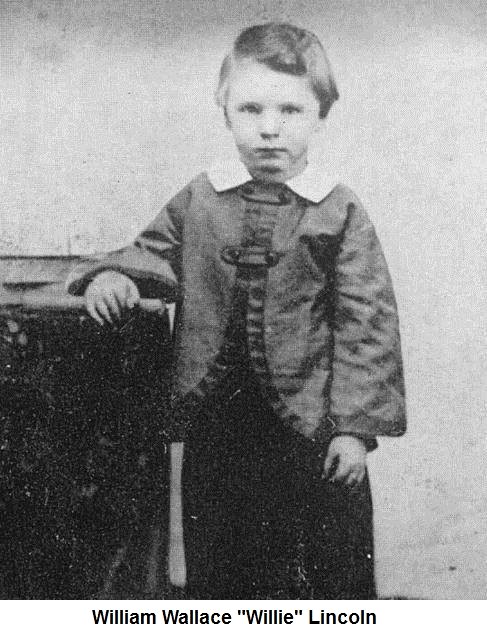

A boy was born on this day in 1892 in the south of Italy, James Vincenzo, the first son of a barber named Gabriele Capone and his wife, Teresa. A second son named Ralph came along before the small family emigrated to the United States in pursuit, of a better life.

Gabriele and Teresa would have seven more children in time: Frank and Alphonse followed by Ermina who sadly died in infancy, followed by John, Albert, Matthew and Mafalda.

Most of the brothers followed a life of petty crime but not Vincenzo, the first-born who would often take the ferry to Staten Island to escape the overcrowded mayhem, of the city.

