Several years ago, my brother was working in Washington, part of his work in military aviation. I was passing through, and it was a rare opportunity to spend some time together. There were a few things that we needed to see while we were there. The grave of our father’s father, at Arlington. The Tomb of the Unknown. The memorials to the second world war, and the war in Korea.

And before it was over, we wanted to see the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial.

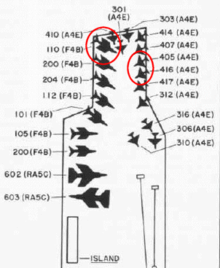

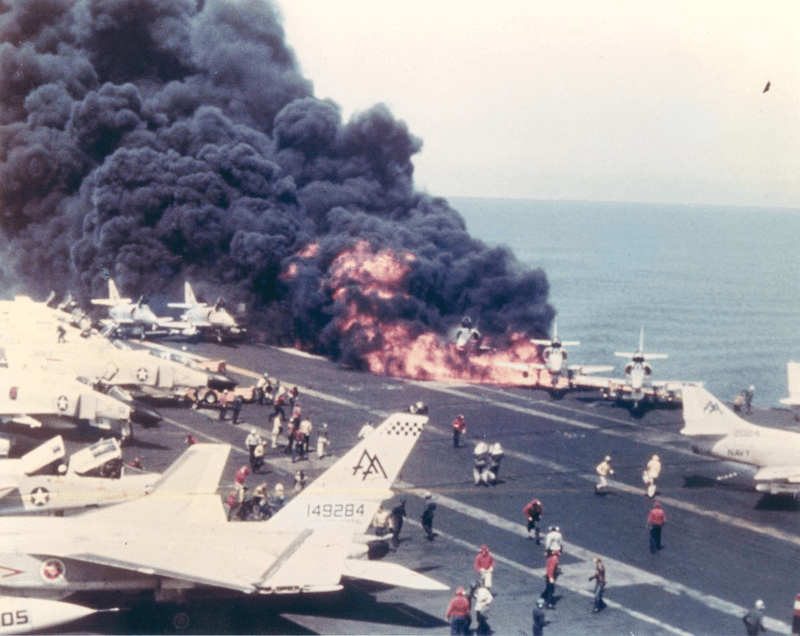

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. Thirty-one years later, we had come to pay a debt of honor to Uncle Gary’s shipmates, the 134 names inscribed on panel 24E, victims of the 1967 disaster aboard the Supercarrier, USS Forrestal.

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. Thirty-one years later, we had come to pay a debt of honor to Uncle Gary’s shipmates, the 134 names inscribed on panel 24E, victims of the 1967 disaster aboard the Supercarrier, USS Forrestal.

We were soon absorbed in the majesty and the solemnity, of the place.

The Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial is a black granite wall, 493½-feet long and 10-feet, 3-inches high at its peak, laid out in a great wedge of stone which seems to rise from the earth and return to it. The name of every person lost in the war in Vietnam is engraved on that wall, appearing in the order in which they were lost.

Go to the highest point of the memorial, panel 1E, the very first name is that of Air Force Tech Sgt. Richard B. Fitzgibbon, Jr., of Stoneham, Massachusetts, killed on June 8, 1956. Some distance to his right you will find the name of Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Richard B. Fitzgibbon III, killed on Sept. 7, 1965. They are one of three Father/Son pairs, so remembered.

The names begin at the center and move outward, the east wing ending on May 25, 1968. The same day continues at the far end of the west wing, moving back toward the center at panel 1W. The last name on the wall, the last person killed in the war, meets the first. The circle is closed.

There, you will find the name of Kelton Rena Turner of Los Angeles, an 18-year old Marine, killed in action on May 15, 1975 in the “Mayaguez incident”, two weeks after the evacuation of Saigon. Most sources list Gary L. Hall, Joseph N. Hargrove and Danny G. Marshall as the last to die in Vietnam, though their fate remains, unknown. These three were United States Marines, an M-60 machine gun squad, mistakenly left behind while covering the evacuation of their comrades, from the beaches of Koh Tang Island. Their names appear along with Turner’s, on panel 1W, lines 130-131.

