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, basically repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing settlers to determine their own way through popular sovereignty.

This attempt to democratize the issue instead had the effect of drawing up battle lines. Pro-slavery forces established a territorial capital in Lecompton, while “antis” set up an alternative government in Topeka.

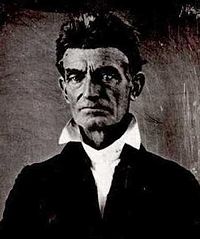

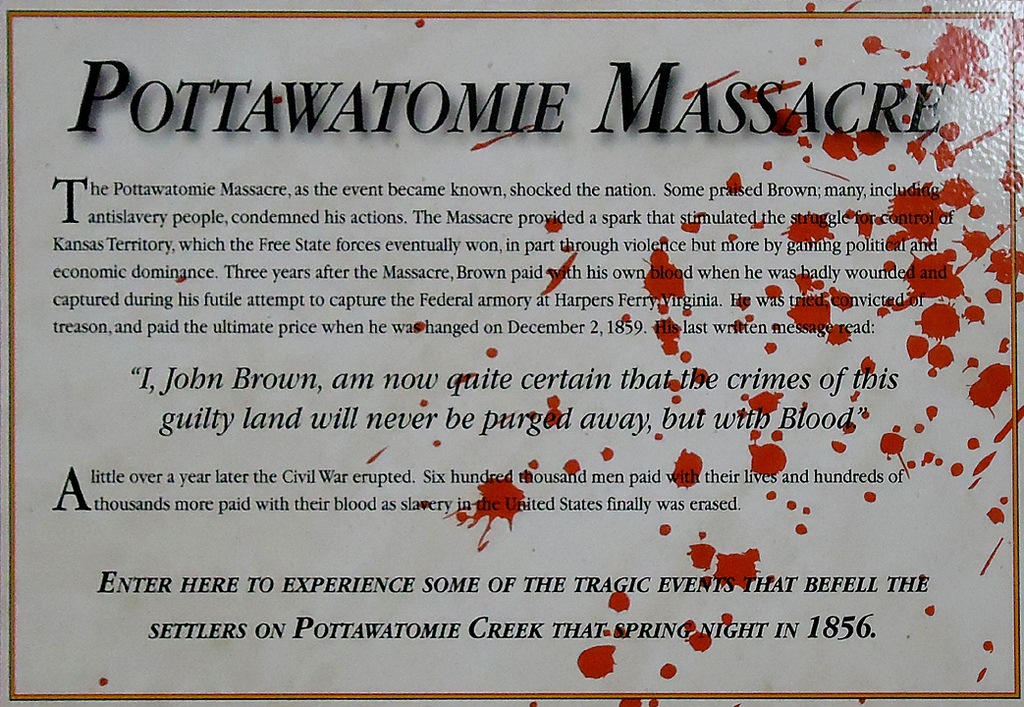

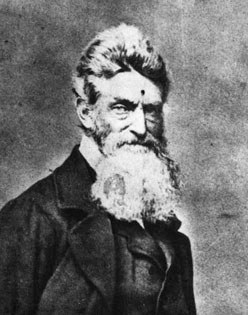

John Brown Sr. came to the Kansas Territory as a result of violence, sparked by the expansion of slavery into the Kansas-Nebraska territories between 1854 and 1861, a period known as “Bleeding Kansas”. To some, the man was a hero. To others he was a kook. The devil incarnate. A radical abolitionist and unwavering opponent of the “peculiar institution” of slavery, John Brown believed that armed confrontation was the only way to bring it to an end.

In Washington DC, a United states Senator was beaten nearly to death on the floor of the Senate, by a member of the House of Representatives. The following day Brown and four of his sons: Frederick, Owen, Salmon, and Oliver, along with Thomas Weiner and James Townsley, set out on a “secret expedition”.

The group camped between two deep ravines off the road that night, remaining in hiding until sometime after dark on the 24th. Late that night, they stopped at the house of James P. Doyle, ordering him and his two adult sons, William and Drury, to go with them as prisoners. Doyle’s wife pleaded for the life of her 16 year old son John, whom the Brown party left behind. The other three, all former slave catchers, were led into the darkness. Owen Brown and one of his brothers murdered the brothers with broadswords. John Brown, Sr. fired the coup de grace into James Doyle’s head to ensure that he was dead.

The group went on to the house of Allen Wilkinson, where he too was brought out into the darkness and murdered with broadswords. Sometime after midnight, the group forced their way into the cabin of James Harris. His two house guests were spared after interrogation, but Wilkinson was led to the banks of Pottawatomie Creek where he too was slaughtered.

There had been 8 killings to date in the Kansas Territory; Brown and his party had just murdered five in a single night. The massacre lit a powder keg of violence in the days that followed. Twenty-nine people died on both sides in the next three months alone.

Brown would go on to participate in the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie in the Kansas Territory. Brown lead a group to the armory in Harper’s Ferry Virginia in a hare brained scheme to capture the weapons contained there and trigger a slave revolt. The raid was ended by a US Army force under Colonel Robert E. Lee, and a young Army lieutenant named James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart.

