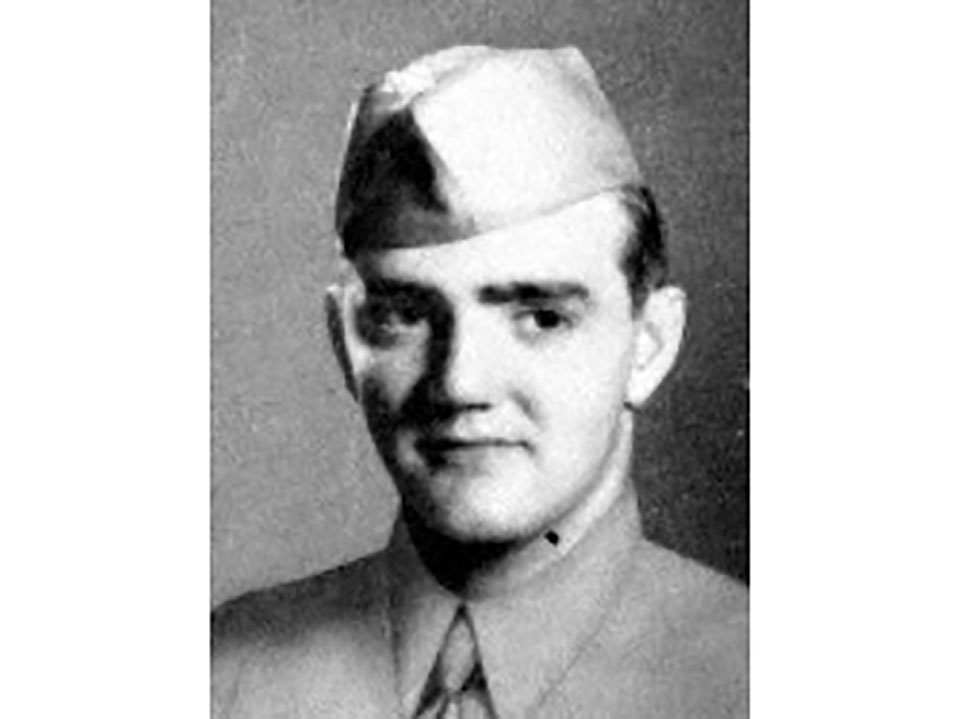

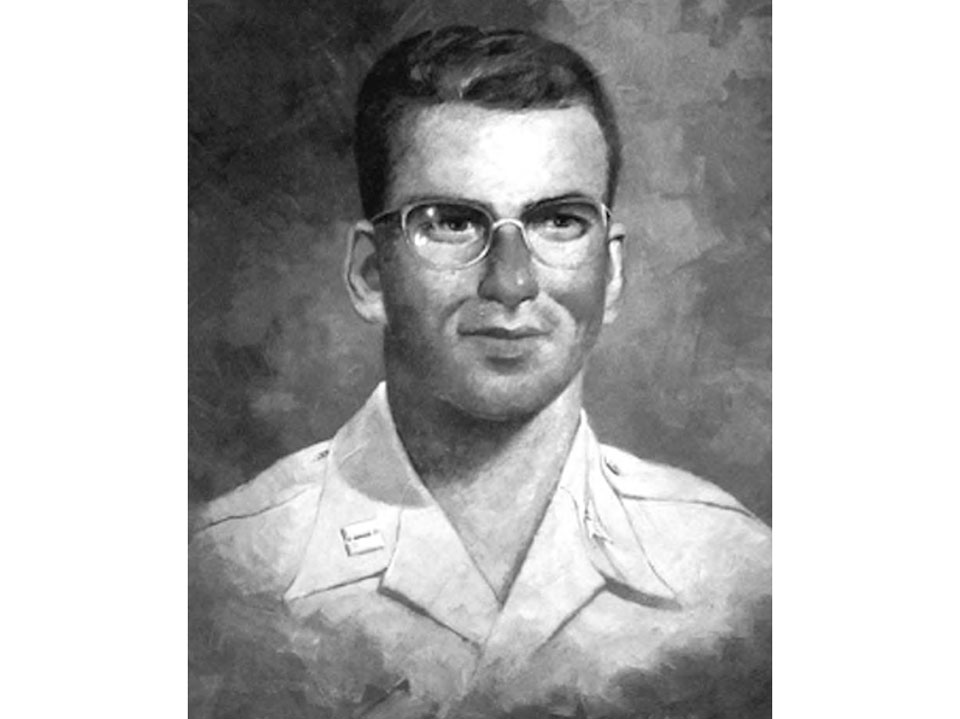

Humbert Roque Versace was born in Honolulu on July 2, 1937, the oldest of five sons born to Colonel Humbert Joseph Versace. Writer Marie Teresa “Tere” Rios was his mother, author of the Fifteenth Pelican. If you don’t recall the book, perhaps you remember the 1960s TV series, based on the story. It was called The Flying Nun.

