In living memory, France and Great Britain have always been allies. In war and peace from the Great War to World War 2 to the present day, but such was not always the case. Between the Norman Invasion of 1066 and the Napoleonic Wars of 1802-1815, the two allies have found themselves in a state of war no fewer than forty times.

Throughout most of that history, the two sides would clash until one or the other ran out of money, when yet another treaty would be trotted out and signed.

New taxes would be levied to bolster the King’s treasury, and one or the other would be back for another round. The cycle began to change in the late 17th century for reasons which may be summed up with a single word. Debt.

In the time of Henry VIII, British military outlays as a percentage of central government expenses averaged 29.4%. By 1694 the Nine Years’ War had left the English Government’s finances in tatters. £1.2 million were borrowed by the national treasury at a rate of 8 percent from the newly formed Bank of England.

The age of national deficit financing, had arrived.

In one of the earliest known debt issues in history, Prime Minister Henry Pelham converted the entire national debt into consolidated annuities known as “consols”, in 1752. Consols paid interest like regular bonds, with no requirement that the government ever repay the face value. 18th century British debt soared as high as 74.6%, and never dropped below 55%.

The Seven Years’ War alone, fought on a global scale between 1756 to 1763, saw British debt double to the unprecedented sum of £150 million, straining the national economy.

American colonists experienced the conflict in the form of the French and Indian War, for which the Crown laid out £70,000,000. The British government saw its American colonies as beneficiaries of their expense, while the tax burden on the colonists themselves remained comparatively light.

For American colonists, the never ending succession of English wars had accustomed them to running their own affairs.

The “Townshend Revenue Acts” of 1767 sought to force American colonies to pick up the tab for their own administration, a perfectly reasonable idea in the British mind. The colonists had other ideas. Few objected to the amount of taxation as much as whether the British had the right to tax them at all. They were deeply suspicious of the motives behind these new taxes, and were not about to be subjugated by a distant monarch.

The political atmosphere was brittle in 1768, as troops were sent to Boston to enforce the will of the King. Rioters ransacked the home of a newly appointed stamp commissioner, who resigned the post following day. No stamp commissioner was actually tarred and feathered, a barbarity which had been around since the days of Richard III “Lionheart”, though several such incidents occurred at New England seaports. More than a few loyalists were ridden out of town on the backs of mules.

The Massachusetts House of Representatives sent a petition to King George III asking for the repeal of the Townshend Act. A Circular Letter sent to the other colonial assemblies, called for a boycott of merchants importing those goods affected by the act. Lord Hillsborough responded with a letter of his own, instructing colonial governors in America to dissolve those assemblies which responded to the Massachusetts body.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston.

On February 22, 1770, 11-year-old Christopher Seider joined a mob outside the shop of loyalist Theophilus Lillie. Customs official Ebenezer Richardson attempted to disperse the crowd. Soon the mob was outside his North End home. Rocks were thrown and windows broken. One hit Richardson’s wife. Ebenezer Richardson fired into the crowd, striking Christopher Seider. By nightfall, the boy was dead. 2,000 locals attended the funeral of this, the first victim of the American Revolution.

Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs.

Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs.

Weeks earlier, the wigmaker had given British Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch, a shave.

A cocky 13-year old, Garrick spotted the officer and taunted the man, yelling “There goes the fellow that won’t pay my master!”

Goldfinch had paid the man the day before. The officer wasn’t about to respond to an insult from some snotty kid but private Hugh White, on guard outside the State House on King Street, took the bait. White said the boy should be more respectful and struck him on the head, with his musket. Garrick’s buddy and fellow wigmaker’s apprentice Bartholomew Broaders began to argue with White, as a crowd gathered ’round to watch.

As the evening pressed on, church bells began to ring. The crowd, now fifty and growing and led by the mixed-race former slave-turned sailor Crispus Attucks threw taunts and insults, spitting and daring Private White to fire his weapon. The swelling mob turned from boisterous to angry as White took a more defensible position, against the State House steps. Runners alerted Officer of the Watch Captain Thomas Preston to the situation, who dispatched a non-commissioned officer and six privates of the 29th Regiment of Foot, to back up Private White.

Bayonets fixed, the eight took a semi-circular defensive position with Preston himself, in the lead. The crowd, now numbering in the hundreds, began to throw snowballs. Then stones and other objects. Private Hugh Montgomery was knocked to the ground and, infuriated, came up shooting.

The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

The mob moved away from the spot on King Street, now State Street, but continued to grow in the nearby streets. Speaking from a balcony, acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson was able to restore some semblance of order, only by promising a full and fair inquiry.

Future President John Adams defended the troopers assisted by Josiah Quincy and Loyalist Robert Auchmuty. Massachusetts Solicitor General Samuel Quincy and private attorney Robert Treat Paine handled the prosecution in two separate trials, one for Captain Preston, the other for the eight enlisted soldiers.