Left to right: PFC Gary Hall, KIA age 19, LCPL Joseph Hargrove, KIA on his 24th birthday, Pvt Danny Marshall, KIA age 19, PFC Dan Bullock, KIA age 15

There were 57,939 names inscribed on the Memorial when it opened in 1982. 39,996 died at age 22 or younger. 8,283 were 19 years old. The 18-year-olds are the largest age group, with 33,103. Twelve of them were 17, and five were 16. There is one name on panel 23W, line 096, that of PFC Dan Bullock, United States Marine Corps. He was 15 years old on June 7, 1969. The day he died.

Eight names are those of women, killed while nursing the wounded. 997 soldiers were killed on their first day in Vietnam. 1,448 died on their last. There are 31 pairs of brothers on the Wall: 62 parents who lost two of their sons.

As of Memorial Day 2015, there are 58,307, as the names of military personnel who succumbed to wounds sustained during the war, were added to the wall.

Over the years, the Wall has inspired a number of tributes, including a traveling 3/5ths scale model of the original and countless smaller ones, bringing the grandeur of this object to untold numbers without the means or opportunity, to travel to the nation’s capital.

In South Lyons Michigan, the black marble Michigan War Dog Memorial pays tribute to the names and tattoo numbers of 4,234 “War Dogs” who served in Southeast Asia, the vast majority of whom were left behind as “surplus equipment”.

There is even a Vietnam Veterans Dog Tag Memorial, in Chicago.

Eight years ago, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, www.vvmf.org began work on a virtual “Wall of Faces”, where each name is remembered with a face, and a story to go with it. As I write this, the organization is still in need of some 6,000 photographs.

Check it out. Pass it around. You might be able to help.

I was nine years old in May 1968, the single deadliest month of that war, with 2,415 killed. Fifty years later, I still remember the way so many disgraced themselves, by the way they treated those returning home from Vietnam.

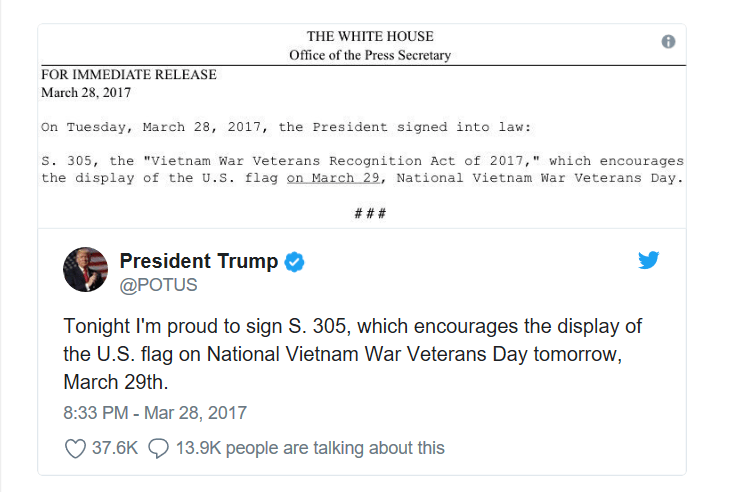

I can only hope that today, veterans of the war in Vietnam have some sense of the appreciation that is their due, the recognition too often denied them, those many years ago. And I trust that my countrymen will remember, if they ever have an issue with United States war policy, they need to take it up with a politician. Not with the Armed Services member who is doing what his country asked him to do.

There had been little contact through the evening of the 7th, when B and C Companies of the 1/503rd took up a night defensive position in the triple canopied jungle near Hill 65.

There had been little contact through the evening of the 7th, when B and C Companies of the 1/503rd took up a night defensive position in the triple canopied jungle near Hill 65. Outnumbered in some places six to one, it was a desperate fight for survival as parts of B and C companies were isolated in shoulder to shoulder, hand to hand fighting.

