At 256 tons with a barrel of 111′ 7″, the “Paris Gun” hurled 38″ shells into the city from a range of 75 miles. If you were in Paris in 1918, you may never have heard of the German “super gun”. You’d have been well acquainted with the damage it caused. You never knew you were under attack until the explosion. The lucky ones were those who lived to see the 4’ deep, 10’-12’ wide crater.

At 256 tons with a barrel of 111′ 7″, the “Paris Gun” hurled 38″ shells into the city from a range of 75 miles. If you were in Paris in 1918, you may never have heard of the German “super gun”. You’d have been well acquainted with the damage it caused. You never knew you were under attack until the explosion. The lucky ones were those who lived to see the 4’ deep, 10’-12’ wide crater.

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. They were said to provide protection for their owners, but only under certain circumstances. You couldn’t make or buy your own, they had to be presented to you. They also had to remain attached, or else the little dolls would lose their protective powers.

These little yarn dolls had names. They were Nénette and Rintintin.

These little yarn dolls had names. They were Nénette and Rintintin.

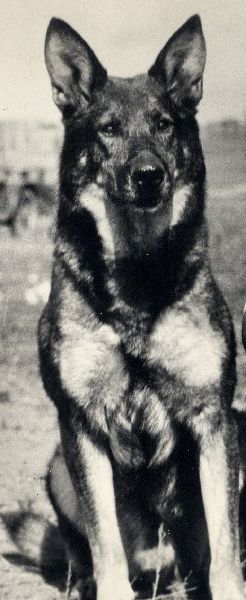

Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. He was aware of the custom, possibly having been given such a talisman himself. In the wake of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Corporal Duncan was sent forward to the small village of Flirey, to check out it’s suitability for an airfield. The place was heavily damaged by shellfire, and Duncan came upon the shattered remains of a dog pound. Once, this kennel had provided Alsatians (German Shepherd Dogs) to the Imperial German Army. Now, the only dogs left alive were a starving mother and five nursing puppies, so young that their eyes were still closed.

Corporal Duncan cared for them, selling several once the puppies were weaned. He sold the mother to an officer and three puppies to fellow soldiers, keeping two for himself. Like those little yarn dolls that French children gave to American soldiers, Duncan felt these two puppies were his good luck charms. He called them Nanette and Rin Tin Tin.

Returning home after the war, Duncan placed the dogs with a police dog breeder and trainer in Long Island. Nanette contracted pneumonia and died, the breeder giving Duncan a female puppy, “Nanette II”, to replace her.

Etzel von Oeringen was born on October 1, 1917 in Germany, coming to America after the Great War and becoming a movie star in the ‘20s. Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel was a German Shepherd Dog, whose appearance in silent films enormously increased the popularity of the breed.

A friend of silent film actor Eugene Pallete, Duncan became convinced that Rin Tin Tin could become the next canine film star. He later wrote, “I was so excited over the motion-picture idea that I found myself thinking of it night and day.”

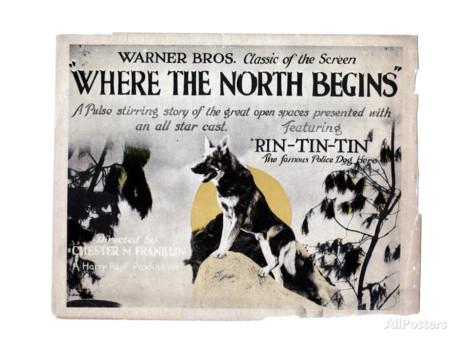

Walking the dog on “Poverty Row”, 1920s slang for B movie studios, did the trick. Rin Tin Tin got his first film break in 1922, replacing a camera shy wolf in “The Man from Hell’s River”. His first starring role in the 1923 “Where the North begins”, is credited with saving Warner Brothers Studios from bankruptcy.

Walking the dog on “Poverty Row”, 1920s slang for B movie studios, did the trick. Rin Tin Tin got his first film break in 1922, replacing a camera shy wolf in “The Man from Hell’s River”. His first starring role in the 1923 “Where the North begins”, is credited with saving Warner Brothers Studios from bankruptcy.

