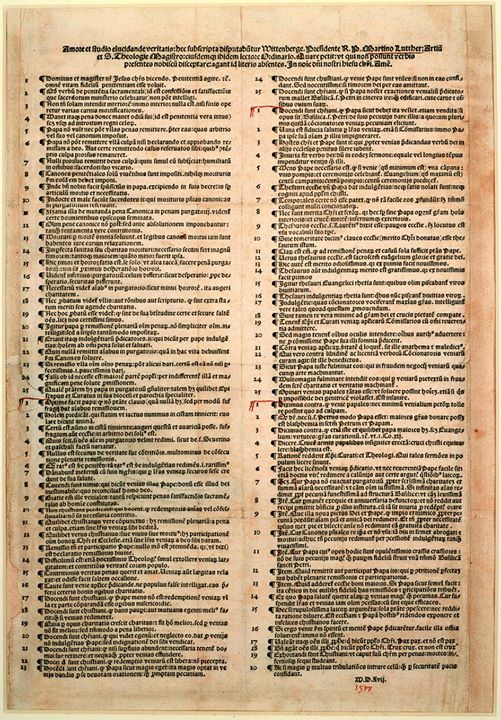

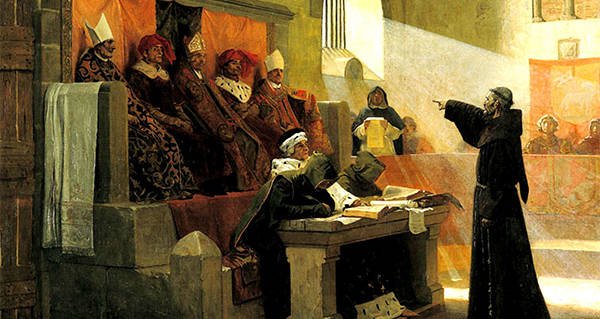

A popular story has Martin Luther nailing a challenge to Church authority to the Wittenberg Palace Church, in 1517. In all probability, it never happened that way. Luther had no intention of confronting the One Church at this time. This was an academic work, mailed to Archbishop Albrecht and offered for scholarly disputation.

Luther’s “95 theses” rocked the Christian world and may be counted among the most important documents in world history, alongside the Cylinder of the Persian King Cyrus, the Magna Carta and the Declaration of independence.

What seems to the modern mind as mere doctrinal differences, were life and death matters in the late middle and early modern ages.

The European “Wars of Religion” spawned by the Protestant Reformation raged across Europe for a hundred years. Other issues were involved as well – territorial ambitions, revolution, Great Power conflicts, but fault lines pulling at the Christian world, were never far from the surface. The Peasant’s War of 1524-’25 alone killed more Europeans than any conflict prior to the French Revolution, in 1789. The Thirty Years’ War of 1618-’48 laid waste to Germany and killed a third of its population, a death rate twice that of World War I.

The Protestant Reformation spread across Europe reaching its greatest geographic extent in the latter half of the 16th century. In England, the schism began with Pope Clement VII and King Henry VIII, of England. Desperate for a male heir, Henry sought divorce from Catherine of Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn. The Pope refused an annulment. Before it was over King Henry VIII had established the church of England with himself, at its head.

Henry died in 1547 leaving his son by Jane Seymour, the nine year old Edward Tudor, King. Next in order of succession came Edward’s half-sister by Catherine of Aragon Mary Tudor, followed by his half-sister Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn.

Despite breaking with the church in Rome, Henry never permitted the renunciation of Catholic doctrine, or ceremony. Henry, the first English monarch raised as a Protestant, dispensed with clerical celibacy and the Mass, and required services to be conducted, in English.

Despite her title, Henry’s cousin Jane had little use for the goings on at the royal court. “Lady” Jane Grey would rather read a book. Pretty, smart and well educated, she was the daughter of Henry’s younger sister and as such, in line for the crown.

At nine Jane was sent to live with Henry’s widow, Katherine Parr.

There exists among us a type of person, with an insatiable need to control the lives of others. People who desire power, above all things. Call it a personality defect or a psychological condition, that’s up to you, but one thing is certain. History is replete with such individuals at all times and in all political stations. All too often, these are the people who Become, history.

Books have been written about the scheming, the grasping for power behind the scenes, of the royal throne. Such machinations are beyond the scope of this essay but this story is chock full of such individuals, not the least of whom were John Dudley, duke of Northumberland and Jane’s own father, Henry.

In 1551, Henry Grey was created 1st duke of Suffolk. With pre-teen Henry on the throne Dudley, duke of Northumberland, exercised enormous power behind the scenes. In May 1553, Suffolk and Dudley arrange of their two children: Lady Jane to Northumberland’s son, Lord Guildford Dudley.

Edward ruled until the ripe old age of fifteen and fell ill from some lung condition, possibly tuberculosis. Knowing he was dying, Edward and his council drew up a “Devise for the Succession” to prevent the return of Catholic rule.

Lady Jane was devoutly Protestant. Edward bypassed his half sisters Mary and Elizabeth to name Jane Grey, his rightful heir. At fifteen, this quiet teenage girl who’d rather read a book became the Great Hope of Protestant England.

King Edward VI died on July 6, 1553 his death kept quiet, for four days. Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed Queen of England, France and Ireland on July 10, her husband Guildford, the Duke of Clarence. Jane fainted on learning she was Queen. She later said she accepted the crown, only with reluctance.

To the devoutly Catholic Mary Tudor, the future “Bloody Mary”, the line of succession was clear. She herself was named in the Parliamentary act of 1544. She was next according to Henry’s private papers. Mary Tudor was not about to be denied what was rightfully hers.

