As Spring gives way to Summer, kids of all ages exchange school bags for beach bags. Sports practices and homework are over, for now. We grown-ups can enjoy the last hours of the weekday, under the warmth of the sun.

Gone are the days when the warmth of summer brought with it, the horrors of polio. We have no idea how fortunate we are.

In pre-1955 America and around much of the world, Summer was a time of dread. TIME Magazine offered what solace it could, in 1946: “for many a parent who had lived through the nightmare fear of polio, there was some statistical encouragement: in 1916, 25% of polio’s victims died. This year, thanks to early recognition of the disease and improved treatment (iron lungs, physical therapy, etc.) the death rate is down to 5%.”

Polio is as old as antiquity but major outbreaks are all but unknown, until the 20th century. The 1916 outbreak was particularly severe. Nationally, some 6,000 died of the disease that summer. New York City alone suffered 9,000 cases of polio, forcing a city-wide quarantine.

“Polio was a plague. One day you had a headache and an hour later you were paralyzed. How far the virus crept up your spine determined whether you could walk afterward or even breathe. Parents waited fearfully every summer to see if it would strike. One case turned up and then another. The count began to climb. The city closed the swimming pools and we all stayed home, cooped indoors, shunning other children. Summer seemed like winter then.”

Richard Rhodes, A Hole in the World

To make matters worse, the epidemic took place during one of the hottest Summers in memory, the twin threats of heat and disease driving millions to seek relief at nearby lakes, streams and beaches.

On July 1, 1916, twenty-five-year-old Charles Epting Vansant of Philadelphia was vacationing with family, at the Engleside Hotel on the Jersey shore. Just before dinner, Vansant took a swim with a Chesapeake Bay Retriever, who was playing on the beach. Vansant began to shout and bathers thought he was calling to the dog, but shouts soon turned to screams. As lifeguard Alexander Ott and bystander Sheridan Taylor pulled the man to shore, they could see the shark, following.

Charles Vansant’s left thigh was stripped to the bone. He was brought to the Engleside hotel where he bled to death on the front desk.

Despite the incident, beaches remained open all along the Jersey Shore. Sea captains entering the ports of Newark and New York reported numbers of large sharks swarming off the Jersey shore but such reports received little attention.

The next major shark attack occurred five days later, on July 6. Forty-five miles north of Engleside, Essex & Sussex Hotel bell captain Charles Bruder was swimming near the resort town of Spring Lake. Hearing screams, one woman notified lifeguards that a red canoe had capsized, and lay just below the surface. Lifeguards Chris Anderson and George White rowed out to the spot to discover Bruder, legless, with a shark bite to his abdomen. The twenty-seven year old Swiss army veteran bled to death before ever regaining the shore.

Authorities and the press downplayed the first incident. The New York Times reported that Vansant “was badly bitten in the surf … by a fish, presumably a shark.” Pennsylvania State Fish Commissioner and former director of the Philadelphia Aquarium James M. Meehan opined that “Vansant was in the surf playing with a dog and it may be that a small shark had drifted in at high water, and was marooned by the tide. Being unable to move quickly and without food, he had come in to bite the dog and snapped at the man in passing“.

Response to the second incident was altogether different. Newspapers from the Boston Herald to the San Francisco Chronicle ran the story front page, above the fold. The New York Times went all-in: “Shark Kills Bather Off Jersey Beach“.

A trio of scientists from the American Museum of Natural History held a press conference on July 8, declaring a third such incident unlikely. Be that as it may, John Treadwell Nichols, the only ichthyologist among the three, warned swimmers to stay close to shore, and take advantage of netted bathing areas.

Rumors went into high gear, as an armed motorboat claimed to have chased a shark off Spring Creek Beach. Asbury Park Beach was closed after lifeguard Benjamin Everingham claimed to have beaten a 12-footer back, with an oar.

New Jersey resort owners suffered a blizzard of cancellations and a loss of revenue estimated at $5.6 million in 2017 dollars. In some areas, bathing declined by as much as 75%.

