From the World Cup to the Superbowl, the world of professional sports has little to compare with the race for the Pinnacle Trophy. The contest for Championship, in which entire economies slow to a crawl and even casual sports fans are caught up in the spectacle.

For professional baseball, the “Fall Classic” began in 1903, a best-of-nine “World Series” played out between the Boston Braves and the Pittsburg Pirates. (Boston won, in eight).

Excepting the boycott year of 1904 when there was no series at all, most World Series have been ‘best-of-seven”. That changed in 1919, when league owners agreed to play a nine-game series, to generate more revenue and increase the popularity of the sport.

Today, top players are paid the GDP of developing nations, but that wasn’t always the case. One-hundred years ago, much of that revenue failed to find its way to the players. Even the best, held second jobs.

Around that time, Chicago White Sox owner Chuck Comiskey built the most powerful organizations in professional baseball, despite a stingy reputation.

The scandal of the 1919 “Black Sox” series began when Arnold “Chick” Gandil, the first baseman with ties to Chicago gangsters, convinced his buddy and professional gambler Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, that he could throw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. New York gangster Arnold Rothstein supplied the money through his right-hand man, former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell.

The scandal of the 1919 “Black Sox” series began when Arnold “Chick” Gandil, the first baseman with ties to Chicago gangsters, convinced his buddy and professional gambler Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, that he could throw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. New York gangster Arnold Rothstein supplied the money through his right-hand man, former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams were principally involved with throwing the series, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver attended a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the 1919 post-season.

Star outfielder “Shoeless” Joe Jackson may have been a participant, though his involvement has been disputed. It seems that other players may have used his name in order to give themselves credibility. Utility infielder Fred McMullin was not involved in the planning, but he threatened to report the others unless they cut him in on the payoff.

The more “straight arrow” players on the club knew nothing about the fix. Second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, and pitcher Red Faber had nothing to do with it, though the conspiracy received an unexpected boost, when Faber came down with the flu.

Rumors were flying as the series started on October 2. So much money was bet on Cincinnati, that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Cicotte, who had shrewdly collected his $10,000 the night before, struck leadoff hitter Morrie Rath with his second pitch, a prearranged signal that “the fix was in”.

The plot began to unravel, that first night. Attell withheld the next installment of $20,000, to bet on the following game.

Game 2 starting pitcher Lefty Williams was still willing to go through with the fix, even though he hadn’t been paid. He’d go on to lose his three games in the best-of nine series, but by game 8, he wanted out.

The wheels came off in game three. Former Tigers pitcher and Rothstein intermediary Bill “Sleepy” Burns bet everything he had on Cincinnati, knowing the outcome in advance. Except, Rookie pitcher Dickie Kerr wasn’t in on the fix. He pitched a masterful game in game three, shutting Cincinnati out 3-0, and leaving Burns flat broke.

Cicotte became angry in game 7, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege on their deal. The knuckle baller bore down to a White Sox win and the series stood, 4-3.

Williams was back on the mound in game 8. By this time he wanted out of the deal, but gangsters threatened to hurt him and his family if he didn’t lose the game. Williams threw nothing but mediocre fastballs, allowing four hits and three runs in the first. The White Sox went on to lose that Game 10-5, ending the series in a 3 – 5 Cincinnati win.

Rumors of the fix began immediately, and dogged the team throughout the 1920 season. Chicago Herald and Examiner baseball writer Hugh Fullerton, wrote that there should never be another World Series. A grand jury was convened that September. Two players, Eddie Cicotte and Shoeless Joe Jackson, testified on September 28, both confessing to participating in the scheme. Despite a virtual tie for first place at that time, Comiskey pulled the seven players then in the majors. Gandil was back in the minors, at the time.

