HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased by the English government in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the Franklin expedition, which had disappeared into the ice pack in 1845.

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased by the English government in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the Franklin expedition, which had disappeared into the ice pack in 1845.

They never found Franklin, though they did find the long suffering crew of the HMS Investigator, hopelessly encased in ice where they had been stranded since 1850.

Three of the expedition’s ships themselves became trapped in floe ice in August 1853, including Resolute. There was no choice but to abandon ship, striking out across the ice pack in search of their supply ships. Most of them made it, despite egregious hardship, straggling into Beechey Island between May and August of the following year.

The expedition’s survivors left Beechey Island on August 29, 1854, never to return.

Meanwhile Resolute, alone and abandoned among the ice floes, continued to drift eastward at a rate of 1.5 nautical miles per day.

The American whale ship George Henry discovered the drifting Resolute on September 10, 1855, 1,200 miles from her last known position. Captain James Buddington split his crew, half of them now manning the abandoned ship. Fourteen of them sailed Resolute back to their base in Groton CT, arriving on Christmas eve.

1856 was a difficult time for American-British relations. Senator James Mason of Virginia presented a bill in Congress to fix up the Resolute, giving her back to her Majesty Queen Victoria’s government as a token of friendship between the two nations.

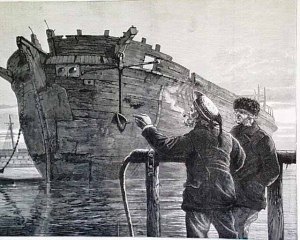

$40,000 were spent on the refit, and Resolute sailed for England later that year, Commander Henry J. Hartstene presenting her to Queen Victoria on December 13.

Resolute served in the British navy until being retired and broken up in 1879. The British government ordered at least three desks to be fashioned out of the ship’s timbers, the work being done by the skilled cabinet makers of the Chatham dockyards. The British government presented a large partner’s desk to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880. A token of gratitude for HMS Resolute’s return, 24 years earlier.

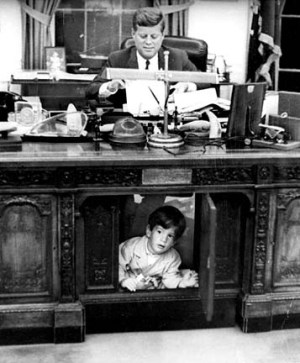

The desk, known as the Resolute Desk, has been used by almost every American President since, whether in a private study or the oval office.

FDR had a panel installed in the opening, since he was self conscious about his leg braces. It was Jackie Kennedy who brought the desk into the Oval Office. There are pictures of JFK working at the desk, while his young son JFK, Jr., played under it.

Presidents Johnson, Nixon and Ford were the only ones not to use the Resolute desk, as LBJ allowed it to leave the White House after the Kennedy assassination.

The desk spent several years in the Kennedy Library and later the Smithsonian Institute, the only time the desk has been out of the White House.

Jimmy Carter returned the Resolute Desk to the Oval Office, where it has remained through the Presidencies of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and, so far, Donald Trump.

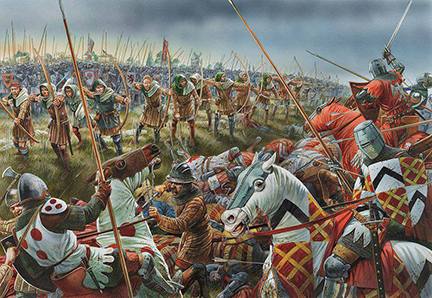

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors.

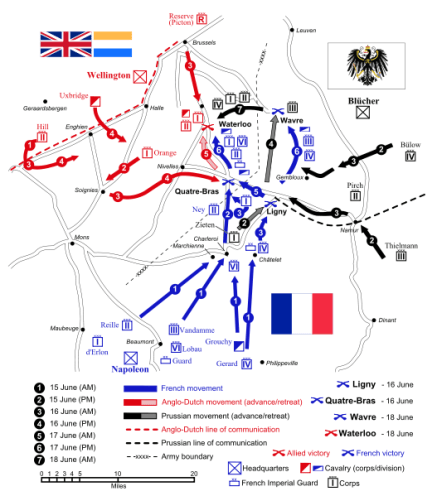

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors. The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

Several measures were taken in the 1760’s to collect these revenues. In one 12-month period, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, and deputized the Royal Navy’s Sea Officers to help enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

Several measures were taken in the 1760’s to collect these revenues. In one 12-month period, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, and deputized the Royal Navy’s Sea Officers to help enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

A few days later, a visiting minister in Boston, John Allen, used the Gaspée incident in a 2nd Baptist Church sermon. His sermon was printed seven times in four colonial cities, one of the most widely read pamphlets in Colonial British America.

A few days later, a visiting minister in Boston, John Allen, used the Gaspée incident in a 2nd Baptist Church sermon. His sermon was printed seven times in four colonial cities, one of the most widely read pamphlets in Colonial British America.

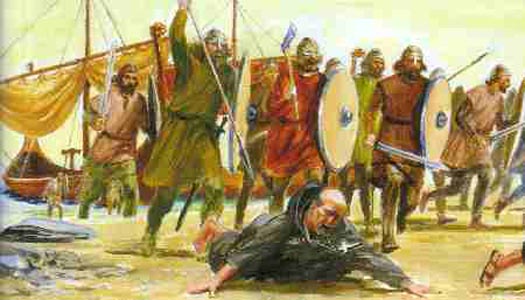

Any question you had as to their purpose would have been immediately answered, as these strangers sprinted up the beach and chased down everyone in sight. These they murdered with axe or spear, or dragged them down to the ocean and drowned them. Most of the island’s inhabitants were dead when it was over, or taken off to the ships to be sold into slavery. All of those precious objects were bagged, and tossed into the boats.

Any question you had as to their purpose would have been immediately answered, as these strangers sprinted up the beach and chased down everyone in sight. These they murdered with axe or spear, or dragged them down to the ocean and drowned them. Most of the island’s inhabitants were dead when it was over, or taken off to the ships to be sold into slavery. All of those precious objects were bagged, and tossed into the boats.

Viking travel was not all done with murderous intent; they are well known for colonizing westward as they farmed Iceland and possibly North America.

Viking travel was not all done with murderous intent; they are well known for colonizing westward as they farmed Iceland and possibly North America.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

The group reunited in 1974 to do the Holy Grail, which was filmed on location in Scotland, on a budget of £229,000. The money was raised in part by investments from musical figures like Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin backer Tony Stratton-Smith. Investors in the film wanted to cut the famous Black Knight scene, (“None shall pass”), but were eventually persuaded to keep it in the film. Good thing, the scene became second only to the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch and the Killer Rabbit. “What’s he going to do, nibble my bum?”

The group reunited in 1974 to do the Holy Grail, which was filmed on location in Scotland, on a budget of £229,000. The money was raised in part by investments from musical figures like Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin backer Tony Stratton-Smith. Investors in the film wanted to cut the famous Black Knight scene, (“None shall pass”), but were eventually persuaded to keep it in the film. Good thing, the scene became second only to the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch and the Killer Rabbit. “What’s he going to do, nibble my bum?”

Be that as it may, the cause of death was difficult to detect, the condition of the corpse close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the Man who Never Was.

Be that as it may, the cause of death was difficult to detect, the condition of the corpse close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the Man who Never Was.

The non-existent Major William Martin was buried with full military honors in the Huelva cemetery of Nuestra Señora. The headstone reads:

The non-existent Major William Martin was buried with full military honors in the Huelva cemetery of Nuestra Señora. The headstone reads:

You must be logged in to post a comment.