Between-the-scenes silent film “intertitles” were easily changed from one language to another, and Rin Tin Tin films enjoyed international distribution. In 1927, Berlin movie audiences voted him Most Popular Actor.

There’s a Hollywood legend that may or may not be true, that Rin Tin Tin received the most votes for Best Actor at the 1st Academy Awards in 1929. Wishing to appear oh-so serious and wanting a human actor, the Academy threw out the ballots. German actor Emil Jannings got Best Actor on the 2nd ballot.

Rin Tin Tin appeared in 27 feature length silent films, 4 “talkies”, and countless commercials and short films. Regular programming was interrupted to announce his passing on August 10, 1932, at the age of 13. An hour-long program about his life was broadcast the following day.

Rin Tin Tin appeared in 27 feature length silent films, 4 “talkies”, and countless commercials and short films. Regular programming was interrupted to announce his passing on August 10, 1932, at the age of 13. An hour-long program about his life was broadcast the following day.

Suffering from the Great Depression like so many others, Duncan couldn’t afford a fancy funeral. By this time he couldn’t afford the house he lived in. Duncan sold the house and returned the body of his beloved German Shepherd to the country of his birth, where Rin Tin Tin was buried in the Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques, in the Parisian suburb of Asnières-sur-Seine.

Duncan continued breeding the line, careful to preserve the physical qualities and intelligence of the original, avoiding the less desirable traits that crept into other GSD  bloodlines. Rin Tin Tin and Nanette II produced at least 48 puppies. Duncan may have been obsessive about it, at least according to Mrs. Duncan. When she filed for divorce, she named Rin Tin Tin as co-respondent.

bloodlines. Rin Tin Tin and Nanette II produced at least 48 puppies. Duncan may have been obsessive about it, at least according to Mrs. Duncan. When she filed for divorce, she named Rin Tin Tin as co-respondent.

Rin Tin Tin was awarded his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on February 8, 1960. Lee Duncan passed away later that same year. At some point, Duncan had written a poem, a tribute to the companion animal who was no more. If you’ve ever loved a dog, I need not explain his final stanza.

“…A real unselfish love like yours, old pal,

Is something I shall never know again;

And I must always be a better man,

Because you loved me greatly, Rin Tin Tin”.

