In 1861, leader of the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe band Ahgamahwegezhig, or “Chief Big Sky”, captured an eaglet, and sold it for a bushel of corn to the McCann family of Chippewa County, Wisconsin. Captain John Perkins, Commanding Officer of the Eau Claire “Badgers”, bought the young bald eagle from Daniel McCann.

The asking price was $2.50. Militia members were asked to pitch in twenty-five cents, as was one civilian: tavern-keeper S.M. Jeffers. Jeffers’ refusal earned him “three lusty groans”, causing him to laugh and tell them to keep their quarters. Jeffers threw in a single quarter-eagle, a gold coin valued at 250¢, and that was that. From that moment onward, the militia unit called itself the Eau Claire “Eagles”.

Perkins’ Eagles entered Federal Service as Company C of the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. It wasn’t long before the entire Regiment adopted the bald eagle, calling themselves the “Eagle Regiment”, in honor of their new mascot. Much deliberation followed as to what to name him, before it was decided. He would be called “Old Abe”.

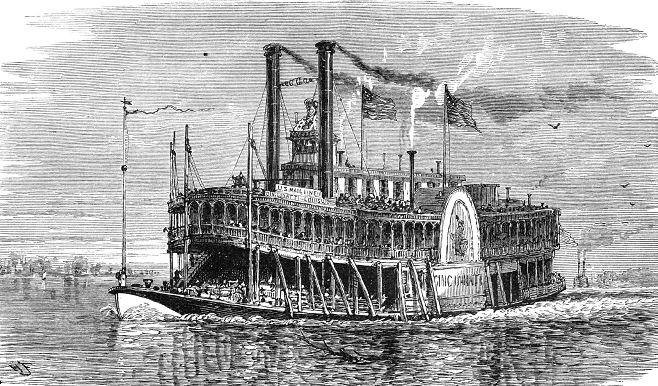

Old Abe accompanied the regiment as it headed south, travelling all over the western theater and witness to 37 battles. David McLain wrote “I have frequently seen Generals Grant, Sherman, McPherson, Rosecrans, Blair, Logan, and others, when they were passing our regiment, raise their hats as they passed Old Abe, which always brought a cheer from the regiment and then the eagle would spread his wings”.

Abe became an inspirational symbol to the troops, like the battle flag carried with each regiment. Colonel Rufus Dawes of the Iron Brigade recalled, “Our eagle usually accompanied us on the bloody field, and I heard [Confederate] prisoners say they would have given more to capture the eagle of the Eighth Wisconsin, than to take a whole brigade of men.”

Abe became an inspirational symbol to the troops, like the battle flag carried with each regiment. Colonel Rufus Dawes of the Iron Brigade recalled, “Our eagle usually accompanied us on the bloody field, and I heard [Confederate] prisoners say they would have given more to capture the eagle of the Eighth Wisconsin, than to take a whole brigade of men.”

Confederate General Sterling Price spotted Old Abe on his perch during the battle of Corinth, Mississippi. “That bird must be captured or killed at all hazards”, Price remarked. “I would rather get that eagle than capture a whole brigade or a dozen battle flags”.

Old Abe was presented to the state of Wisconsin at the end of the war. He lived 15 years in the “Eagle Department”, a two-room apartment in the basement of the Capitol, complete with custom bathtub, and a caretaker. Photographs of Old Abe were sold to help veteran’s organizations. He was a national celebrity, traveling across the country and appearing at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the 1880 Grand Army of the Republic National Convention, and dozens of fundraising events.

A small fire broke out in a Capitol basement workshop, fed by cleaning solvents and shop rags. The fire was quickly extinguished thanks to the bald eagle’s cries of alarm, but not before Old Abe inhaled a whole lot of that thick, black smoke. Abe’s health began to decline, almost immediately. Veterinarians and doctors were called, but to no avail. Bald eagles have been known to live as long as 50 years in captivity. Old Abe died in the arms of caretaker George Gilles on March 26, 1881. He was 20.

His remains were stuffed and mounted. For the next 20 years his body remained on display in the Capitol building rotunda. On the night of February 26, 1904, a gas jet ignited a newly varnished ceiling, burning the Capitol building to the ground.

Since 1915, Old Abe’s replica has watched over the Wisconsin State Assembly Chamber of the new capitol building.

In 1921, the 101st infantry division was reconstituted in the Organized Reserves with headquarters in Milwaukee. It was here that the 101st first became associated with the “Screaming Eagle”. The Screaming Eagles of the 101st Airborne participated in the D-Day invasion, the Battle of the Bulge, Operation Market Garden, and Bastogne, becoming the basis of the HBO series “A Band of Brothers”.

After WWII, elements of the 101st Airborne were mobilized to Little Rock by President Eisenhower to protect the civil rights of the “Little Rock Nine”, a group of black students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in September 1957, as the result of the US Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in the historic Brown v. Board of Education case.