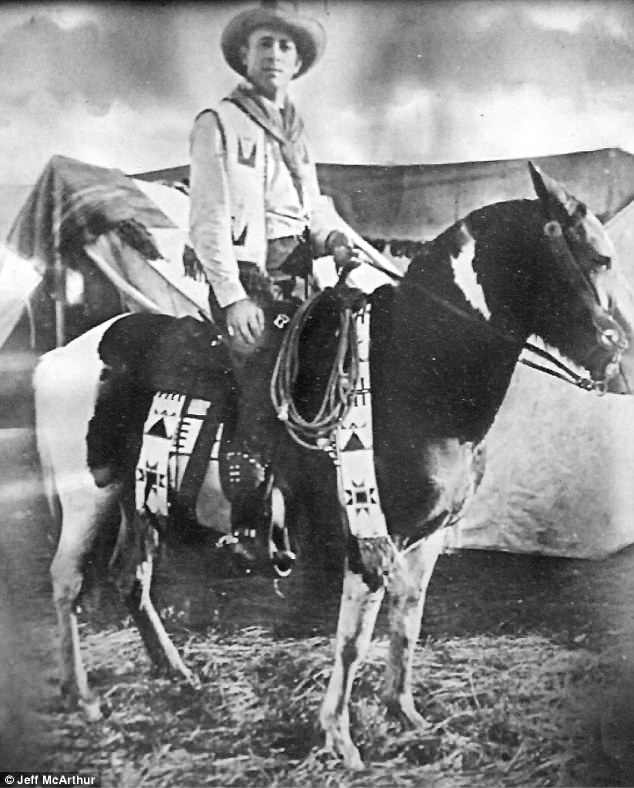

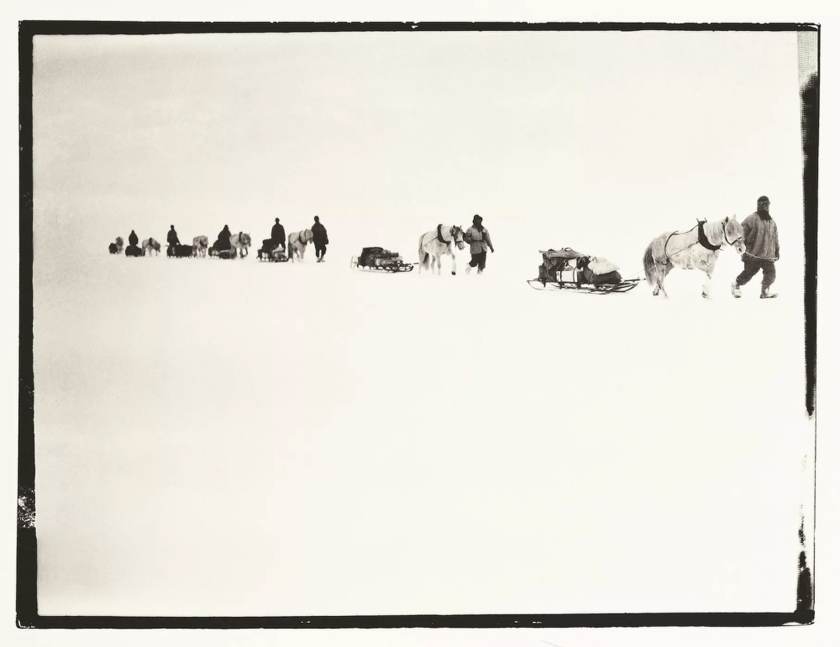

Vincenzo got a job there with help from his father. He was cleaning stables and learning how to care for horses. There he learned to ride and preferred the more “American sounding” part of his name, “James”.

James’ newfound love of horses led to a fascination with Buffalo Bill Cody and the “Wild West” shows, popular at this time. At sixteen he joined the circus, and left the city for good. His family had no idea where he had gone until a letter, about a year later. He was in Kansas he wrote, working as a roustabout with a traveling circus.

This was the age of the silent film, William S. Hart one of the great “cowboy” stars of the era. Hart was larger than life, the six-gun toting cow-punching gunslinger from a bygone era.

The roustabout idolized the silent film star and adopted his mannerisms, complete with low-slung six-shooters, red bandanna and ten-gallon hat. He worked hard to lose his Brooklyn accent and explained his swarthy complexion, explaining he was part native American.

James even adopted the silent film star’s name and enlisted in the Army as Richard James Hart claiming to be a farmer, from Indiana. Some stories will tell you that Hart fought in France and rose to the rank of Lieutenant, in the military police. Others will tell you he joined the American Legion after the war only to be thrown out when it was learned, the whole story was fake.

Be that as it may, Vincenzo legally changed his name to Richard James Hart.

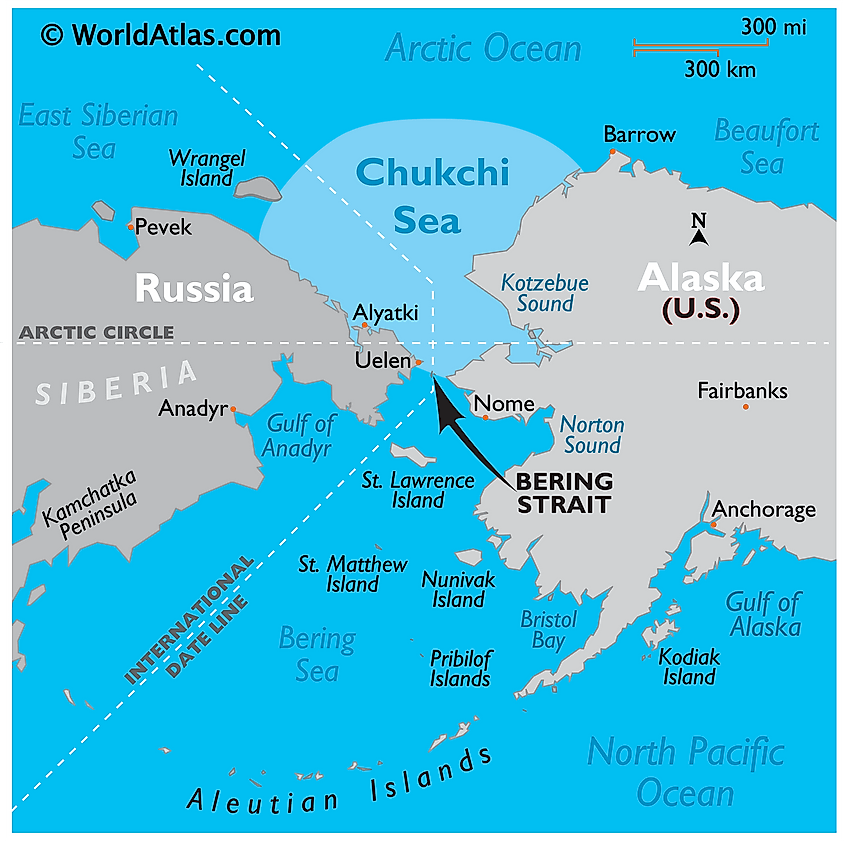

Richard Hart stepped off the freight train in 1919, a walking, talking anachronism. The personification of a 19th century Wild West gunfighter, from his cowboy boots to the embroidered vest to that broad-brimmed Stetson hat. This was Homer Nebraska, a small town of about 500, some seventeen miles from Sioux City Iowa.