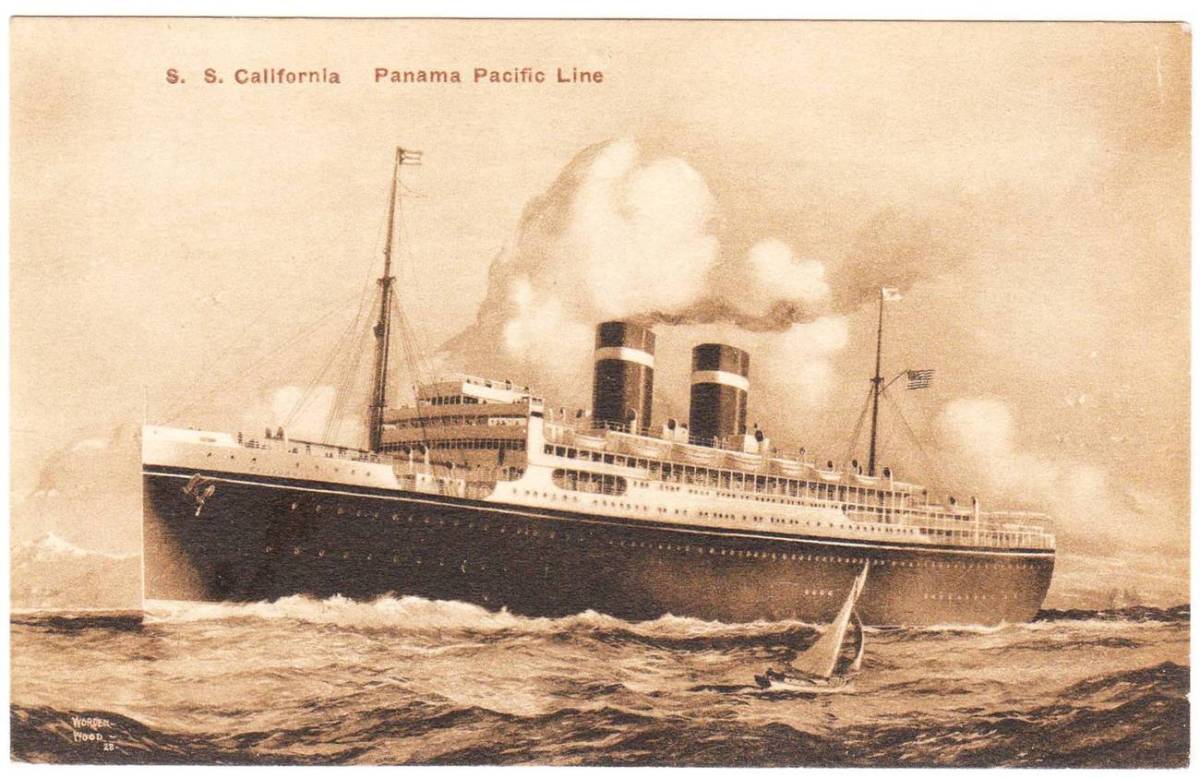

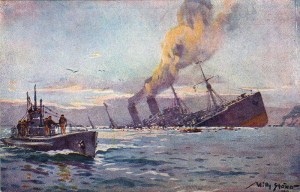

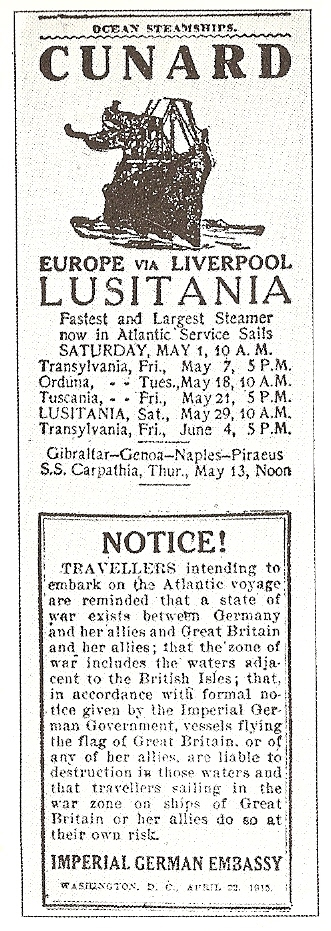

On February 4, 1915, Imperial Germany declared a naval blockade against shipping to Britain, stating that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening”. “Neutral ships” it continued, “will also incur danger in the war region”.

On February 4, 1915, Imperial Germany declared a naval blockade against shipping to Britain, stating that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening”. “Neutral ships” it continued, “will also incur danger in the war region”.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war. The policy was reinstated in January 1917, prompting then-Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to say, “Germany is finished”. He was right.

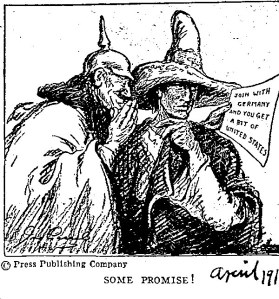

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war. The policy was reinstated in January 1917, prompting then-Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to say, “Germany is finished”. He was right. secretary of the United States Embassy in Britain. This was an overture from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government , promising American territories in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the US.

secretary of the United States Embassy in Britain. This was an overture from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government , promising American territories in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the US.

be related to her previous employment in US Radium’s Orange, New Jersey factory. By that time she was seriously ill, yet Columbia University “Specialist” Frederick Flynn and a “Colleague” pronounced her to be in “fine health”. It was only later that the two were revealed to be company executives.

be related to her previous employment in US Radium’s Orange, New Jersey factory. By that time she was seriously ill, yet Columbia University “Specialist” Frederick Flynn and a “Colleague” pronounced her to be in “fine health”. It was only later that the two were revealed to be company executives. Attorney Raymond Berry filed suit on Fryer’s behalf in 1927, the lawsuit joined by four other dial painters seeking $250,000 apiece in damages. Soon, the newspapers were calling them “radium girls”. The health of all five plaintiffs was deteriorating rapidly, while one stratagem after another was used to delay proceedings. By their first courtroom appearance in January 1928, none could raise their arm to take the oath. Grace Fryer was altogether toothless by this time, unable to walk, requiring a back brace even to sit up.