Two were convicted but escaped hanging, by invoking a medieval legal remnant called “benefit of clergy”. Each would be branded on the thumb in open court with “M” for murder. The others were acquitted, leaving both sides complaining of unfair treatment. It was the first time a judge used the phrase “reasonable doubt.”

The only conservative revolution in history, was fewer than six years in the future.

There is a circle of stones in front of the Old State House on what is now State Street, marking the site of the Boston Massacre. British taxpayers continue to this day, to pay interest on the debt left to them, by the decisions of their ancestors.

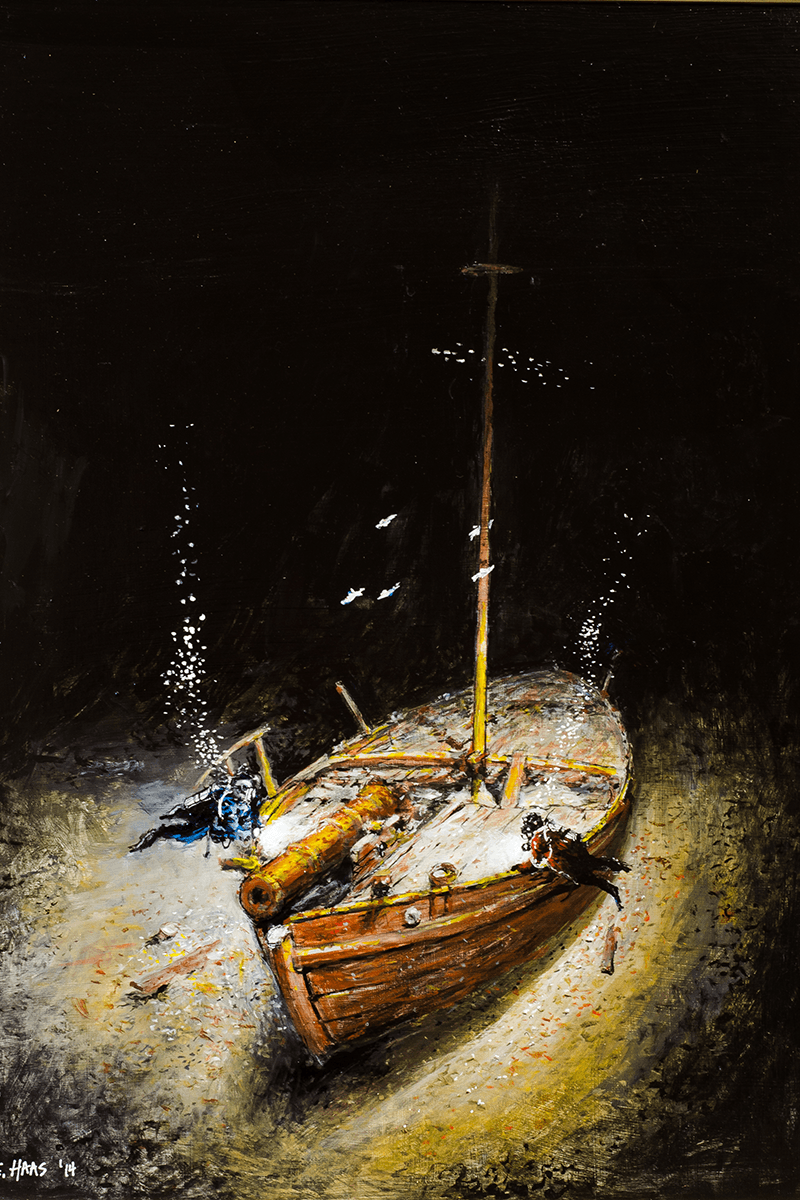

Hermanus Schuyler oversaw the effort, while military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin was in charge of outfitting. Gates asked General Benedict Arnold, an experienced ship’s captain, to spearhead the effort, explaining “I am intirely uninform’d as to Marine Affairs”.