He claimed to be a hero of the Great War, personally decorated by General John J. Pershing. Intelligent, ambitious and not the least afraid of hard work, Hart took jobs as paper hanger, house painter, whatever it took.

He was short and powerfully built with the look of a man who carried mixed Indian or Mexican blood, regaling veterans at the local American Legion with tales of his exploits, against the Hun.

The man could fight and he knew how to use those guns, amazing onlookers with feats of marksmanship behind the Legion post.

Any doubts concerning the man’s physical courage were put to rest that May when a flash-flood nearly killed the Winch family of neighboring Emerson, Nebraska. Dashing across the raging flood time after time, two-gun Hart brought the family to safety. Nineteen-year-old Kathleen was so taken with her savior she married him that Fall, a marriage which produced four sons.

The small town was enthralled by this new arrival, the town council appointing Hart as Marshall. He was a big fish in a small pond, elected commander of the Legion post and district commissioner for the Boy Scouts of America.

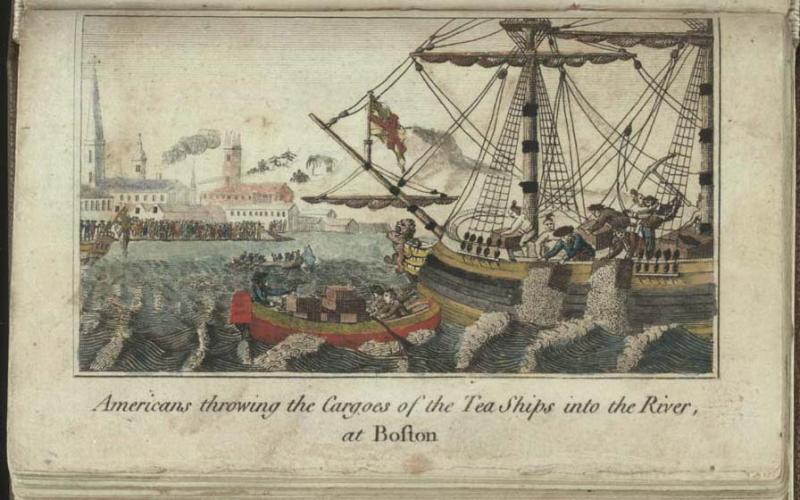

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified on January 16 of that year, the Volstead Act passed by the United States Congress over the veto of President Woodrow Wilson. “Prohibition” was now the law of the land, making it illegal to produce, import, transport or sell intoxicating liquor.

Richard Hart became a prohibition agent in the Summer of 1920 and went immediately to work, destroying stills and arresting area bootleggers.

Hart was loved by temperance types and hated by the “wets”, famous across the state of Nebraska. The Homer Star reported that this hometown hero was “becoming such a menace in the state that his name alone carries terror to the heart of every criminal.”

