It was September 8, 2004, less than two months before the 2004 Presidential election. CBS News aired a 60 Minutes™ broadcast hosted by News Anchor Dan Rather, centered on four documents critical of President George W. Bush’s National Guard service in 1972-‘73. The documents were supposed to have been written by Bush’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Jerry B. Killian, who’d passed away in 1984.

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. He later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered Burkett to be an “anti-Bush zealot”.

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. He later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered Burkett to be an “anti-Bush zealot”.

Within hours of the broadcast, the documents were criticized as forgeries. Internet forums and blogs challenged the terminology and typography of the memos. Within days it came out that the font used in the memos didn’t exist at the time the documents were supposed to have been written.

That didn’t stop the Boston Globe from running a story entitled “Authenticity Backed on Bush Documents”, a story they later had to retract.

Criticism of the 60 Minutes’ piece intensified, as CBS News and Dan Rather dug in and defended their story. Within the week, Rather was talking to a Daily Kos contributor and former typewriter repairman who claimed that the documents could have been written in the 70s. Meanwhile, the four “experts” used in the original story were publicly repudiating the 60 Minutes piece.

Other aspects of the documents were difficult to authenticate without access to the originals. CBS had nothing but faxes and photocopies, and Burkett claimed to have burned the originals after faxing them to the network.

The New York Times interviewed Marian Carr Knox who’d been secretary to the squadron in 1972, running a story dated September 14 under the bylines of Maureen Balleza and Kate Zernike. The headline read “Memos on Bush Are Fake but Accurate, Typist Says“.

The New York Times interviewed Marian Carr Knox who’d been secretary to the squadron in 1972, running a story dated September 14 under the bylines of Maureen Balleza and Kate Zernike. The headline read “Memos on Bush Are Fake but Accurate, Typist Says“.

The story went on to describe the 86 year-old Carr’s recollections that she never typed the memos, but they accurately reflected the feelings of Lt. Col. Killian. “I think he was writing the memos”, she said, “so there would be some record that he was aware of what was going on and what he (Bush) had done.”

Yet Killian’s wife and son had cleared out his office after his death, and they didn’t find anything even hinting at the existence of such documents. Others who claimed to know Carr well described her as a “sweet old lady”, but said they had “no idea” where her statements had come from.

CBS News would ultimately retract the story, as it came out that Producer Mary Mapes collaborated on it with the Kerry campaign. Several network news people lost their jobs, including Rather and Mapes.

Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing to it.

Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing to it.

“Conservative” news sources like PJ Media rose in the aftermath, a tongue-in-cheek reference to the fact that a bunch of bloggers “in their jammies”, uncovered in hours what the vaunted news gathering apparatus of CBS News failed to figure out in weeks.

Such news media bias is nothing new. In 1932-33, New York Times reporter Walter Duranty reported on Josef Stalin’s deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainians, known as “Holodomor”. “Extermination by hunger”. With 25,000 starving to death every day, Duranty won a Pulitzer with such gems as: “There is no famine or actual starvation nor is there likely to be.” – (Nov. 15, 1931), and, “Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.” – (Aug. 23, 1933).

The 1993 NBC Dateline “Exploding Truck” edition didn’t get the desired effect when they crash tested that pickup truck, so they rigged another one with a pyrotechnic device. Sure enough, that one exploded on cue. The “Exposé” was fiction masquerading as “News”, but hey. The explosion made good television.

In a transparent attack on an administration with which it had political disagreements, the New York Times ran the Abu Ghraib story on the front page, above the fold, for 32 days straight. Just in case anyone missed the first 31.

And who can forget that edited audio from George Zimmermann’s 911 call. Thank you, NBC.

If the point requires further proof, watch ABC News Charlie Gibson’s 2008 interview with Sarah Palin, then read the transcript. Whether you like or don’t like Ms. Palin is irrelevant to the point. The transcript and the interview as broadcast, are two different things.

The political process is afflicted when news agencies act as advocates in the stories they cover. Our system of self-government cannot long survive without an informed electorate. That may be the worst part of this whole sorry story.

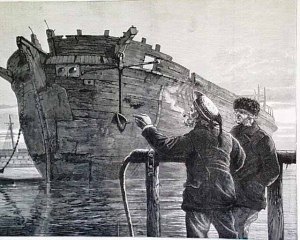

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased by the English government in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the Franklin expedition, which had disappeared into the ice pack in 1845.

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased by the English government in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the Franklin expedition, which had disappeared into the ice pack in 1845.