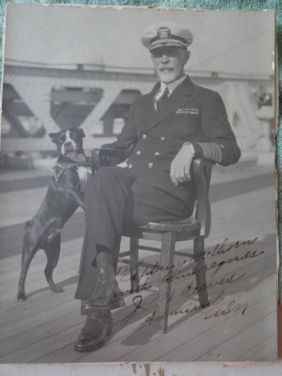

The reputation of professional baseball had suffered a major blow. Franchise owners appointed a man with the best “baseball name” in history, to help straighten out the mess. He was Major League Baseball’s first Commissioner, federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

The Black Sox trial began this day in 1921, in the Criminal Court in Cook County. Key evidence went missing before the trial, including both Cicotte’s and Jackson’s signed confessions. Both recanted and, in the end, all players were acquitted. The missing confessions reappeared several years later, in the possession of Comiskey’s lawyer. It’s funny how that works.

in the possession of Comiskey’s lawyer. It’s funny how that works.

According to legend, a young boy approached Shoeless Joe Jackson one day as he came out of the courthouse. “Say it ain’t so, Joe”. There was no response.

The Commissioner was unforgiving, irrespective of the verdict. The day after the acquittal, Landis issued a statement: “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ball game, no player who undertakes or promises to throw a ball game, no player who sits in confidence with a bunch of crooked ballplayers and gamblers, where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball”.

Jackson, Cicotte, Gandil, Felsch, Weaver, Williams, Risberg, and McMullin are long dead now, but every one remains Banned from Baseball.

Ironically, the 1919 scandal lead the way to the “Curse of the Black Sox”, a World Series championship drought lasting 88 years and ending only in 2005, with a White Sox sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

The Philadelphia Bulletin newspaper published a poem back on opening day for the 1919 series. They would probably have taken it back, if only they could.

“Still, it really doesn’t matter, After all, who wins the flag.

Good clean sport is what we’re after, And we aim to make our brag.

To each near or distant nation, Whereon shines the sporting sun.

That of all our games gymnastic, Base ball is the cleanest one!”

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

In 18th century London, it was a bad idea to go out at night. Not without a lantern in one hand, and a club in the other.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

When the Great Depression descended across the land, minor league clubs folded by the bushel. Small town owners were desperate to innovate. The first-ever night game in professional baseball was played on May 2, 1930, when Des Moines, Iowa hosted Wichita for a Western League game.

In 1912, the Doves adopted an official name of their own. National League franchise owner James Gaffney was a member of Tammany Hall, the political machine that ruled New York, between 1789 and 1967. Tammany Hall’s symbol was an Indian chief, its headquarters called a “wigwam”. So it was that, the oldest franchise in major league baseball, came to be called “the Braves”.

In 1912, the Doves adopted an official name of their own. National League franchise owner James Gaffney was a member of Tammany Hall, the political machine that ruled New York, between 1789 and 1967. Tammany Hall’s symbol was an Indian chief, its headquarters called a “wigwam”. So it was that, the oldest franchise in major league baseball, came to be called “the Braves”.

1915 ushered in a 20-year losing streak for the Braves. Ironically, it was Babe Ruth who was expected to pull it all together, when Braves President Emil Fuchs brought the Bambino back to Boston in 1935.

1915 ushered in a 20-year losing streak for the Braves. Ironically, it was Babe Ruth who was expected to pull it all together, when Braves President Emil Fuchs brought the Bambino back to Boston in 1935.

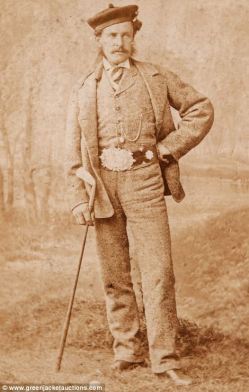

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had died in childbirth.

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had died in childbirth.

Spitballs lessened the natural friction with a pitcher’s fingers, reducing backspin and causing the ball to drop. Sandpapered, cut or scarred balls tended to “break” to the side of the scuff mark.

Spitballs lessened the natural friction with a pitcher’s fingers, reducing backspin and causing the ball to drop. Sandpapered, cut or scarred balls tended to “break” to the side of the scuff mark. Submarine pitches are not to be confused with the windmill underhand pitches we see in softball. Submarine pitchers throw side-arm to under-handed, their upper bodies so low that some of them scuff their knuckles on the ground, the ball rising as it approaches the strike zone.