After WWII, elements of the 101st Airborne were mobilized to Little Rock by President Eisenhower to protect the civil rights of the “Little Rock Nine”, a group of black students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in September 1957, as the result of the US Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in the historic Brown v. Board of Education case.

For 104 years, Old Abe appeared in the trademark of the J.I. Case farm equipment company of Racine, Wisconsin.

Winston Churchill once said “A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on.” We all know how stories change with the retelling. Some stories take on a life of their own. Ambrose Armitage, serving with Company D of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry, wrote in his diary on September 14, 1861, that Company C had a “four month old female eagle with them”. Two years later, Armitage wrote, “The passing troops have been running in as they always do to see our eagle. She is a great wonder”.

Ten years after his death, a national controversy sprang up and lasted for decades, as to whether Old Abe was, in fact, a “she”. Suffragettes claimed that “he” had laid eggs in the Wisconsin capitol. Newspapers weighed in, including the Washington Post, Detroit Free Press, St. Louis Post Dispatch, Oakland Tribune, and others.

Bald eagles are not easily sex-differentiated, there are few clues available to the non-expert, outside of the contrasts of a mated pair. It’s unlikely that even those closest to Old Abe, had a clue as to the eagle’s sex.

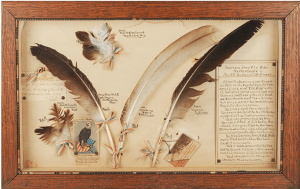

University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center Sequencing Facility researchers had access to four feathers, collected during the early days at the Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Hall. In March of 2016, samples were taken from the hollow quill portion (calamus) of each feather, and examined for the the presence of two male sex chromosomes (ZZ) or both a male and female chromosome (ZW). After three months, the results were conclusive. All four samples showed the Z chromosome, none having a matching W. After 155 years, Old Abe could keep his name.

The 1862 Civil War Battle of Fort Donelson secured the name, when then-Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant received a request for terms from the fort’s commanding officer, Confederate Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner. Grant’s reply was that “no terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately, upon your works.” The legend of “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, was born.

The 1862 Civil War Battle of Fort Donelson secured the name, when then-Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant received a request for terms from the fort’s commanding officer, Confederate Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner. Grant’s reply was that “no terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately, upon your works.” The legend of “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, was born. later, going on to serve two terms after becoming, at that time, the youngest man ever so elected.

later, going on to serve two terms after becoming, at that time, the youngest man ever so elected. In June 1885, as the cancer spread through his body, the family moved to Mount MacGregor, New York, to make him more comfortable. Propped up on chairs and too weak to walk, Grant worked to finish the book as friends, admirers and even former Confederate adversaries, made their way to Mount MacGregor to pay their respects.

In June 1885, as the cancer spread through his body, the family moved to Mount MacGregor, New York, to make him more comfortable. Propped up on chairs and too weak to walk, Grant worked to finish the book as friends, admirers and even former Confederate adversaries, made their way to Mount MacGregor to pay their respects.

Mosby participated in the 1st Battle of Manassas (1st Bull Run) as a member of the Virginia Volunteers Mounted Rifles, later joining James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart as a Cavalry Scout. A natural horseman and gifted tactician, information gathered by Mosby aided Stuart in his humiliating ride around McLellan’s Army of the Potomac in June, 1862.

Mosby participated in the 1st Battle of Manassas (1st Bull Run) as a member of the Virginia Volunteers Mounted Rifles, later joining James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart as a Cavalry Scout. A natural horseman and gifted tactician, information gathered by Mosby aided Stuart in his humiliating ride around McLellan’s Army of the Potomac in June, 1862. Courthouse, Virginia. Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton was sleeping in his headquarters there, some sources say he was “sleeping it off”. The Gray Ghost entered the Union General’s headquarters in the small hours of March 9, his rangers quickly overpowering a handful of sleepy guards.

Courthouse, Virginia. Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton was sleeping in his headquarters there, some sources say he was “sleeping it off”. The Gray Ghost entered the Union General’s headquarters in the small hours of March 9, his rangers quickly overpowering a handful of sleepy guards.

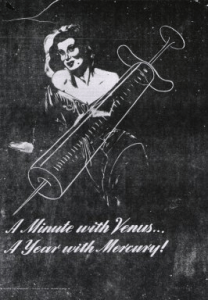

Spalding, Provost Marshal of Nashville, to get rid of them. Though a Catholic, “Old Rosy’s” objection wasn’t based on moral grounds. He was afraid of disease. 8.2% of all Union soldiers were afflicted with syphilis or gonorrhea in 1862, over half the battle casualty rate of 17.5% Venereal disease was a major problem, and the only available treatments at the time involved mercury. Without getting into details, that could take a man out for weeks. Advanced cases were nothing short of grotesque.

