Traditionally, the line of succession to the Imperial Russian throne descended through the male line. By 1903 the Tsarina Alexandra had delivered four healthy babies, each of them girls. Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia. In 1904, the Tsarina labored to deliver her fifth.

That August, the country waited and hoped for an heir to the throne. All of Russia prayed for a boy.

The prayers of the nation were answered on August 12 (July 30 Old Style calendar), with the birth of a son. The Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich. The happy news was announced with a 301-gun salute from the cannons of the Peter and Paul fortress, and all of Russia rejoiced.

Those hopes would be dashed in less than a month, when the infant’s navel began to bleed. It continued to bleed for two days, and required all the doctors at the Tsar’s disposal, to stop it.

The child suffered from hemophilia, an hereditary condition passed down from his Grandmother British Queen Victoria. She’d already lost a son and a grandson to the disease, both at the age of three.

The early years of any small boy are punctuated by dents and dings and the Tsarevich was no exception. Bleeding episodes were often severe, despite the never-ending efforts of his parents, to protect him. Doctors’ remedies were frequently in vain, and Alexandra turned to a succession of quacks, mystics and “wise men”, for a cure.

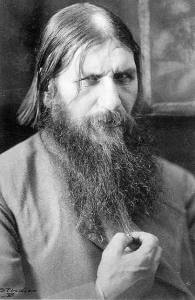

Born on this day in 1869, Grigori Efimovich Rasputin was a strange man, a Siberian peasant wanderer and self-proclaimed “holy man”, a seer of the future claiming the power to heal. Rasputin would leave his home village of Pokrovskoye for months or even years at a time, wandering the countryside and visiting holy sites. It’s rumored that he once went as far Athos in Greece, at that time a center of monastic life in the Orthodox church.

The precise circumstances are unknown, but the monk came into the royal orbit, sometime in 1905. “We had the good fortune”, Tsar Nicholas wrote to his diary , “to meet the man of God Grigori from the province of Tobolsk”.

The precise circumstances are unknown, but the monk came into the royal orbit, sometime in 1905. “We had the good fortune”, Tsar Nicholas wrote to his diary , “to meet the man of God Grigori from the province of Tobolsk”.

Alexei suffered an internal hemorrhage in the spring of 1907, and Grigori was summoned to pray. The Tsarevich recovered the next morning. The royal family came to rely on the faith-healing powers of Rasputin. It seemed that he alone was able to stop the boy’s bleeding episodes.

The Tsarevich developed a serious hematoma in his groin and thigh in 1912, following a particularly jolting carriage ride. Severely in pain and suffering with high fever, the boy appeared to be close to death. Desperate, the Tsarina sent a telegram, asking the monk to pray for her son. Rasputin wrote back from Siberia, “God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.” The bleeding stopped, within the next two days.

The British historian Harold Shukman wrote that Rasputin was “an indispensable member of the royal entourage”.

As the royal family became more attached to the monk Rasputin, scandals followed the peasant holy man like the chains of Jacob Marley. Rumors abounded of sexual peccadillos, involving society ladies and prostitutes alike. Gossip describing trysts between the “Mad Monk” and the Tsarina herself were almost certainly unfounded, but so widespread that pornographic postcards were openly circulated, depicting these liaisons.

What the Tsar and Tsarina saw as a pious and holy man, the Russian nobility saw as a foul smelling, sex-crazed peasant with far too much influence on decisions of State. Alexandra believed the man had the power to make her boy better. Those around her openly spoke of Rasputin ruining the Royal Family, and the Russian nation.

Influential people approached Nicholas and Alexandra with dire warnings, leaving dismayed by their refusal to listen. Rasputin was indispensable according to the Royal Couple. He was the only man who could save the Tsarevich.

By 1916 it was clear to many in the Nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before he destroyed the monarchy.

By 1916 it was clear to many in the Nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before he destroyed the monarchy.

A group of five Nobles led by Prince Felix Yusupov lured Rasputin to the Moika Palace on December 16, 1916, using the possibility of a sexual encounter with Yusopov’s beautiful wife Irina, as bait. Pretending that she was upstairs with unexpected guests, the five “entertained” Rasputin in a basement dining room, feeding him arsenic laced pastries and washing them down with poisoned wine. None of it seemed to have any effect.

Panicked, Yusupov pulled a revolver and shot the monk. Rasputin went down, but soon got up and attacked his tormentors. He tried to run away, only to be shot twice more and have his head beaten bloody with a dumbbell. At last, with hands and feet bound, Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was thrown from a bridge into the icy Malaya Nevka River.

