Former Boston Braves pitcher Max Surkont once quipped, “Baseball was never meant to be taken seriously — if it were, we would play it with a javelin instead of a ball”. I’m not sure about javelins, but I do know how much we all love to see to see that ball, hit out of the park.

Yes, home runs ae fun, but that’s not always how the game was played. The “Hitless Wonders” of the Chicago White Sox won the 1906 World Series with a .230 club batting average. Manager Fielder Jones said “This should prove that leather is mightier than wood”. Fielder Allison Jones. Yeah, that’s the man’s real name. Is that the greatest baseball name ever, or what?

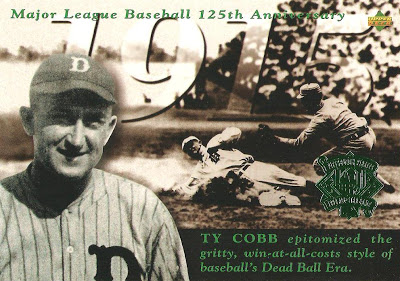

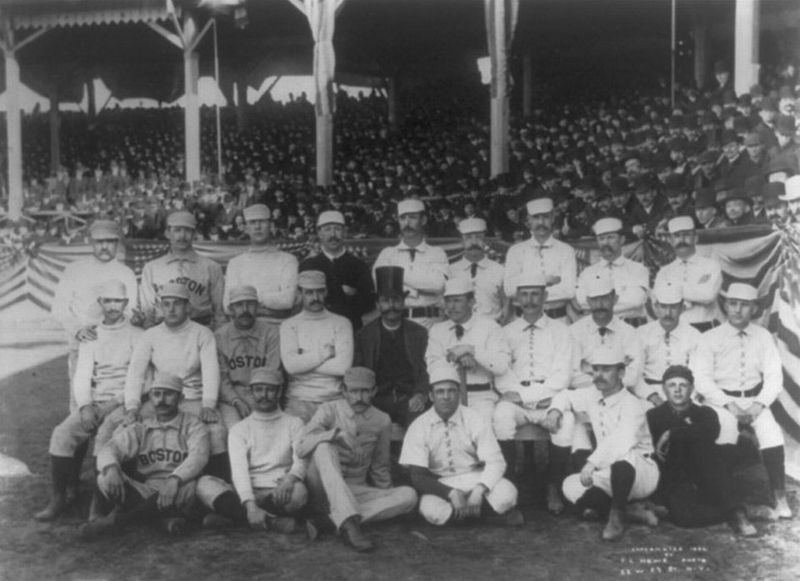

This was the “dead-ball” era, when an “inside baseball” style of play relied on stolen bases, hit-and-run plays and, more than anything else, speed.