Outnumbered in some places six to one, it was a desperate fight for survival as parts of B and C companies were isolated in shoulder to shoulder, hand to hand fighting. “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Specialist 5 Joel demonstrated indomitable courage, determination, and professional skill when a numerically superior and well-concealed Viet Cong element launched a vicious attack which wounded or killed nearly every man in the lead squad of the company. After treating the men wounded by the initial burst of gunfire, he bravely moved forward to assist others who were wounded while proceeding to their objective. While moving from man to man, he was struck in the right leg by machine gun fire. Although painfully wounded his desire to aid his fellow soldiers transcended all personal feeling. He bandaged his own wound and self-administered morphine to deaden the pain enabling him to continue his dangerous undertaking. Through this period of time, he constantly shouted words of encouragement to all around him. Then, completely ignoring the warnings of others, and his pain, he continued his search for wounded, exposing himself to hostile fire; and, as bullets dug up the dirt around him, he held plasma bottles high while kneeling completely engrossed in his life saving mission. Then, after being struck a second time and with a bullet lodged in his thigh, he dragged himself over the battlefield and succeeded in treating 13 more men before his medical supplies ran out. Displaying resourcefulness, he saved the life of one man by placing a plastic bag over a severe chest wound to congeal the blood. As 1 of the platoons pursued the Viet Cong, an insurgent force in concealed positions opened fire on the platoon and wounded many more soldiers. With a new stock of medical supplies, Specialist 5 Joel again shouted words of encouragement as he crawled through an intense hail of gunfire to the wounded men. After the 24 hour battle subsided and the Viet Cong dead numbered 410, snipers continued to harass the company. Throughout the long battle, Specialist 5 Joel never lost sight of his mission as a medical aid man and continued to comfort and treat the wounded until his own evacuation was ordered. His meticulous attention to duty saved a large number of

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Specialist 5 Joel demonstrated indomitable courage, determination, and professional skill when a numerically superior and well-concealed Viet Cong element launched a vicious attack which wounded or killed nearly every man in the lead squad of the company. After treating the men wounded by the initial burst of gunfire, he bravely moved forward to assist others who were wounded while proceeding to their objective. While moving from man to man, he was struck in the right leg by machine gun fire. Although painfully wounded his desire to aid his fellow soldiers transcended all personal feeling. He bandaged his own wound and self-administered morphine to deaden the pain enabling him to continue his dangerous undertaking. Through this period of time, he constantly shouted words of encouragement to all around him. Then, completely ignoring the warnings of others, and his pain, he continued his search for wounded, exposing himself to hostile fire; and, as bullets dug up the dirt around him, he held plasma bottles high while kneeling completely engrossed in his life saving mission. Then, after being struck a second time and with a bullet lodged in his thigh, he dragged himself over the battlefield and succeeded in treating 13 more men before his medical supplies ran out. Displaying resourcefulness, he saved the life of one man by placing a plastic bag over a severe chest wound to congeal the blood. As 1 of the platoons pursued the Viet Cong, an insurgent force in concealed positions opened fire on the platoon and wounded many more soldiers. With a new stock of medical supplies, Specialist 5 Joel again shouted words of encouragement as he crawled through an intense hail of gunfire to the wounded men. After the 24 hour battle subsided and the Viet Cong dead numbered 410, snipers continued to harass the company. Throughout the long battle, Specialist 5 Joel never lost sight of his mission as a medical aid man and continued to comfort and treat the wounded until his own evacuation was ordered. His meticulous attention to duty saved a large number of  lives and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all. Specialist 5. Joel’s profound concern for his fellow soldiers, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country“.

lives and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all. Specialist 5. Joel’s profound concern for his fellow soldiers, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country“.

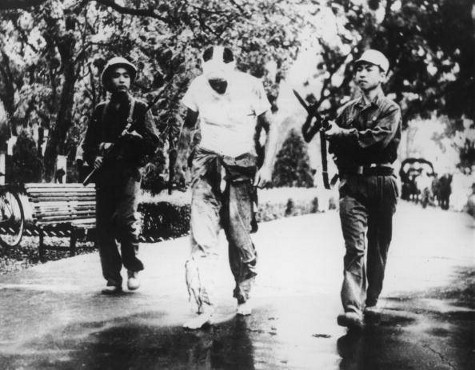

Humbert Roque Versace was born in Honolulu on July 2, 1937, the oldest of five sons born to Colonel Humbert Joseph Versace. Writer Marie Teresa “Tere” Rios was his mother, author of the

Humbert Roque Versace was born in Honolulu on July 2, 1937, the oldest of five sons born to Colonel Humbert Joseph Versace. Writer Marie Teresa “Tere” Rios was his mother, author of the  He did his tour, and voluntarily signed up for another six months. By the end of October 1963, Rocky had fewer than two weeks to the end of his service. He had served a year and one-half in the Republic of Vietnam. Now he planned to go to seminary school. He had already received his acceptance letter, from the Maryknoll order.