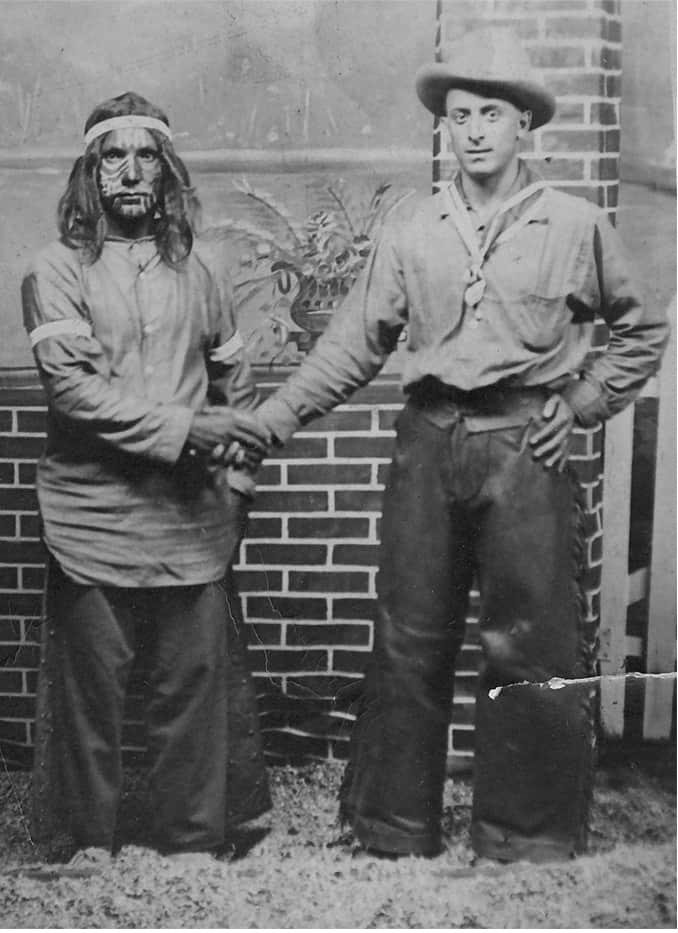

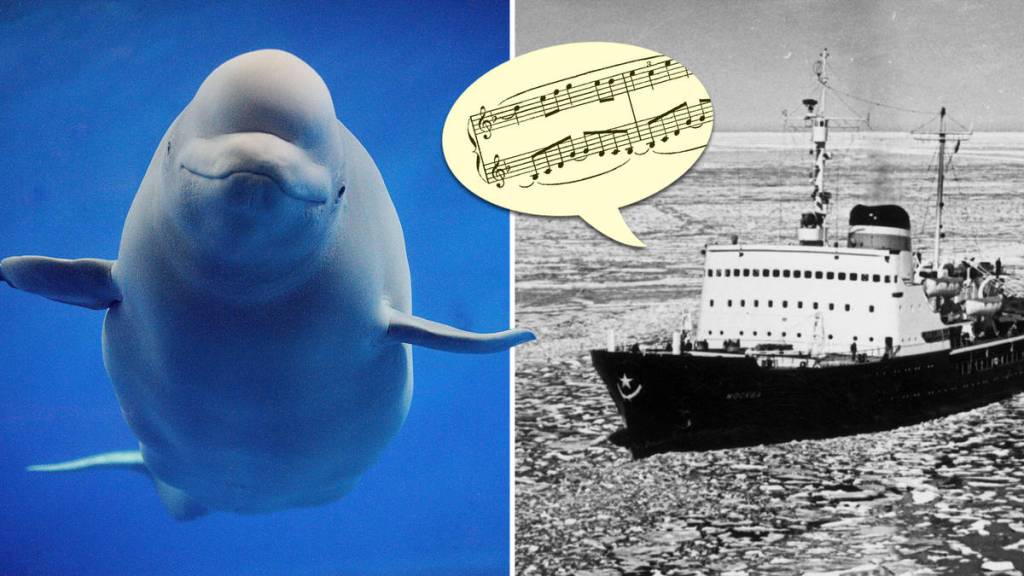

Officials at the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs took note and before long, Hart was performing the more difficult (and dangerous) job of liquor suppression on the reservations.