Hawk” Raymond had a favor to ask of then-Governor Coke Robert Stevenson. They wanted the Governor to appoint a Raymond relative, E. James Kazen, as Laredo district attorney.

Hawk” Raymond had a favor to ask of then-Governor Coke Robert Stevenson. They wanted the Governor to appoint a Raymond relative, E. James Kazen, as Laredo district attorney. Texas had only a weak Republican party in 1948. The winner of the Democrat’s three-way primary was sure to be the next Senator.

Texas had only a weak Republican party in 1948. The winner of the Democrat’s three-way primary was sure to be the next Senator.

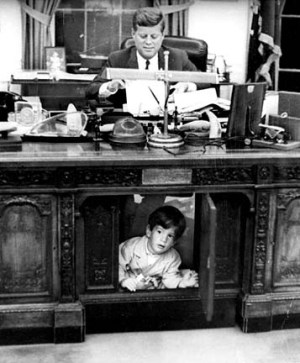

assassination of John F Kennedy, a man whom many believe stole his own election from Richard Nixon in 1960, with the help of Chicago’s Daley machine and a little creative vote counting in Cook County.

assassination of John F Kennedy, a man whom many believe stole his own election from Richard Nixon in 1960, with the help of Chicago’s Daley machine and a little creative vote counting in Cook County.

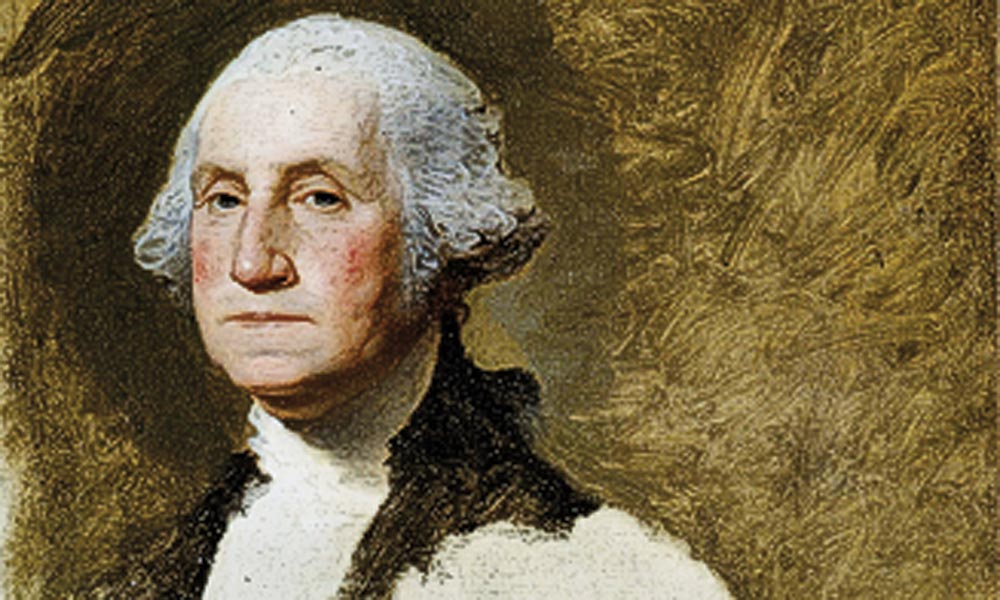

More shooting incidents occurred in the days that followed. Objections to the whiskey tax gave way to a long list of economic grievances, as over 7,000 gathered in Braddock’s Field on August 1. They talked of secession and carried their own flag, each of its six stripes representing one of 6 Pennsylvania or eastern Ohio counties.

More shooting incidents occurred in the days that followed. Objections to the whiskey tax gave way to a long list of economic grievances, as over 7,000 gathered in Braddock’s Field on August 1. They talked of secession and carried their own flag, each of its six stripes representing one of 6 Pennsylvania or eastern Ohio counties. The whiskey rebellion collapsed in the face of what was then an overwhelming army, with 10 of their leaders brought to Philadelphia to stand trial. Two were sentenced to hang for their role in the rebellion, but President Washington pardoned them both. The whiskey rebellion was over.

The whiskey rebellion collapsed in the face of what was then an overwhelming army, with 10 of their leaders brought to Philadelphia to stand trial. Two were sentenced to hang for their role in the rebellion, but President Washington pardoned them both. The whiskey rebellion was over.