He did his tour, and voluntarily signed up for another six months. By the end of October 1963, Rocky had fewer than two weeks to the end of his service. He had served a year and one-half in the Republic of Vietnam. Now he planned to go to seminary school. He had already received his acceptance letter, from the Maryknoll order.

The effect was entirely unacceptable to his Communist tormentors. To the people of these villages, this man made sense.

The effect was entirely unacceptable to his Communist tormentors. To the people of these villages, this man made sense.

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953.

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953. In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

Thorne was soon headed to Special Forces, the elite warrior becoming an instructor of skiing, mountaineering, survival and guerrilla tactics.

Thorne was soon headed to Special Forces, the elite warrior becoming an instructor of skiing, mountaineering, survival and guerrilla tactics. As part of the 10th Special Forces Group, Thorne served in a search-and-rescue capacity in West Germany, earning a reputation for courage in operations to recover bodies and classified documents, following a plane in the Zagros Mountains of Iran.

As part of the 10th Special Forces Group, Thorne served in a search-and-rescue capacity in West Germany, earning a reputation for courage in operations to recover bodies and classified documents, following a plane in the Zagros Mountains of Iran.

Carlos Norman Hathcock, born this day in Little Rock in 1942, was a Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant and sniper with a record of 93 confirmed and greater than 300 unconfirmed kills during the American war in Vietnam.

Carlos Norman Hathcock, born this day in Little Rock in 1942, was a Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant and sniper with a record of 93 confirmed and greater than 300 unconfirmed kills during the American war in Vietnam. The sniper’s choice of target could at times be intensely personal. One female Vietcong sniper, the platoon leader and interrogator called ‘Apache’ due to her interrogation techniques, would torture Marines and ARVN soldiers until they bled to death. Her signature was to cut the eyelids off her victims. After she skinned one Marine alive and left him emasculated within earshot of his base, Hatchcock spent weeks hunting this one sniper.

The sniper’s choice of target could at times be intensely personal. One female Vietcong sniper, the platoon leader and interrogator called ‘Apache’ due to her interrogation techniques, would torture Marines and ARVN soldiers until they bled to death. Her signature was to cut the eyelids off her victims. After she skinned one Marine alive and left him emasculated within earshot of his base, Hatchcock spent weeks hunting this one sniper.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows.

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows. The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence.

The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence. Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue

Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

France would leave the country following defeat by Viet Minh forces at

France would leave the country following defeat by Viet Minh forces at  Richard M. Nixon won overwhelming victory in the Presidential election of 1968, running on a platform including a “secret plan” to end the war in Vietnam.

Richard M. Nixon won overwhelming victory in the Presidential election of 1968, running on a platform including a “secret plan” to end the war in Vietnam. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and other “New Left” organizations staged sit-ins in the fall of 1968. Demonstrations became violent six months later, resulting in 58 arrests. Four SDS leaders spent six months in prison.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and other “New Left” organizations staged sit-ins in the fall of 1968. Demonstrations became violent six months later, resulting in 58 arrests. Four SDS leaders spent six months in prison.

Tear gas failed to break up the crowd and several canisters were thrown back, with near-constant volleys of rocks, bottles and other projectiles. 77 National Guardsmen advanced in line-abreast, as screaming protesters closed behind them. Guardsmen briefly assumed firing positions when cornered near a chain link fence, though no one fired.

Tear gas failed to break up the crowd and several canisters were thrown back, with near-constant volleys of rocks, bottles and other projectiles. 77 National Guardsmen advanced in line-abreast, as screaming protesters closed behind them. Guardsmen briefly assumed firing positions when cornered near a chain link fence, though no one fired.