Attorney Raymond Berry filed suit on Fryer’s behalf in 1927, the lawsuit joined by four other dial painters seeking $250,000 apiece in damages. Soon, the newspapers were calling them “radium girls”. The health of all five plaintiffs was deteriorating rapidly, while one stratagem after another was used to delay proceedings. By their first courtroom appearance in January 1928, none could raise their arm to take the oath. Grace Fryer was altogether toothless by this time, unable to walk, requiring a back brace even to sit up.

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

birth of a son. The Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich. The public was informed of the happy news with a 301 gun salute from the cannons of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Those hopes would be dashed in less than a month, when the infant’s navel began to bleed. It continued to bleed for two days, and took all the doctors at the Tsar’s disposal to stop it.

birth of a son. The Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich. The public was informed of the happy news with a 301 gun salute from the cannons of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Those hopes would be dashed in less than a month, when the infant’s navel began to bleed. It continued to bleed for two days, and took all the doctors at the Tsar’s disposal to stop it. exception. The bleeding episodes suffered by the Tsarevich were often severe, despite his parents never ending attempts to protect him. Doctors’ efforts were frequently in vain, and Alexandra turned to a succession of quacks, mystics and “wise men” for a cure.

exception. The bleeding episodes suffered by the Tsarevich were often severe, despite his parents never ending attempts to protect him. Doctors’ efforts were frequently in vain, and Alexandra turned to a succession of quacks, mystics and “wise men” for a cure. Influential people approached Nicholas and Alexandra with dire warnings, leaving dismayed by their refusal to listen. According to the Royal Couple, Rasputin was the only man who could save their young son Alexei. By 1916 it was clear to many in the nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before the monarchy was destroyed.

Influential people approached Nicholas and Alexandra with dire warnings, leaving dismayed by their refusal to listen. According to the Royal Couple, Rasputin was the only man who could save their young son Alexei. By 1916 it was clear to many in the nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before the monarchy was destroyed. nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia…[I]f it was your relations who have wrought my death…none of your children or relations will remain alive for two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…”

nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia…[I]f it was your relations who have wrought my death…none of your children or relations will remain alive for two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…”

the raiders entered Pretoria on January 2, in chains. The Transvaal government received almost £1 million compensation from the British South Africa Company, turning their prisoners over to be tried by the British government. Jameson was convicted of leading the raid and sentenced to 15 months in prison. During the whole ordeal, he never revealed the degree to which British politicians supported the raid, or the way they betrayed him in the end.

the raiders entered Pretoria on January 2, in chains. The Transvaal government received almost £1 million compensation from the British South Africa Company, turning their prisoners over to be tried by the British government. Jameson was convicted of leading the raid and sentenced to 15 months in prison. During the whole ordeal, he never revealed the degree to which British politicians supported the raid, or the way they betrayed him in the end.

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather later wrote: “I wouldn’t have missed that unique and weird Christmas Day for anything. … I spotted a German officer, some sort of lieutenant I should think, and being a bit of a collector, I intimated to him that I had taken a fancy to some of his buttons. … I brought out my wire clippers and, with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons and put them in my pocket. I then gave him two of mine in exchange. … The last I saw was one of my machine gunners, who was a bit of an amateur hairdresser in civil life, cutting the unnaturally long hair of a docile Boche, who was patiently kneeling on the ground whilst the automatic clippers crept up the back of his neck.”

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather later wrote: “I wouldn’t have missed that unique and weird Christmas Day for anything. … I spotted a German officer, some sort of lieutenant I should think, and being a bit of a collector, I intimated to him that I had taken a fancy to some of his buttons. … I brought out my wire clippers and, with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons and put them in my pocket. I then gave him two of mine in exchange. … The last I saw was one of my machine gunners, who was a bit of an amateur hairdresser in civil life, cutting the unnaturally long hair of a docile Boche, who was patiently kneeling on the ground whilst the automatic clippers crept up the back of his neck.” December 24-25, 1914, lasting in some sectors until New Year’s Day.

December 24-25, 1914, lasting in some sectors until New Year’s Day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.