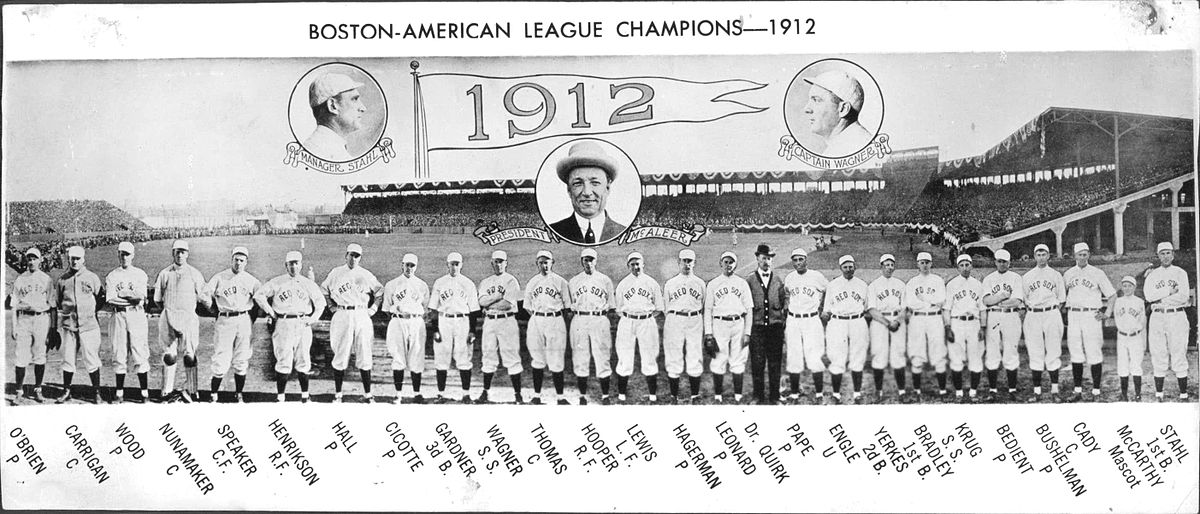

That’s not to say there were no power hitters. In some ways, a triple may be more difficult than a home run, requiring a runner to cover three bases in the face of a defense still in possession of the ball. Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Owen “Chief” Wilson set a record of 36 triples in 1912. “Wahoo” Sam Crawford hit a career record 309 triples during 18 years in Major League Baseball, playing for the Cincinnati Reds and Detroit tigers between 1899 and 1917. 100 years later, it’s unlikely that either record will ever be broken.

In his 1994 television miniseries “Baseball”, Ken Burns commented that “Part of every pitcher’s job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field… They smeared it with dirt, licorice, and tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred… and as it came over the plate, [the ball] was very hard to see.”

Spitballs lessened the natural friction with a pitcher’s fingers, reducing backspin and causing the ball to drop. Sandpapered, cut or scarred balls tended to “break” to the side of the scuff mark. Balls were rarely replaced in those days. By the end of a game, the ball was scarred, misshapen and entirely unpredictable.

On February 10, 1920, Major League Baseball outlawed “doctored” pitches, though it remained customary to play an entire game with the same ball.

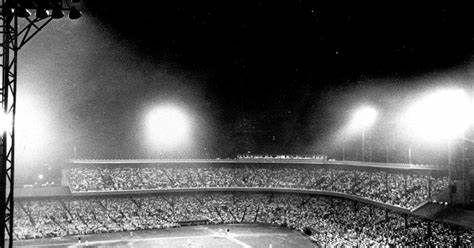

The first ever game to be played “under the lights” was forty years in the past in 1920, but it would be another 15 before the practice became widespread.

