In 688, Pepin of Herstal was Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia; the Frankish Kingdom occupying what is now northern France, Belgium and parts of Germany. Pepin was the power behind the throne, King in all but name, controlling the royal treasury, dispensing patronage, and granting land and privileges in the name of a figurehead King.

Pepin kept a mistress, the noblewoman Alpaida, with whom he had two sons, Childebrand and Charles. The former went on to become a minor Duke. The latter, the founding father of the European Middle Ages.

Pepin’s only legitimate male heir predeceased him in 714, touching off a succession crisis with the naming of his 8-year-old grandson Theudoald his True Successor. The child’s grandmother, Pepin’s wife Plectrude, threw Charles in prison, but he escaped and rose to power in the Civil War which followed.

Charles showed himself to be a brilliant Military tactician, crushing a far superior army at the Battle of Ambleve. Returning victorious in 718, he did something unusual for the time. He showed kindness to the boy Theudoald and his grandmother.

Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, subjugating Bavarians, Allemanii, and pagan Saxons, and combining the formerly separate Kingdoms of Nuestria in the northwest of modern-day France with that of Austrasia in the east.

At this time a storm was building to the west, in the form of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania. The Caliphate gained control of most of the Iberian peninsula beginning in 711, before invading eastward into Gaul.

The Umayyad conquest suffered a setback in 721, when forces under Odo the Great, Duke of Acquitaine, broke the siege of Toulouse. The Emir then built a strong force out of Yemen, Syria and Morocco and, in 732, invaded again. This time Odo was destroyed in a crushing defeat at the Battle of the River Garonne. So great was the slaughter of Christians that the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, a contemporary Latin source, said “God alone knows the number of the slain”.

Odo fled to Charles asking for help, and the scene was set for one of the most decisive battles in world history.

The Umayyad Caliphate had recently defeated two of the most powerful militaries of its time. The Sassanid empire in modern day Iran had been destroyed altogether, as had the greater part of the Byzantine Empire, including Armenia, North Africa and Syria.

Other than the Frankish Kingdom, there was no force sufficient to stop the advance of the Umayyad Caliphate. Many historians believe that, if not for the Battle of Tours, the Islamic Conquest would have overrun Gaul and the rest of Western Europe, resulting in a single Caliphate stretching from the Sea of Japan to the English Channel.

Estimates vary regarding the size of the two armies. The forces of Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi are estimated to have been 80,000 horse and foot soldiers on the day of battle. There were about 30,000 on the Frankish side.

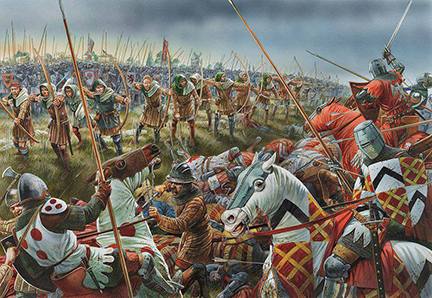

Outnumbered more than two to one and having no cavalry of his own, Charles took his advantages where he could find them. Charles’ tough, battle hardened infantry had been with him for years, and he was able to choose the ground on which to give battle. Each man in the Frankish army wore up to 75lbs of armor, and every one of them believed in Charles’ leadership. Taking to high ground between the villages of Tours and Poitiers, the Frankish host drew itself into a great, bristling square formation to withstand the shock of the cavalry charge. And there, it waited.

Having nothing but contempt for what they saw as backward, irreligious heathens, the Saracen host was stunned to discover the army awaiting them. For seven days, the two armies stood facing one another, with little but skirmishes between them. Finally, the Emir could wait no longer. It was late in the year and his men were not equipped for a European winter. On the seventh day, estimated to be the 10th of October in the year 732, al Ghafiqi ordered his cavalry to charge.

History offers few instances of medieval armies withstanding the charge of cavalry, but Charles had anticipated this moment. He had trained his men, and they were prepared.

The Mozarabic Chronicle describes the scene in greater detail than any source, Latin or Arab: “[I]n the shock of the battle the men of the North seemed like a sea that cannot be moved. Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice; and with great blows of their swords they hewed down the Arabs. Drawn up in a band around their chief, the people of the Austrasians carried all before them. Their tireless hands drove their swords down to the breasts [of the foe].”

A few Umayyad troops succeeded in breaking into the square and went directly for Charles, but his liege men surrounded him and would not be broken. The battle was still in flux when rumors went through the Muslim host that Charles’ men had broken into the Umayyad base camp. Afraid of having the loot they had plundered at Bordeaux taken from them, many of them broke off the battle to return to camp. Abdul Rahman was trying to stop the retreat, when he was surrounded and killed.