Submarine pitches are not to be confused with the windmill underhand pitches we see in softball. Submarine pitchers throw side-arm to under-handed, their upper bodies so low that some of them scuff their knuckles on the ground, the ball rising as it approaches the strike zone. 29-year-old Ray Chapman had said this was his last year playing ball. He wanted to spend more time in the family business he had just married into. The man was right. Raymond Johnson Chapman died 12 hours later, the only player in the history of Major League Baseball, to die from injuries sustained during a game.

29-year-old Ray Chapman had said this was his last year playing ball. He wanted to spend more time in the family business he had just married into. The man was right. Raymond Johnson Chapman died 12 hours later, the only player in the history of Major League Baseball, to die from injuries sustained during a game.

In a world where classified government information is kept on personal email servers, there are still some secrets so pinky-swear-double-probation-secret that the truth may Never be known. Among them Facebook “Community Standards” algorithms, the formula for Coca Cola, and the secret fishing hole where Lena Blackburne’s Baseball Rubbing Mud comes from.

In a world where classified government information is kept on personal email servers, there are still some secrets so pinky-swear-double-probation-secret that the truth may Never be known. Among them Facebook “Community Standards” algorithms, the formula for Coca Cola, and the secret fishing hole where Lena Blackburne’s Baseball Rubbing Mud comes from.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

Oh, for the days when the government pretended to look out for our money.

Oh, for the days when the government pretended to look out for our money.

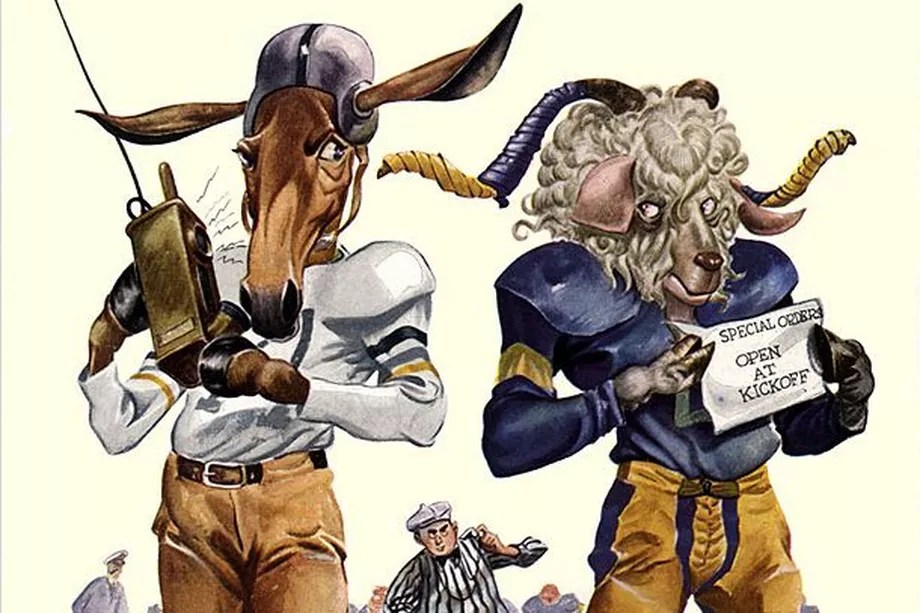

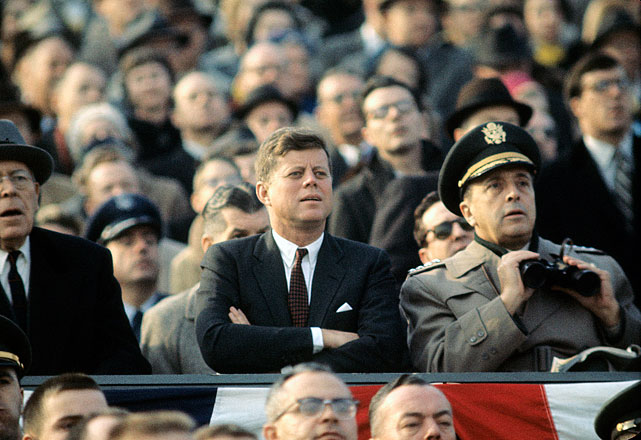

The game is particularly emotional for this reason. Despite intense rivalry, it would be hard to find a duel in all of sports, where the two sides hold the other in higher respect and esteem.