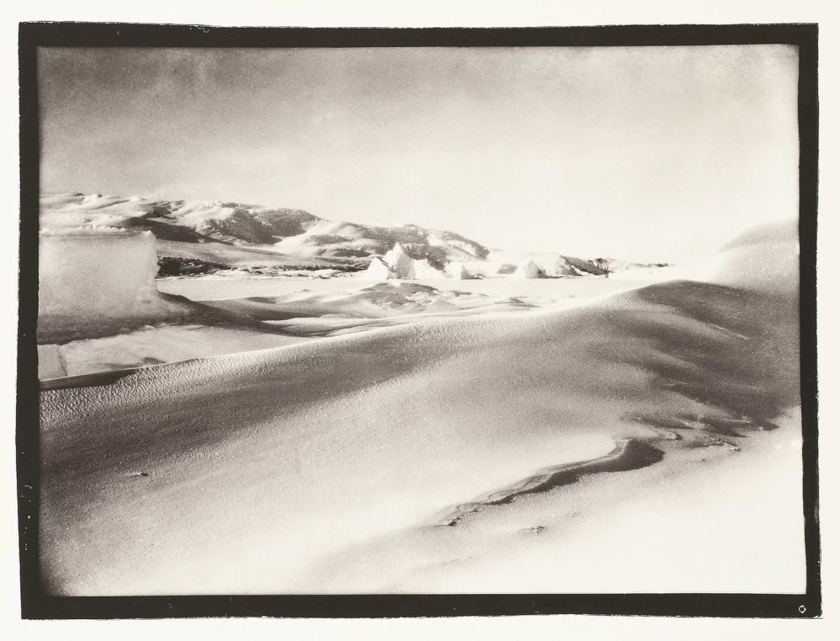

Hart brought his chaps and six-shooters to South Dakota where the Yanktown reservation superintendent reported to his superiors in Washington “I wish to commend Mr. Hart in highest terms for his fearless and untiring efforts to bring these liquor peddlers and moonshiners to justice. …This man Hart is a go-getter.”

Hart became proficient in Lakota and Omaha dialects. Tribal leaders called him “Two Gun”, after the twin revolvers he wore. Some members of the Oglala tribe called him “Soiko”, a name roughly translating as “Big hairy boogey-man”.

By 1927, Two-Guns Hart had achieved such a reputation as to be appointed bodyguard to President Calvin Coolidge, on a trip through the Black Hills of South Dakota.

By 1930, Richard James Hart was so famous a letter addressed only as “Hart” and adorned with a sketch of two pistols, arrived to his attention.

Hart became livestock inspector after repeal of prohibition, and special agent assigned to the Winnebago and Omaha reservations. He was re-appointed Marshall of his adopted home town but, depression-era Nebraska was tough. The money was minuscule and the Marshall was caught, stealing cans of food.

The relatives of one bootlegging victim from his earlier days tracked him down and beat him so severely with brass knuckles, the prohibition cowboy lost the sight of one eye.

Fellow members of the American Legion had by this time contacted the Army, only to learn that Hart’s World War 1 tales were fake. His namesake Richard Jr. went on to lose his life fighting for the nation in World War 2. but Richard himself was never in the Army.

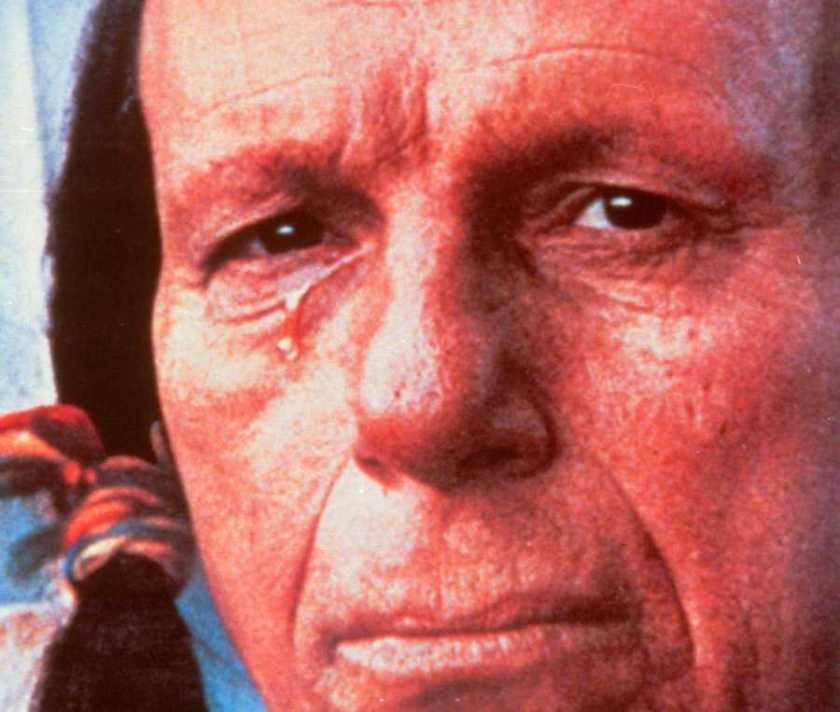

Turns out that other parts of the lawman’s story were phony, too. A good story but altogether fake. Like the Italian-American actor Espera Oscar de Corti better known character “Iron Eyes Cody”, the “crying Indian”, who possessed not a drop of native American blood.

The lawman had left the slums of Brooklyn to become a Prohibition Cowboy while his little brother Alphonse, pursued a life of crime.

You must be logged in to post a comment.