Over the night and the following day of April 18-19, 1775, individual British soldiers marched 36 miles or more, on the round-trip expedition from Boston. Following the early morning battles at Lexington and Concord, armed colonial militia from as far away as Worcester swarmed over the column, forcing the regulars into a fighting retreat.

In those days, Boston was a virtual island, connected to the mainland by a narrow “neck” of land. More than 20,000 armed men converged from all over New England in the weeks that followed, gathering in buildings and encampments from Cambridge to Roxbury.

A man who should have gone into history among the top tier of American Founding Fathers, the future turncoat Benedict Arnold, arrived with Connecticut militia to support the siege. Arnold informed the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that Fort Ticonderoga, located along the southern end of Lake Champlain in northern New York, was bristling with cannon and other military stores. Furthermore, the place was lightly defended.

A man who should have gone into history among the top tier of American Founding Fathers, the future turncoat Benedict Arnold, arrived with Connecticut militia to support the siege. Arnold informed the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that Fort Ticonderoga, located along the southern end of Lake Champlain in northern New York, was bristling with cannon and other military stores. Furthermore, the place was lightly defended.

The committee commissioned Arnold a colonel on May 3, authorizing him to raise troops and lead a mission to capture the fort. Seven days later, Colonel Arnold and militia forces from Connecticut and western Massachusetts in conjunction with Ethan Allen and his “Green Mountain Boys” captured the fort, and all its armaments.

The Continental Congress created the Army that June, appointing General George Washington to lead it. When General Washington took command of that army in July, it was a force with an average of nine rounds-worth of shot and powder, per man. British forces occupying Boston, were effectively penned up by forces too weak to do anything about it.

The stalemate dragged on for months, when a 25-year-old bookseller came to General Washington with a plan. His name was Henry Knox. His plan was a 300-mile, round trip slog into a New England winter, to retrieve the guns of Ticonderoga: brass and iron cannon, howitzers, and mortars. 59 pieces in all. Washington’s advisors derided the idea as hopeless, but the General approved.

![]()

Knox set out with a column of men in late November, 1775. For nearly two months, he and his team wrestled 60 tons of cannons and other armaments by boat, animal & man-hauled sledges along roads little better than foot trails. Across two barely frozen rivers, and through the forests and swamps of the Berkshires to Cambridge, historian Victor Brooks called it “one of the most stupendous feats of logistics” of the Revolution. It must have been a sight on January 24, 1776, when Knox returned at the head of that “Noble Train of Artillery”.

For British military leadership in Boston, headed by General William Howe, the only option for resupply was by water, via Boston Harbor. Both sides of the siege understood the strategic importance of the twin prominences overlooking the harbor, the hills of Charlestown to the north, and Dorchester heights to the south. It’s why British forces had nearly spent themselves on Farmer Breed’s hillside that June, an engagement that went into history as the Battle of Bunker Hill.

With Howe’s forces in possession of the Charlestown peninsula, Washington had long considered occupying Dorchester Heights, but considered his forces too weak. That changed with the guns of Ticonderoga.

In the first days of March, Washington placed several heavy cannon at Lechmere’s Point and Cobble Hill in Cambridge, and on Lamb’s Dam in Roxbury. The batteries opened fire on the night of March 2, and again on the following night and the night after that. With British attention thus diverted, American General John Thomas and a force of some 2,000 made plans to take the heights.

As the ground was frozen and digging impossible, fortifications and cannon placements were fashioned from heavy 10′ timbers. With the path to the top lined with hay bales to muffle their sounds, these fortifications were manhandled to the top of Dorchester heights over the night of March 4-5, along with the bulk of Knox’ cannons.

General Howe was stunned on awakening, on the morning of March 5. The British garrison in Boston and the fleet in harbor, were now under the muzzles of Patriot guns. “The rebels have done more in one night”, he said, “than my whole army would have done in a month.”

Plans were laid for an immediate British assault on the hill, as reinforcements poured into the position. By day’s end, Howe faced the prospect of another bunker Hill, this time against a force of 6,000 in possession of heavy artillery.

A heavy snowstorm descended late in the day, interrupting Howe’s plan for the assault. A few days later, he had thought better of it. A tacit cease-fire settled in over the next two weeks, with Washington’s side declining to open fire, and Howe’s side refraining from destroying the town, in the course of withdrawing from Boston.

British forces departed Boston by sea on March 17 with about 1,000 civilian loyalists, resulting in a peculiar Massachusetts institution which exists to this day. “Evacuation Day”:

It’s doubtful whether Washington possessed either powder or shot for a sustained campaign, but British forces occupying Boston didn’t know that. The mere presence of those guns moved General Howe to weigh anchor and sail for Nova Scotia. The episode may be the greatest head fake, in military history.