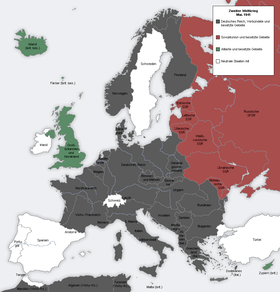

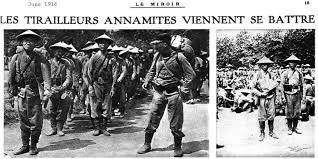

France re-occupied the region following the Japanese defeat ending WWII, but soon faced the same opposition from the army of Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap. What began as a low level rural insurgency, later became a full-scale modern war when Communist China entered the fray in 1949.

France re-occupied the region following the Japanese defeat ending WWII, but soon faced the same opposition from the army of Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap. What began as a low level rural insurgency, later became a full-scale modern war when Communist China entered the fray in 1949. US policy makers feared a “domino” effect, and with good cause. The 15 core nations of the Soviet bloc were soon followed by Eastern Europe, as Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia fell into the Soviet sphere of influence. Germany was partitioned into Communist and free-enterprise spheres after WWII, followed by China, North Korea and on across Southeast Asia.

US policy makers feared a “domino” effect, and with good cause. The 15 core nations of the Soviet bloc were soon followed by Eastern Europe, as Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia fell into the Soviet sphere of influence. Germany was partitioned into Communist and free-enterprise spheres after WWII, followed by China, North Korea and on across Southeast Asia.

Even then it wasn’t over. Communist forces violated cease-fire agreements before they were signed. Some 7,000 US civilian Department of Defense employees stayed behind to aid South Vietnam in conducting an ongoing and ultimately futile war against communist North Vietnam.

Even then it wasn’t over. Communist forces violated cease-fire agreements before they were signed. Some 7,000 US civilian Department of Defense employees stayed behind to aid South Vietnam in conducting an ongoing and ultimately futile war against communist North Vietnam. Imagine feeling so desperate, so fearful of this alien ideology invading your country, that you convert all your worldly possessions and those of your family to a single diamond, bite down on that stone so hard it embedded in your shattered teeth, and fled with your family to open ocean in a small boat. All in the faint and desperate hope, of getting out of that place. That is but one story among more than three million “boat people”. Three million from a combined population of 56 million, fleeing the Communist onslaught in hopes of temporary asylum in other countries in Southeast Asia or China.

Imagine feeling so desperate, so fearful of this alien ideology invading your country, that you convert all your worldly possessions and those of your family to a single diamond, bite down on that stone so hard it embedded in your shattered teeth, and fled with your family to open ocean in a small boat. All in the faint and desperate hope, of getting out of that place. That is but one story among more than three million “boat people”. Three million from a combined population of 56 million, fleeing the Communist onslaught in hopes of temporary asylum in other countries in Southeast Asia or China.

themselves, and came to feel as I do to this day, that anyone who has a problem with our country’s war policy, needs to take it up with a politician. Not with a member of the Armed Services.

themselves, and came to feel as I do to this day, that anyone who has a problem with our country’s war policy, needs to take it up with a politician. Not with a member of the Armed Services.