The game is particularly emotional for this reason. Despite intense rivalry, it would be hard to find a duel in all of sports, where the two sides hold the other in higher respect and esteem.

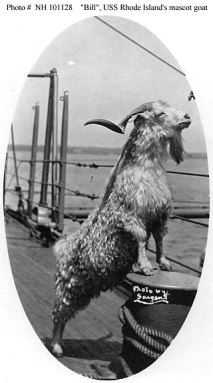

The Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot decided in 1899, that Army needed a mascot in response to the Navy’s goat. Mules have a long history with the United Sates Army, going back to George Washington, the “

The Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot decided in 1899, that Army needed a mascot in response to the Navy’s goat. Mules have a long history with the United Sates Army, going back to George Washington, the “ Always the last regular-season game in Division I-A football, the next four Army-Navy games are scheduled in Philadelphia. The game site will then move to Metlife Stadium in East Rutherford New Jersey, to mark the twenty-year anniversary of the Islamist terror attacks on the World Trade Center. The 2022 game moves back to Philadelphia, marking the 91st time Army and Navy have played there.

Always the last regular-season game in Division I-A football, the next four Army-Navy games are scheduled in Philadelphia. The game site will then move to Metlife Stadium in East Rutherford New Jersey, to mark the twenty-year anniversary of the Islamist terror attacks on the World Trade Center. The 2022 game moves back to Philadelphia, marking the 91st time Army and Navy have played there.

In the Netherlands, ice hockey began sometime in the 16th century. North Americans have played the sport since 1855. For all that time, flying hockey pucks have collided with the faces of goalies. The results could not have been pretty.

In the Netherlands, ice hockey began sometime in the 16th century. North Americans have played the sport since 1855. For all that time, flying hockey pucks have collided with the faces of goalies. The results could not have been pretty.

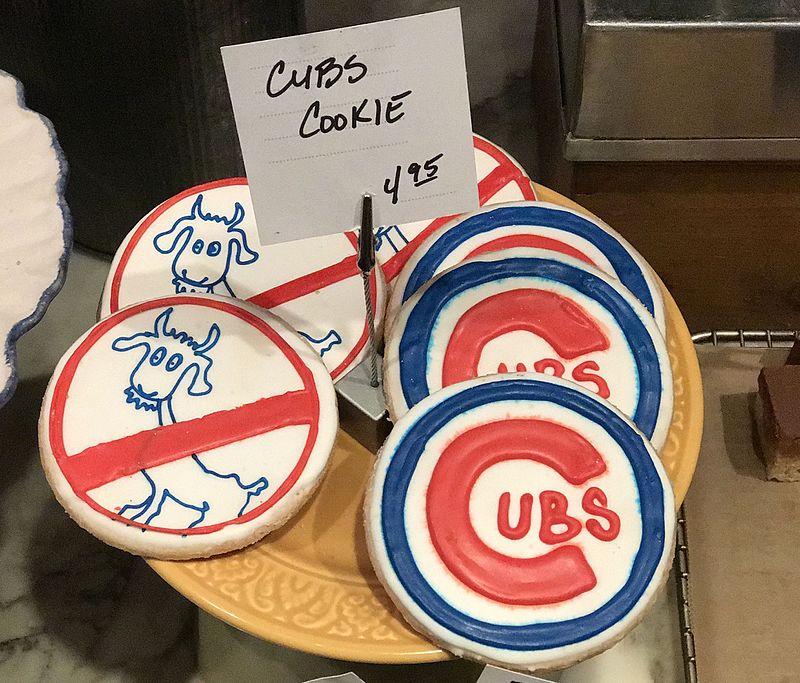

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right?

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right? Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since.

Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since. Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.