Police found the body two days later, with water in the lungs and hands outstretched. Poisoned, shot in the chest, back and head, with his head stove in, Rasputin was still alive when he hit the water.

In the end, the succession question turned out to be moot. A letter attributed to Rasputin, which he may or may not have written, contained a prophecy. “If I am killed by common assassins and especially by my brothers the Russian peasants, you, Tsar of Russia, have nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia…[I]f it was your relations who have wrought my death…none of your children or relations will remain alive for two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…”

The stresses and economic dislocations of the Great War proved too much to handle. The Imperial Russian state collapsed in 1917. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne within three months of the death of Rasputin. Members of the Ural regional Soviet shot, bludgeoned and bayoneted the Russian Imperial family to death: Tsar Nicholas, his wife Tsarina Alexandra, all five children, the Grand Duchess Olga, the Romanov family physician, their footman, maid, and their dogs.

A coded telegram was sent to Lenin’s secretary, Nikolai Gorbunov. “Inform Sverdlov”, (Communist party administrator Yakov Sverdlov ) “The whole family have shared the same fate as the head. Officially the family will die at the evacuation”.

People began to gather on the 29th. By 5:00am on the 30th, the crowd was estimated at half a million. A rumor began to spread among the crowd that there wasn’t enough beer or pretzels to go around. At that point the police force of 1,800 wasn’t enough to maintain order. The crush of the crowd and the resulting panic resulted in a human stampede. Before it was over 1,389 people were trampled to death, and another 1,300 injured.

People began to gather on the 29th. By 5:00am on the 30th, the crowd was estimated at half a million. A rumor began to spread among the crowd that there wasn’t enough beer or pretzels to go around. At that point the police force of 1,800 wasn’t enough to maintain order. The crush of the crowd and the resulting panic resulted in a human stampede. Before it was over 1,389 people were trampled to death, and another 1,300 injured.

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany, that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring to Germany’s Austro-Hungarian ally. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the Triple Entente side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to breaking. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was on the edge of the precipice.

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany, that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring to Germany’s Austro-Hungarian ally. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the Triple Entente side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to breaking. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was on the edge of the precipice. the more extreme road. While Reds and Whites both wanted to bring socialism to the Russian people, the Mensheviks argued for predominantly legal methods and trade union work, while Bolsheviks favored armed violence.

the more extreme road. While Reds and Whites both wanted to bring socialism to the Russian people, the Mensheviks argued for predominantly legal methods and trade union work, while Bolsheviks favored armed violence.

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”.

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”. In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

birth of a son. The Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich. The public was informed of the happy news with a 301 gun salute from the cannons of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Those hopes would be dashed in less than a month, when the infant’s navel began to bleed. It continued to bleed for two days, and took all the doctors at the Tsar’s disposal to stop it.

birth of a son. The Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich. The public was informed of the happy news with a 301 gun salute from the cannons of the Peter and Paul Fortress. Those hopes would be dashed in less than a month, when the infant’s navel began to bleed. It continued to bleed for two days, and took all the doctors at the Tsar’s disposal to stop it. exception. The bleeding episodes suffered by the Tsarevich were often severe, despite his parents never ending attempts to protect him. Doctors’ efforts were frequently in vain, and Alexandra turned to a succession of quacks, mystics and “wise men” for a cure.

exception. The bleeding episodes suffered by the Tsarevich were often severe, despite his parents never ending attempts to protect him. Doctors’ efforts were frequently in vain, and Alexandra turned to a succession of quacks, mystics and “wise men” for a cure. Influential people approached Nicholas and Alexandra with dire warnings, leaving dismayed by their refusal to listen. According to the Royal Couple, Rasputin was the only man who could save their young son Alexei. By 1916 it was clear to many in the nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before the monarchy was destroyed.

Influential people approached Nicholas and Alexandra with dire warnings, leaving dismayed by their refusal to listen. According to the Royal Couple, Rasputin was the only man who could save their young son Alexei. By 1916 it was clear to many in the nobility. The only course was to kill Rasputin, before the monarchy was destroyed. nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia…[I]f it was your relations who have wrought my death…none of your children or relations will remain alive for two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…”

nothing to fear for your children, they will reign for hundreds of years in Russia…[I]f it was your relations who have wrought my death…none of your children or relations will remain alive for two years. They will be killed by the Russian people…”

You must be logged in to post a comment.