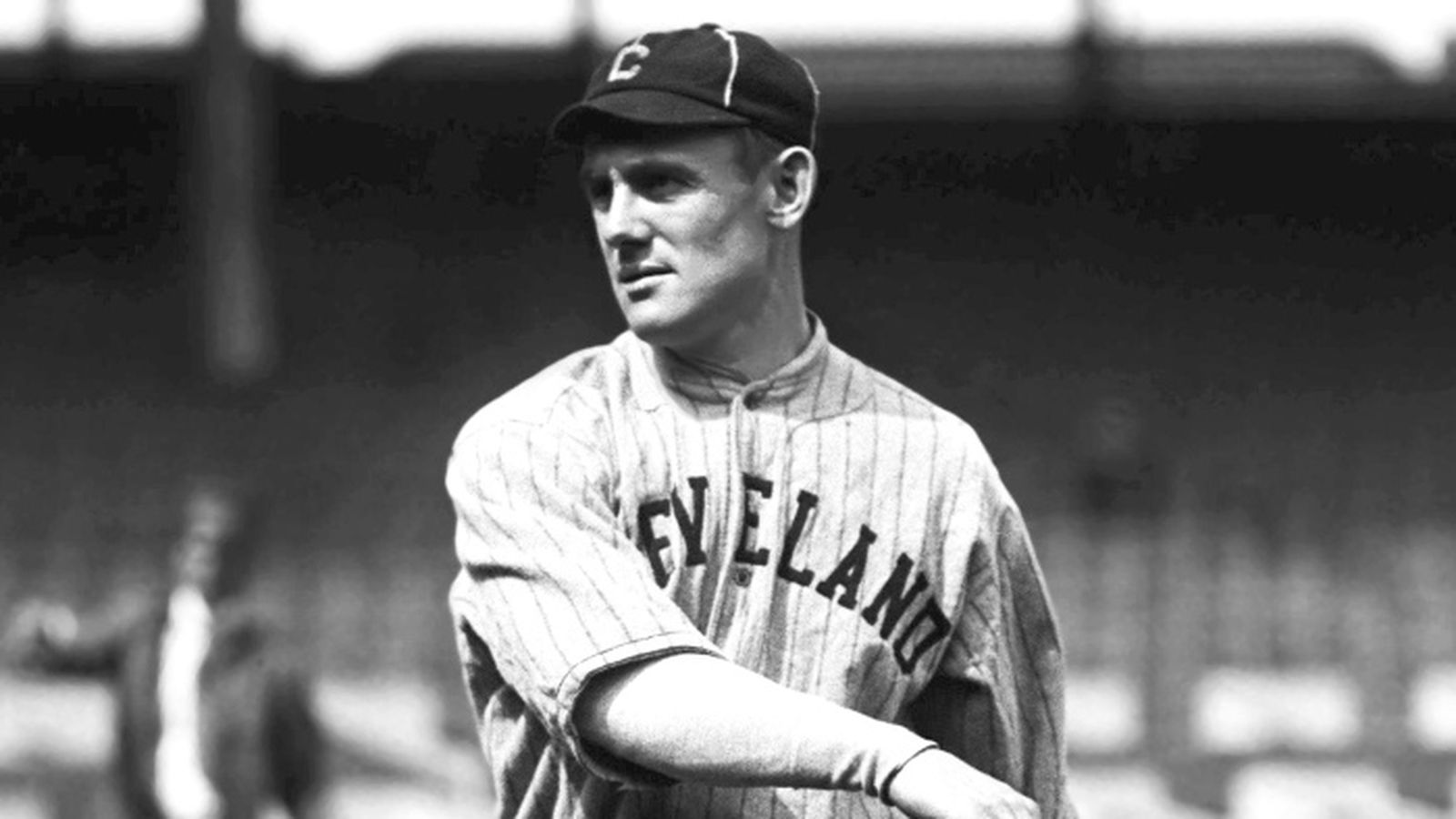

It was late afternoon on August 16 of that year, when the Cleveland Indians were playing the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman took the plate in the top of the 5th, facing “submarine” pitcher Carl Mays. These are not to be confused with the windmill underhand pitches we see in softball. Submarine pitchers throw side-arm to under-handed, their upper bodies so low that some of them scuff their hands on the ground, the ball rising as it approaches the strike zone.

Chapman never moved, he seems not to have seen it coming. The crack of the ball hitting his head was so loud that Mays thought he had hit the end of the bat, fielding the ball and throwing to first for the out. Wally Pipp, the first baseman better known for losing his starting position to Lou Gehrig because of a headache, immediately knew something was wrong. The batter made no effort to run, but slowly collapsed to the ground with blood streaming from his left ear.

29-year-old Ray Chapman had said this was his last year playing ball. He wanted to spend more time in the family business he had just married into. The man was right. Raymond Johnson Chapman died 12 hours later, the only player in the history of Major League Baseball, to die from injuries sustained during a game.

The age of one-ball-per-game died with Ray Chapman, and with it the era of the dead ball. The lively ball era, had begun. Batters loved it, but pitchers complained about having to handle all those shiny new balls.

MLB rule #3.01(c) states that “Before the game begins the umpire shall…Receive from the home club a supply of regulation baseballs, the number and make to be certified to the home club by the league president. The umpire shall inspect the baseballs and ensure they are regulation baseballs and that they are properly rubbed so that the gloss is removed. The umpire shall be the sole judge of the fitness of the balls to be used in the game”.

Umpires would “prep” the ball using a mixture of water and dirt from the field, but this resulted in too-soft covers, vulnerable to tampering. Something had to take the shine off the ball without softening the cover.

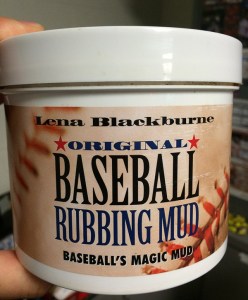

Philadelphia Athletics third base coach Lena Blackburne took up the challenge in 1938, scouring the riverbanks of New Jersey for just the right mud. Blackburne found his mud hole, describing the stuff as “resembling a cross between chocolate pudding and whipped cold cream”. By his death in the late fifties, Blackburne was selling his “Baseball Rubbing Mud” to every major league ball club in the country, and most minor league teams.