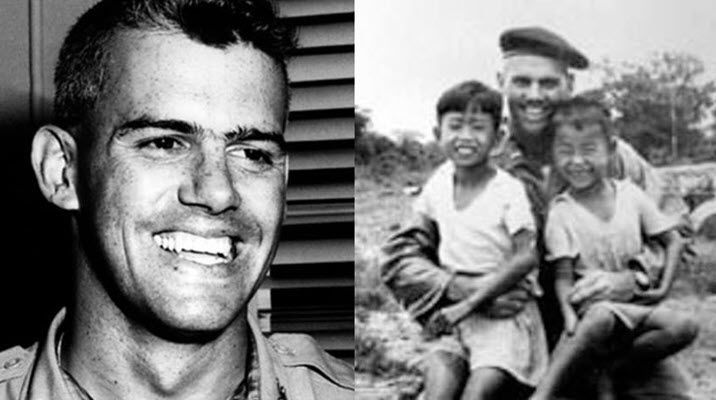

Like his father before him, Humbert, (“Rocky” to his friends), joined the armed services out of high school, graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point, in 1959.

Rocky earned his Ranger tab and parachutist badge the same year, later serving as tank commander with the 1st Cavalry in South Korea, then with the 3rd US Infantry – the “Old Guard”.

Rocky attended the Military Assistance Institute, the Intelligence course at Fort Holabird Maryland, and the USACS Vietnamese language Course at the Presidio of Monterey, beginning his first tour of duty in Vietnam on May 12, 1962.

He did his tour, and voluntarily signed up for another six months. By the end of October 1963, Rocky had fewer than two weeks to the end of his service. He had served a year and one-half in the Republic of Vietnam. Now he planned to go to seminary school. He had already received his acceptance letter, from the Maryknoll order.

Rocky planned to become a Priest of the Roman Catholic faith, and return to the country to help the orphaned children of Vietnam.

His was a bright and shining future. One never meant to be.

Rocky was assisting a Civilian Irregular Defense (CIDG) force of South Vietnamese troops remove a Viet Cong (VC) command post in the Mekong Delta. It was unusual that anyone would volunteer for such a mission, particularly one with his “short-timer’s stick”. This was a daring mission in a very dangerous place.

On October 29, an overwhelming force of Viet Cong ambushed and overran Rocky’s unit. Under siege and suffering multiple bullet and shrapnel wounds, Versace put down suppressing fire, permitting his unit to withdraw from the kill zone.

Another force of some 200 South Vietnamese arrived, too late to alter the outcome. Communist radio frequency jamming had knocked out both main and backup radio channels.

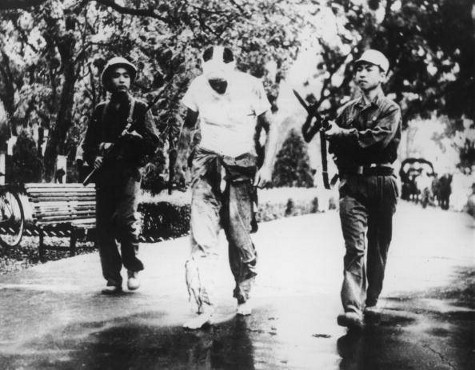

Their position overrun, Captain Versace, Lieutenant Nick Rowe and Sergeant Dan Pitzer were captured and taken to a North Vietnamese prison, deep in the jungle.

For most of the following two years, a 2’x3’x6’ bamboo cage would be their home. On nights when their netting was taken away, the mosquitoes were so thick on their shackled feet, it looked like they were wearing socks.

Years later, President George W. Bush would tell a story, about how Steve Versace described his brother. “If he thought he was right”, Steve said to audience laughter, “he was a pain in the neck. If he knew he was right, he was absolutely atrocious.”