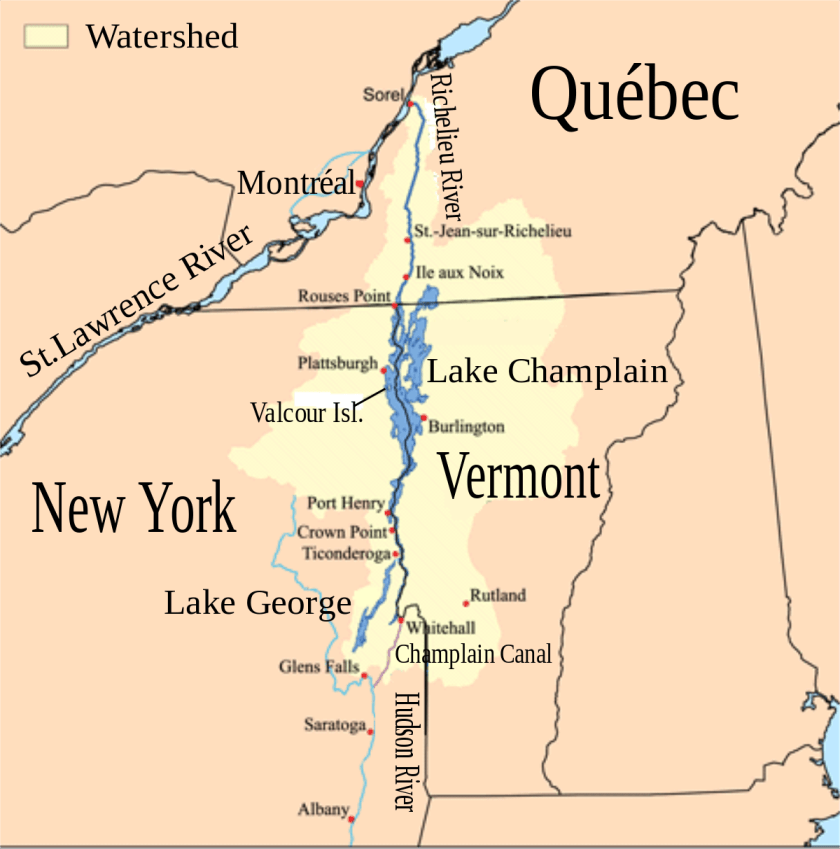

Hermanus Schuyler oversaw the effort, while military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin was in charge of outfitting. Gates asked General Benedict Arnold, an experienced ship’s captain, to spearhead the effort, explaining “I am intirely uninform’d as to Marine Affairs”. As the two sides closed in the early days of October, General Arnold knew he was at a disadvantage. The element of surprise was going to be critical. Arnold chose a small strait to the west of Valcour Island, where he was hidden from the main part of the lake. There he drew his small fleet into a crescent formation, and waited.

As the two sides closed in the early days of October, General Arnold knew he was at a disadvantage. The element of surprise was going to be critical. Arnold chose a small strait to the west of Valcour Island, where he was hidden from the main part of the lake. There he drew his small fleet into a crescent formation, and waited.

Seven years later during the French & Indian War, Rogers’ Rangers were ordered to attack the Abenaki village with John Stark, second in command. Stark refused to accompany the attacking force out of respect for his Indian foster family, returning instead to Derryfield and his wife Molly, whom he had married the year before.

Seven years later during the French & Indian War, Rogers’ Rangers were ordered to attack the Abenaki village with John Stark, second in command. Stark refused to accompany the attacking force out of respect for his Indian foster family, returning instead to Derryfield and his wife Molly, whom he had married the year before.

A man who should have gone into history among the top tier of American Founding Fathers, the future turncoat Benedict Arnold, arrived with Connecticut militia to support the siege. Arnold informed the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that Fort Ticonderoga, located along the southern end of Lake Champlain in northern New York, was bristling with cannon and other military stores. Furthermore, the place was lightly defended.

A man who should have gone into history among the top tier of American Founding Fathers, the future turncoat Benedict Arnold, arrived with Connecticut militia to support the siege. Arnold informed the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that Fort Ticonderoga, located along the southern end of Lake Champlain in northern New York, was bristling with cannon and other military stores. Furthermore, the place was lightly defended.

The illness seems to have afflicted George III alone however, casting doubt on an hereditary condition. George III’s medical records cast further doubt on the porphyria diagnosis, showing that he was prescribed medicine based on gentian, a plant with deep blue flowers which may turn the urine blue. He seems to have been afflicted with some kind of mental illness, suffering bouts which occurred with increasing severity and for increasing periods of time. At times he would talk until he foamed at the mouth or go into convulsions where pages had to sit on him to keep the King from injuring himself.

The illness seems to have afflicted George III alone however, casting doubt on an hereditary condition. George III’s medical records cast further doubt on the porphyria diagnosis, showing that he was prescribed medicine based on gentian, a plant with deep blue flowers which may turn the urine blue. He seems to have been afflicted with some kind of mental illness, suffering bouts which occurred with increasing severity and for increasing periods of time. At times he would talk until he foamed at the mouth or go into convulsions where pages had to sit on him to keep the King from injuring himself.

D’Estaing sent an ultimatum to British Commander Augustine Prevost on September 16, 1779. He was to surrender the city “To the arms of his Majesty the King of France”, or he would be personally answerable for what was about to happen. It could not have pleased General Benjamin Lincoln or his Patriot allies when d’Estaing added “I have not been able to refuse the army of the United States uniting itself with that of the King. The junction will probably be effected this day. If I have not an answer therefore immediately, you must confer with General Lincoln and me”.

D’Estaing sent an ultimatum to British Commander Augustine Prevost on September 16, 1779. He was to surrender the city “To the arms of his Majesty the King of France”, or he would be personally answerable for what was about to happen. It could not have pleased General Benjamin Lincoln or his Patriot allies when d’Estaing added “I have not been able to refuse the army of the United States uniting itself with that of the King. The junction will probably be effected this day. If I have not an answer therefore immediately, you must confer with General Lincoln and me”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.