In a world where classified information is kept on personal email servers, there are still some secrets so pinky-swear-double-probation-secret that the truth may Never be known. Among them Facebook “Community Standards” algorithms, the formula for Coca Cola, and the Secret Swamp where Lena Blackburne’s Baseball Rubbing Mud comes from.

Nobody knows, but one thing is certain. The first pitchers will show up to the first spring training camp, a few short days short days from now. From 1938 to the present day, every baseball thrown from pre-season to the World Series, will be first de-glossed using Lena Blackburne’s famous, Baseball Rubbing Mud.

Play ball.

As the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel basket. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

As the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel basket. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

This was the “dead-ball” era of the Major Leagues, an “inside baseball” style relying on stolen bases, hit-and-run plays and, more than anything, speed.

This was the “dead-ball” era of the Major Leagues, an “inside baseball” style relying on stolen bases, hit-and-run plays and, more than anything, speed. Spitballs lessened the natural friction with a pitcher’s fingers, reducing backspin and causing the ball to drop. Sandpapered, cut or scarred balls tended to “break” to the side of the scuff mark. Balls were rarely replaced in those days. By the end of a game, the ball was scarred, misshapen and entirely unpredictable. Major League Baseball outlawed “doctored” pitches on February 10, 1920, though it remained customary to play an entire game with the same ball.

Spitballs lessened the natural friction with a pitcher’s fingers, reducing backspin and causing the ball to drop. Sandpapered, cut or scarred balls tended to “break” to the side of the scuff mark. Balls were rarely replaced in those days. By the end of a game, the ball was scarred, misshapen and entirely unpredictable. Major League Baseball outlawed “doctored” pitches on February 10, 1920, though it remained customary to play an entire game with the same ball. A submarine pitch is not to be confused with the windmill underhand pitch we see in softball. Submarine pitchers throw side-arm to under-handed, with upper bodies so low that some scuff their hands on the ground, the ball rising as it approaches the strike zone.

A submarine pitch is not to be confused with the windmill underhand pitch we see in softball. Submarine pitchers throw side-arm to under-handed, with upper bodies so low that some scuff their hands on the ground, the ball rising as it approaches the strike zone.

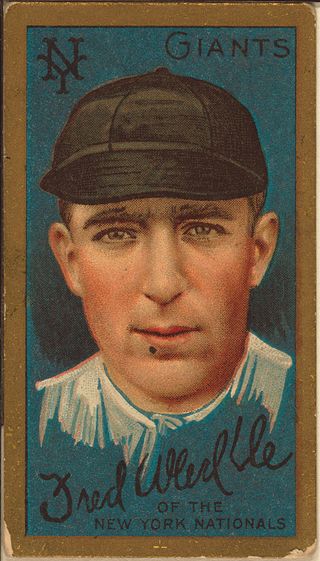

Merkle thought so too, and ran to the Giants’ clubhouse, never touching second base.

Merkle thought so too, and ran to the Giants’ clubhouse, never touching second base.

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

In 1912, the Doves adopted an official name of their own. National League franchise owner James Gaffney was a member of Tammany Hall, the political machine that ruled New York, between 1789 and 1967. Tammany Hall’s symbol was an Indian chief, its headquarters called a “wigwam”. So it was that, the oldest franchise in major league baseball, came to be called “the Braves”.

In 1912, the Doves adopted an official name of their own. National League franchise owner James Gaffney was a member of Tammany Hall, the political machine that ruled New York, between 1789 and 1967. Tammany Hall’s symbol was an Indian chief, its headquarters called a “wigwam”. So it was that, the oldest franchise in major league baseball, came to be called “the Braves”.

1915 ushered in a 20-year losing streak for the Braves. Ironically, it was Babe Ruth who was expected to pull it all together, when Braves President Emil Fuchs brought the Bambino back to Boston in 1935.

1915 ushered in a 20-year losing streak for the Braves. Ironically, it was Babe Ruth who was expected to pull it all together, when Braves President Emil Fuchs brought the Bambino back to Boston in 1935.

You must be logged in to post a comment.