Scores of people died in the oppressive heat. Newspapers reported twenty-six fatalities, in Chicago alone. Air conditioning, invented in 1902, would not be widely available until the 1920s. Rural areas had yet to be electrified.

Today, some sharks are known to be capable of living for a time, in fresh water. Bull sharks have been known to travel as much as sixty miles up the Mississippi River. Researchers report that the Neuse River in North Carolina has been home to bull sharks, possibly arrived in pursuit of young dolphins.

That information wasn’t available in 1916.

As the heat wave dragged on, lakes and rivers crowded with bathers from Gary, Indiana to Manchester, New Hampshire. In New Jersey, ocean beaches remained closed with the exception of the 4th Ave. Beach at Asbury Park, enclosed with a steel-wire-mesh fence and patrolled by armed motorboats.

Eleven miles from the ocean, Matawan New Jersey had little to fear, from sharks. Locals sought relief from the heat in Matawan Creek, a brackish water estuary in the Marlboro Township of Monmouth County. With fresh waters flowing from Baker’s Brook down the salinity gradient to the full-salt waters of Keyport Harbor, Matawan Creek seemed more at risk for snapping turtles and snakes, than sharks.

On July 12, several boys including eleven-year-old epileptic Lester Stilwell were swimming near Wykoff Dock when the boys spotted an “old black weather-beaten board or a weathered log.” The boys scattered when that old log turned out to have a dorsal fin, but Lester Stilwell wasn’t fast enough.

Many dismissed the rantings of five naked, hysterical boys, believing that no shark could be this far inland. Twenty-four year old tailor Stanley Fisher came running, knowing that the boy suffered from epilepsy. Arthur Smith and George Burlew joined in the effort, by now clearly a recovery and no longer a rescue. The trio got in a boat and probed with an oar and some poles, but…nothing. They were about to give up the search when Fisher dove in the water. He actually found the boy’s body, and began to swim to shore.

Townspeople lining the creek looked on in horror, as Fisher now came under attack.

Stanley Fisher made it to shore though his right thigh was severely injured, an eighteen-inch chunk of his thigh gone, and an artery severed. The man would bleed to death at Monmouth Hospital, before the day was over.

The Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 claimed a fifth and final victim thirty minutes later, when 12-year old Joseph Dunn of New York city was bitten a half-mile from the Stilwell and Fisher attacks. A savage tug-of war ensued between Dunn’s brother Michael and sixteen-year-old Jeremiah Hourihan, with local attorney Jacob Lefferts jumping into the water, to help. The boy survived but the damage to his left leg, was severe. He wouldn’t be discharged from the hospital, until September 15.

Based on the style of the attacks and glimpses of the shark(s) themselves, the attacks may have been those of Bull sharks, or juvenile Great Whites. Massive shark hunts were carried out all over the east coast, resulting in the death of hundreds of animals. Whether all five attacks were carried out by a single animal or many, remains unclear.

At the time, the story resulted in international hysteria. Now, the tale is all but unknown, but for the people of Matawan. Stanley’s grave sits on a promontory at the Rose Hill Cemetery, overlooking Lester’s grave, below. People still stop from time to time, leaving flowers, toys and other objects. Perhaps they’re paying tribute. A small token of respect. Homage to the courage of those who would jump into the water, in the face of our most primordial fear.

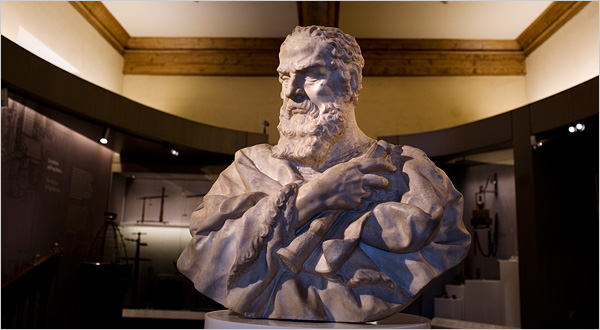

100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day these are the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day these are the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.