Spalding, Provost Marshal of Nashville, to get rid of them. Though a Catholic, “Old Rosy’s” objection wasn’t based on moral grounds. He was afraid of disease. 8.2% of all Union soldiers were afflicted with syphilis or gonorrhea in 1862, over half the battle casualty rate of 17.5% Venereal disease was a major problem, and the only available treatments at the time involved mercury. Without getting into details, that could take a man out for weeks. Advanced cases were nothing short of grotesque.

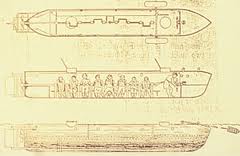

build a secret Super Weapon for the Confederacy. A submarine. They completed construction on their first effort, the “Pioneer”, that same year in New Orleans. The trio went on to build two more submarines in Mobile, Alabama, the “American Diver”, and their last and most successful creation, the “Fishboat”, later renamed HL Hunley.

build a secret Super Weapon for the Confederacy. A submarine. They completed construction on their first effort, the “Pioneer”, that same year in New Orleans. The trio went on to build two more submarines in Mobile, Alabama, the “American Diver”, and their last and most successful creation, the “Fishboat”, later renamed HL Hunley. The original plan was to tow a floating mine called a “torpedo”, with a contact fuse. They would dive beneath their victim and surface on the other side, pulling the torpedo into the side of the target.

The original plan was to tow a floating mine called a “torpedo”, with a contact fuse. They would dive beneath their victim and surface on the other side, pulling the torpedo into the side of the target.

Charleston Navy Yard, and submerged in 55,000 gallons of chilled, fresh water, where scientists and historians worked on unlocking its secrets.

Charleston Navy Yard, and submerged in 55,000 gallons of chilled, fresh water, where scientists and historians worked on unlocking its secrets.

Ambrose Bierce was born in Horse Cave Creek, Ohio, to Marcus Aurelius and Laura Sherwood Bierce, the 10th of 13 children, all with names beginning with the letter “A”.

Ambrose Bierce was born in Horse Cave Creek, Ohio, to Marcus Aurelius and Laura Sherwood Bierce, the 10th of 13 children, all with names beginning with the letter “A”. number on speed dial. In Bierce’s day, he’d better carry a gun. Ambrose Bierce didn’t shy away from politics, he jumped right in, frequently using a mock dictionary definition to lampoon his targets. One example and my personal favorite, is “Politics: A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage”.

number on speed dial. In Bierce’s day, he’d better carry a gun. Ambrose Bierce didn’t shy away from politics, he jumped right in, frequently using a mock dictionary definition to lampoon his targets. One example and my personal favorite, is “Politics: A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage”.

off limits. Politics was a favorite target of his columns, such as: “CONSERVATIVE, n: A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal who wishes to replace them with others”, or “POLITICIAN, n. An eel in the fundamental mud upon which the superstructure of organized society is reared. When he wriggles he mistakes the agitation of his tail for the trembling of the edifice. As compared with the statesman, he suffers the disadvantage of being alive”.

off limits. Politics was a favorite target of his columns, such as: “CONSERVATIVE, n: A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal who wishes to replace them with others”, or “POLITICIAN, n. An eel in the fundamental mud upon which the superstructure of organized society is reared. When he wriggles he mistakes the agitation of his tail for the trembling of the edifice. As compared with the statesman, he suffers the disadvantage of being alive”. Gwinnett Bierce was executed by firing squad in the town cemetery. It’s as good an ending to this story as any, as one hundred and three years ago today is as good a day as any on which to end it. The fact is that in that 103 years, there’s never been a trace of what became of him, and probably never will be.

Gwinnett Bierce was executed by firing squad in the town cemetery. It’s as good an ending to this story as any, as one hundred and three years ago today is as good a day as any on which to end it. The fact is that in that 103 years, there’s never been a trace of what became of him, and probably never will be.

Stuart sent in reinforcements from all three of his brigades: the 9th and 13th Virginia, the 1st North Carolina, and squadrons of the 2nd Virginia. Custer himself had two horses shot out from under him, before his far smaller force was driven back. The wolverines of the 7th Michigan weren’t alone that day, but of the 254 Union casualties sustained on that part of the battlefield, 219 of them were from Custer’s brigade.

Stuart sent in reinforcements from all three of his brigades: the 9th and 13th Virginia, the 1st North Carolina, and squadrons of the 2nd Virginia. Custer himself had two horses shot out from under him, before his far smaller force was driven back. The wolverines of the 7th Michigan weren’t alone that day, but of the 254 Union casualties sustained on that part of the battlefield, 219 of them were from Custer’s brigade.

You must be logged in to post a comment.