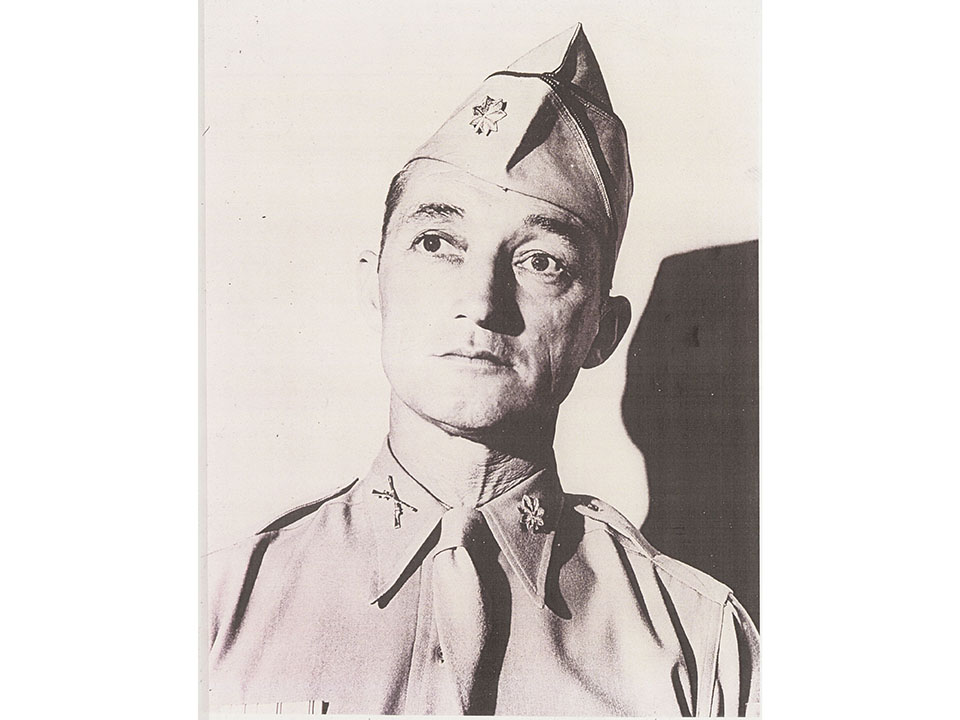

In 1964, Vietnamese interrogators were learning what Steve Versace could have told them, if only they’d asked. His brother could not be broken. Rocky attempted to escape four times, despite leg wounds which left him no option but to crawl on his belly. Each such attempt earned him savage beatings, but that only made him try harder.

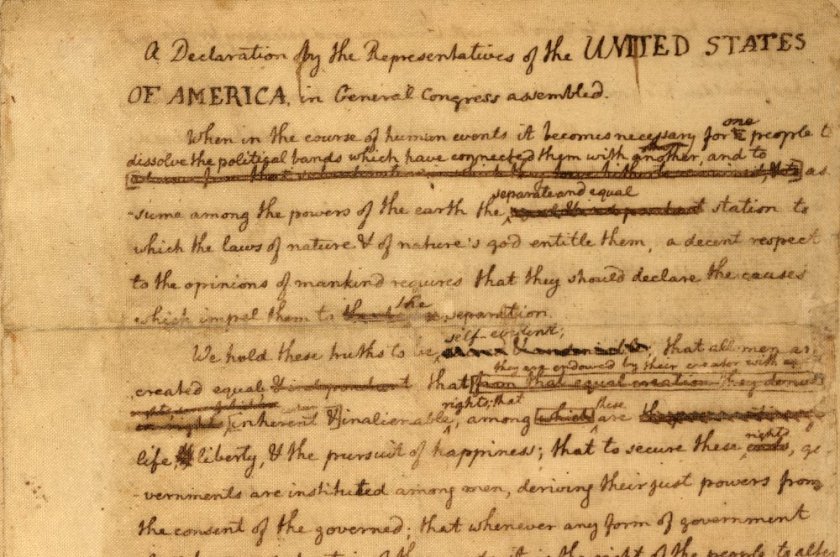

Fluent in French, Vietnamese and English, Rocky could quote chapter and verse from the Geneva Conventions and never quit doing so. He would insult and ridicule his captors in three languages, even as they beat him to within an inch of his life.

Incessant torture and repeated isolation in solitary confinement did nothing to shut him up. Communist indoctrination sessions had to be brought to a halt in French and Vietnamese, because none of his interrogators could effectively argue with this guy. They certainly didn’t want villagers to hear him blow up their Communist propaganda in their own language.

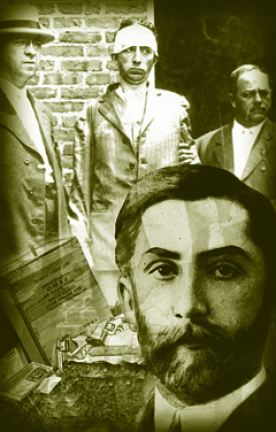

For five months in 1964, reports came back through intelligence circles, of one particular prisoner. Paraded in chains before local villagers, with hair turned snow white and face swollen and yellowed with jaundice. With hands tied behind his back and a rope around his neck, even then this man still spoke in three languages, of God, and Freedom, and American democracy.

The affect was unacceptable to his Communist tormentors. To the people of these villages, this man made sense.

In the end, Versace was isolated from the rest of the prison population, as a dangerous influence. He responded by singing at the top of his lungs, the lyrics of popular songs of the day replaced by messages of inspiration to his fellow POWs. Rocky was last heard belting out “God Bless America”, at the top of his lungs.

Humbert Roque Versace was murdered by his North Vietnamese captors, his “execution” announced on North Vietnamese “Liberation Radio” on September 26, 1965. He was twenty-eight years old.

Rocky’s remains were never recovered. The headstone bearing his name in the Memorial section MG-108 at Arlington National Cemetery, stands over an empty grave. The memory of his name is inscribed on the Courts of the Missing in the Honolulu Memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, and on Panel 1E, line 33, of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

This American hero of Italian and Puerto Rican heritage was nominated for the medal of honor in 1969, an effort culminating in a posthumous Silver Star. In 2002, the Defense Authorization Act approved by the United States Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush, awarded Versace the Medal of Honor.

In a July 8, 2002 ceremony in the East Room of the White House, the President of the United States awarded the Medal of Honor to United States Army Captain Humbert Roque “Rocky” Versace. Dr. Stephen Versace stood in to receive the award, on behalf of his brother. Never before had the nation’s highest honor for military valor been bestowed on a POW, for courage in the face of captivity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.