“Filled with mingled cream and amber

“Filled with mingled cream and amber

D’Estaing sent an ultimatum to British Commander Augustine Prevost on September 16, 1779. He was to surrender the city “To the arms of his Majesty the King of France”, or he would be personally answerable for what was about to happen. It could not have pleased General Benjamin Lincoln or his Patriot allies when d’Estaing added “I have not been able to refuse the army of the United States uniting itself with that of the King. The junction will probably be effected this day. If I have not an answer therefore immediately, you must confer with General Lincoln and me”.

D’Estaing sent an ultimatum to British Commander Augustine Prevost on September 16, 1779. He was to surrender the city “To the arms of his Majesty the King of France”, or he would be personally answerable for what was about to happen. It could not have pleased General Benjamin Lincoln or his Patriot allies when d’Estaing added “I have not been able to refuse the army of the United States uniting itself with that of the King. The junction will probably be effected this day. If I have not an answer therefore immediately, you must confer with General Lincoln and me”.

The American Revolution was on its last legs in December 1776. The year had started out well for the Patriot cause but turned into a string of disasters, beginning in August. Food, ammunition and equipment were in short supply by December. Men were deserting as the string of defeats brought morale to a new low. Most of those who remained, ended enlistments at the end of the year.

The American Revolution was on its last legs in December 1776. The year had started out well for the Patriot cause but turned into a string of disasters, beginning in August. Food, ammunition and equipment were in short supply by December. Men were deserting as the string of defeats brought morale to a new low. Most of those who remained, ended enlistments at the end of the year.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

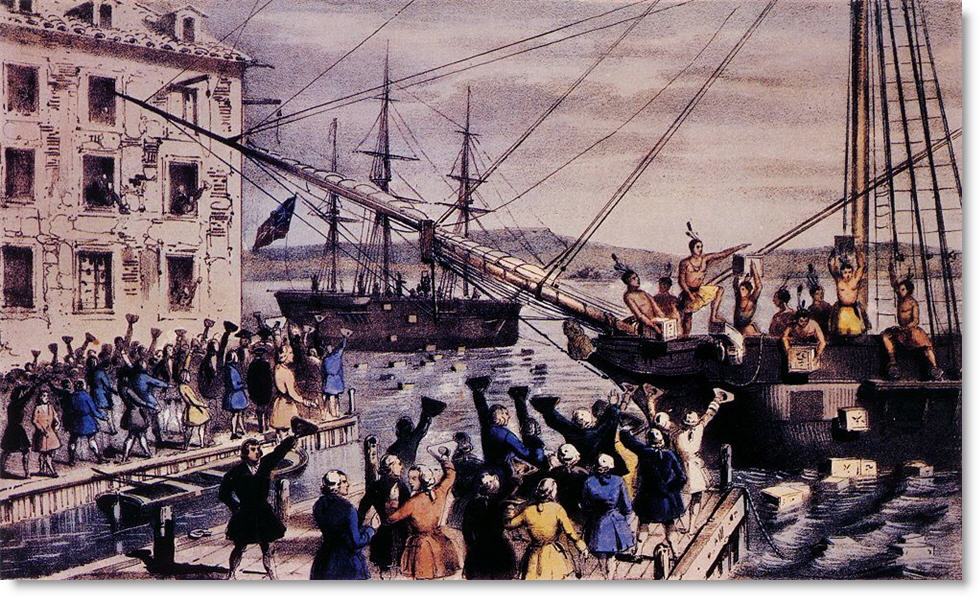

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

Juan Garrido moved from the west coast of Africa to Lisbon, Portugal, possibly as a slave, or perhaps the son of an African King, sent for a Christian education. Be that as it may, Garrido came to the new world a free man in 1513, with Juan Ponce de León. A black Conquistador who spent thirty years with the conquest, “pacifying” (fighting) indigenous peoples and searching for gold, and the mythical fountain of youth.

Juan Garrido moved from the west coast of Africa to Lisbon, Portugal, possibly as a slave, or perhaps the son of an African King, sent for a Christian education. Be that as it may, Garrido came to the new world a free man in 1513, with Juan Ponce de León. A black Conquistador who spent thirty years with the conquest, “pacifying” (fighting) indigenous peoples and searching for gold, and the mythical fountain of youth. The Spanish government in Florida began to offer asylum to slaves from British colonies as early as 1687, when eight men, two women and a three year old nursing child arrived there, seeking refuge. It probably wasn’t as altruistic as it sounds, given the history. The primary interest seems to have been disrupting the English agricultural economy, to the north.

The Spanish government in Florida began to offer asylum to slaves from British colonies as early as 1687, when eight men, two women and a three year old nursing child arrived there, seeking refuge. It probably wasn’t as altruistic as it sounds, given the history. The primary interest seems to have been disrupting the English agricultural economy, to the north.

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

You must be logged in to post a comment.