Wary of a “feigned flight” attack, the Franks resumed their phalanx. There they stood all night and into the next day, until it was discovered that the Islamic host had fled in the night.

Following the Battle of Tours, (Poitiers), the bastard son of Pepin and father of Charlemagne would, henceforward and forever, be known as Charles “the Hammer” Martel.

The threat was far from over in 732. New Umayyad assaults would threaten northern Europe in 736 and 739, until internal conflicts divided the Caliphate against itself, the feudal Arab Empire of the Umayyads falling to the multi-ethnic Empire of the Abbassid Caliphate of Baghdad in 750, the third Caliphate in the early history of Islam.

The reconquest of “al-Andalus” would be another 760 years, in the making. The “Golden age” of Islam ended with the sack of Baghdad in 1268 by the Mongols of Hulagu Khan, making way for the rise of the Ottoman Empire of the Seljuq Turk. Forces of this “Ottoman Caliphate” conquered the last vestige of the eastern Roman empire in 1453.

Ottoman forces attempted the conquest of Europe from the east, taking Vienna under siege in 1529 and again in 1683, as well as Malta, in 1565. Famagusta, the last Christian possession in the eastern Mediterranean island nation of Cyprus, held out for eleven months, in 1570-1. 8,500 Venetian defenders, against the 200,000-strong Ottoman forces under General Lala Mustafa Pasha.

Commander Marcantonio Bragadin would be flayed alive and stuffed with straw as a grisly trophy of war, together with the heads of the Venetian commanders, Astorre Baglioni, Alvise Martinengo and Gianantonio Querini. Yet this desperate and doomed defense of the last stronghold on Cyprus bought Pope Pius V time to cobble together an anti-Ottoman “Holy League” coalition among the Catholic states of Europe. Ottoman naval power was destroyed for all time in 1571 near a place called Lepanto. The largest naval battle in Western history, since classical antiquity.

Conflict between Cross and Crescent would continue far into the future of Charles Martel, but, Christian Europe would never again, be so grievously challenged.

Tostig sailed for England with King Harald and a mighty army of 10,000 Viking warriors, meeting the northern Earls Edwin and Morcar in battle at Fulford Gate, on September 20.

Tostig sailed for England with King Harald and a mighty army of 10,000 Viking warriors, meeting the northern Earls Edwin and Morcar in battle at Fulford Gate, on September 20.

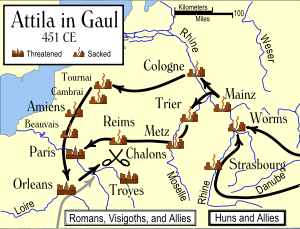

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

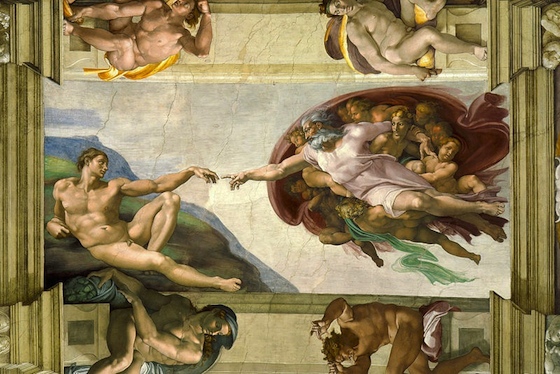

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

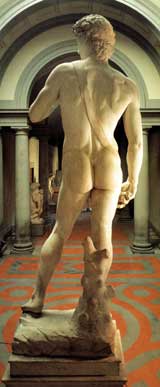

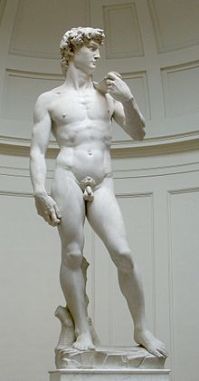

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther.

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther. Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20. The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem?

The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem? the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

It’s a fairy tale, to some degree, but at least parts of the story appear to be historically accurate. The part about the rats was added 200 years later and the magic flute is a little hard to believe, but the town of Hamelin part is real enough.

It’s a fairy tale, to some degree, but at least parts of the story appear to be historically accurate. The part about the rats was added 200 years later and the magic flute is a little hard to believe, but the town of Hamelin part is real enough.

Others believe such outbreaks to be evidence of Sydenham’s chorea, a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet and closely associated with a medical history of Rheumatic fever. Particularly in children.

Others believe such outbreaks to be evidence of Sydenham’s chorea, a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet and closely associated with a medical history of Rheumatic fever. Particularly in children.

You must be logged in to post a comment.