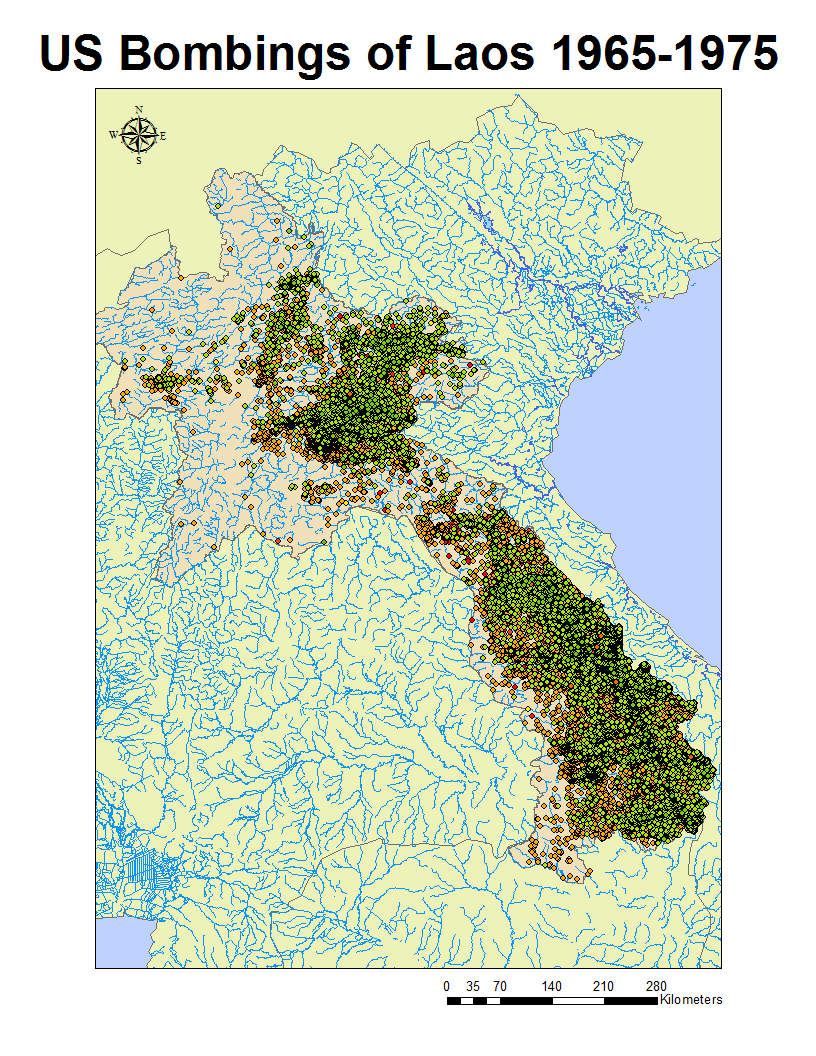

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

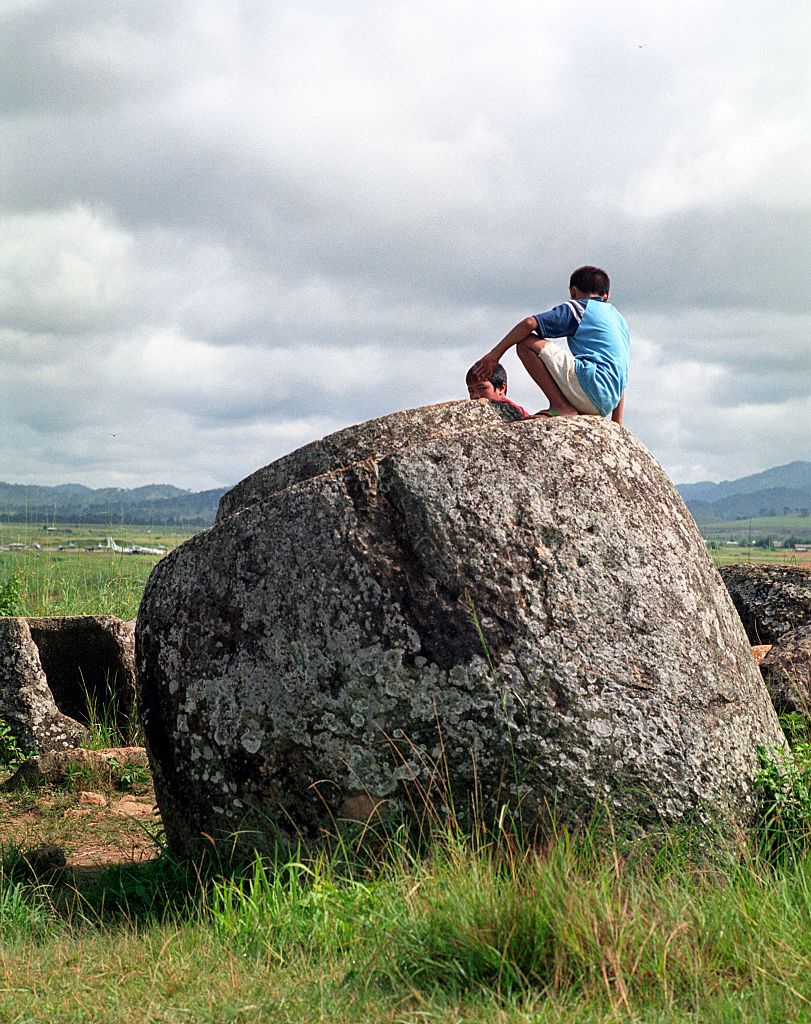

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.