Brown supporters blamed the 1856 massacre on everything from defending the honor of the Brown family women, to self defense, to a response to threats of violence from pro slavery forces. Free Stater and future Kansas Governor Charles Robinson may have had the last word when he said, “Had all men been killed in Kansas who indulged in such threats, there would have been none left to bury the dead.”

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859.

The 80-year-old nation forged inexorably onward, toward a Civil War that would kill more Americans than every conflict from the American Revolution to the War on Terror, combined.

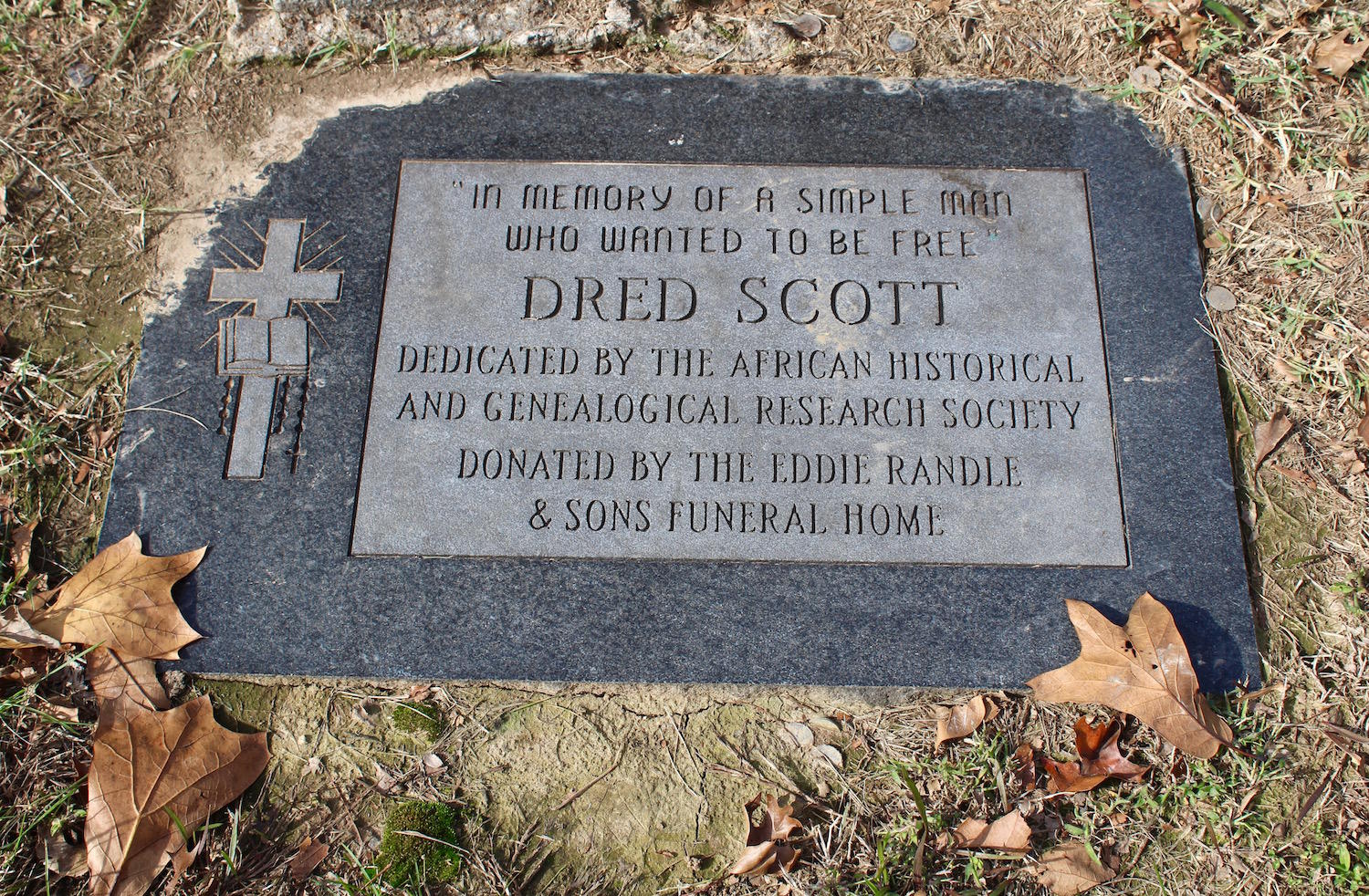

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

In the next few days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals. Four months of partisan violence and depredation ensued. Small armies formed up across eastern Kansas, clashing at Black Jack, Franklin, Fort Saunders, Hickory Point, Slough Creek, and Osawatomie

In the next few days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals. Four months of partisan violence and depredation ensued. Small armies formed up across eastern Kansas, clashing at Black Jack, Franklin, Fort Saunders, Hickory Point, Slough Creek, and Osawatomie

You must be logged in to post a comment.