It is said that success has many fathers but failure, is an orphan. Dudley set out with a body of troops, to capture the would be Queen as the privy council, personal advisors to the crown, now declared support for Mary. With the rug pulled out from under him Dudley’s support, evaporated. Even Henry Grey, Jane’s father, switched his support to Mary.

Queen for only nine days, Jane was deposed on July, 19, 1553. The only English monarch in 500 years without so much, as a portrait. Now simply “Jane Dudley, wife of Guildford”, she was imprisoned in the Gaoler’s (Jailer’s) apartments at the Tower of London, Guildford in the Beauchamp Tower.

Mary rode triumphantly into London on August 3, accompanied by her half sister Elizabeth and a procession of over 800 dignitaries.

Jane was charged with high treason as was Guildford and several associates. The trial began on November 3 with no doubt, as to how it would end. Just turned 17 in October the “nine days’ Queen” was convicted of high treason and sentenced to “be burned alive on Tower Hill or beheaded as the Queen pleases”.

Even yet, there was reason to believe that Jane might be spared. What happened next sealed the teenager’s fate.

Once crowned, Mary I wasn’t about to be succeeded by her younger (Protestant) half sister, Elizabeth. She turned her attention to finding a mate. Mary needed to produce an heir. The House of commons petitioned that the new Queen select an English mate, but she chose Prince Philip of Spain.

The marriage was controversial. English patriots opposed the match, not wanting Britain relegated to a mere dependency, of the Habsburgs. English Protestants feared Catholic rule.

There followed a series of uprisings in opposition to the marriage, called after the rebel politician Thomas Wyatt. The so-called Wyatt’s Rebellion explicitly opposed the marriage but carried with it the implication, of an intent to overthrow the Queen. There were even dark rumors, of assassination.

Jane’s father joined in the rebellion as did two of his brothers. For the government, this was the last straw. The Bishop of Winchester persuaded the Queen that Jane was a risk and would continue to be so, due to her influence over Protestant rebels. Her execution and that of her husband were scheduled for February 9.

Three days were allowed for the former Queen to save her life, and convert to Catholicism. Mary even sent her chaplain John Feckenham to “save her soul”.

Jane politely declined to convert but she soon made friends, with Feckenham. She even invited him to her own execution.

On the morning of February 12, 1554, Jane watched out the window as her husband, was wheeled off in a cart. With the words “Oh Guildford” she watched the return of his body and his head, each wrapped in separate white sheets.

Then came the sound of footsteps. At her door.

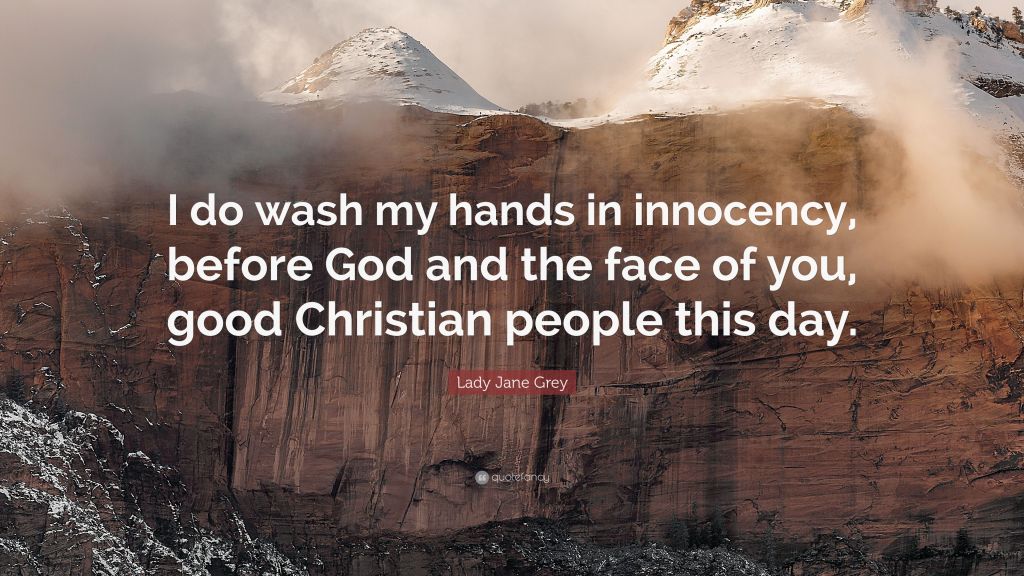

Brought to the scaffold, Jane began to speak. “Good people, I am come hither to die” concluding, “I do wash my hands thereof in innocence“. The law made her a traitor but all she had done, was accept the positi0n.

She recited Psalm 51 (Have mercy upon me, O God) in English and handed her gloves and handkerchief to her maid. As was customary the executioner asked for forgiveness. That she gave, adding “I pray you dispatch me quickly.” She then asked “Will you take it off before I lay me down?” She was referring to her head. “No Madame”, came the reply. Lady Jane applied her own mask and reached out groping, for the block. In that she received help. Outstretching her arms, she spoke. Jesus’ last words, as recounted by Luke: “Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit.”

The slender neck was parted, with a stroke.

There was no funeral. No stone to mark the grave. Lady Jane was simply buried, along with her husband in the parish church of the Tower of London. Saint Peter ad Vincula. (“St. Peter in chains”). She is the last of five beheaded females buried in the chancel area, along with Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Katherine Howard, Lady Rochford and Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury.

Three hundred years later the essayist Thomas Babington wrote in memoriam, of those who rest, at St. Peter ad Vincula:

“In truth there is no sadder spot on the earth than that little cemetery. Death is there associated, not, as in Westminster Abbey and Saint Paul’s, with genius and virtue…but with whatever is darkest in human nature and in human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame…”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.