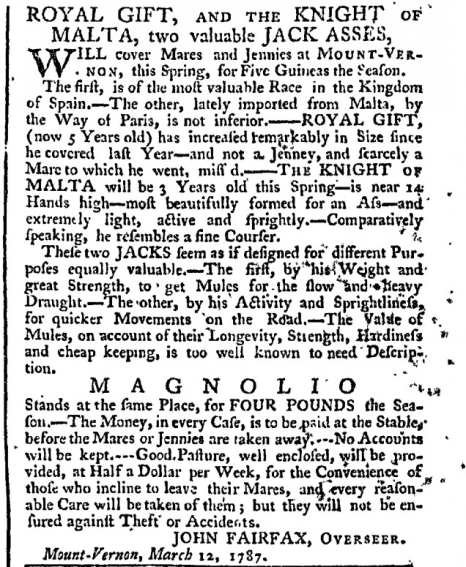

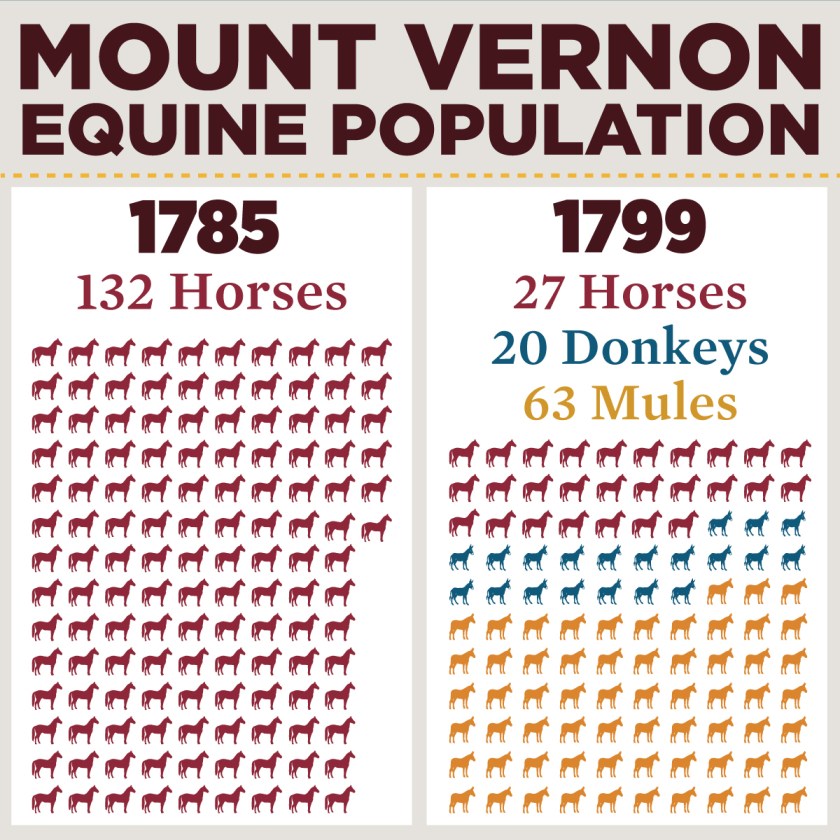

Mules are hybrid animals, the offspring of a male Equus Africanus Asinus, and a female Equus Caballus. A jackass and a mare. From the sire, the mule inherits intelligence, toughness and endurance, while the dam passes down her speed, conformation and agility.

Mules are hybrid animals, the offspring of a male Equus Africanus Asinus, and a female Equus Caballus. A jackass and a mare. From the sire, the mule inherits intelligence, toughness and endurance, while the dam passes down her speed, conformation and agility.

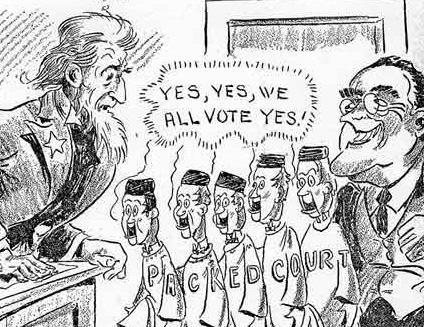

Realist” or “Liberal” legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution was a “living document”, allowing for judicial flexibility and legislative experimentation. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a leading proponent of the Realist philosophy, said of Missouri v. Holland that the “case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago”.

Realist” or “Liberal” legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution was a “living document”, allowing for judicial flexibility and legislative experimentation. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a leading proponent of the Realist philosophy, said of Missouri v. Holland that the “case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago”. To Roosevelt, that was the answer. The age 70 provision allowed him 6 more handpicked justices, effectively ending Supreme Court opposition to his policies.

To Roosevelt, that was the answer. The age 70 provision allowed him 6 more handpicked justices, effectively ending Supreme Court opposition to his policies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.