Deep in the heart of the Indochinese peninsula of mainland Southeast Asia lies the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, (LPDR), informally known as Muang Lao or just Laos. To the north of the country lies the Xiangkhouang Plateau, known in French as Plateau du Tran-Ninh, situated between the Luang Prabang mountain range separating Laos from Thailand, and the Annamite Range along the Vietnamese border.

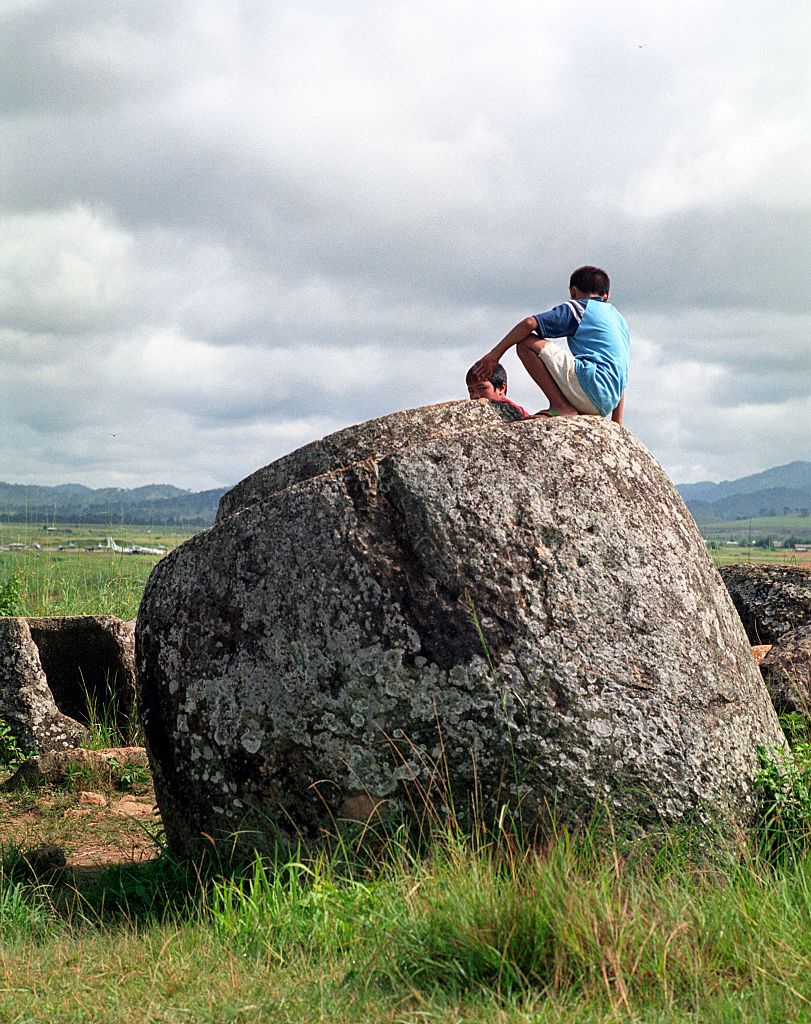

Twenty-five hundred to fifteen-hundred years ago, a now-vanished race of bronze and iron age craftsmen carved stone jars out of solid rock, ranging in size from 3 ft. to 9 ft. or more. There are thousands of these jars, located at 90 separate sites and containing between one and four hundred specimens each.

Most of these jars have carved rims but few have lids, leading researchers to speculate that lids were formed from organic material such as wood or leather.

Lao legend has it that the jars belonged to a race of giants, who chiseled them out of sandstone, granite, conglomerate, limestone and breccia to hold “lau hai”, or rice beer. More likely they were part of some ancient funerary rite, where the dead and about-to-die were inserted along with personal goods and ornaments such as beads made of glass and carnelian, cowrie shells and bronze bracelets and bells. There the deceased were “distilled” in a sitting position, later to be removed and cremated, their remains then going through secondary burial.

These “Plain of Jars” sites might be some of the oldest burial grounds in the world, but be careful if you go there. The place is the most dangerous archaeological site, on earth.

With the final French stand at Dien Bien Phu a short five months in the future, France signed the Franco–Lao Treaty of Amity and Association in 1953, establishing Laos as an independent member of the French Union.

The Laotian Civil War broke out that same year between the Communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government, becoming a “proxy war” where both sides received heavy support from the global Cold War superpowers.

Concerned about a “domino effect” in Southeast Asia, US direct foreign aid to Laos began as early as 1950. Five years later the country suffered a catastrophic rice crop failure. The CIA-operated Civil Air Transport (CAT) flew over 200 missions to 25 drop zones, delivering 1,000 tons of emergency food. By 1959, the CIA “air proprietary” was operating fixed and rotary wing aircraft in Laos, under the renamed “Air America”.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military “reunification”, with the south.

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke warned the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “If we lose Laos, we will probably lose Thailand and the rest of Southeast Asia. We will have demonstrated to the world that we cannot or will not stand when challenged”.

As the American war ramped up in Vietnam, the CIA fought a “Secret War” in Laos, in support of a growing force of Laotian highland tribesmen called the Hmong, fighting the leftist Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese communists.

Primitive footpaths had existed for centuries along the Laotian border with Vietnam, facilitating trade and travel. In 1959, Hanoi established the 559th Transportation Group under Colonel Võ Bẩm, improving these trails into a logistical system connecting the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, to the Republic of Vietnam in the south. At first just a means of infiltrating manpower, this “Hồ Chí Minh trail” through Laos and Cambodia soon morphed into a major logistical supply line.

In the last months of his life, President John F. Kennedy authorized the CIA to increase the size of the Hmong army. As many as 20,000 Highlanders took arms against far larger communist forces, acting as guerrillas, blowing up NVA supply depots, ambushing trucks and mining roads. The response was genocidal. As many as 18,000 – 20,000 Hmong tribesman were hunted down and murdered by Vietnamese and Laotian communists.

Air America helicopter pilot Dick Casterlin wrote to his parents that November, “The war is going great guns now. Don’t be misled [by reports] that I am only carrying rice on my missions as wars aren’t won by rice.”

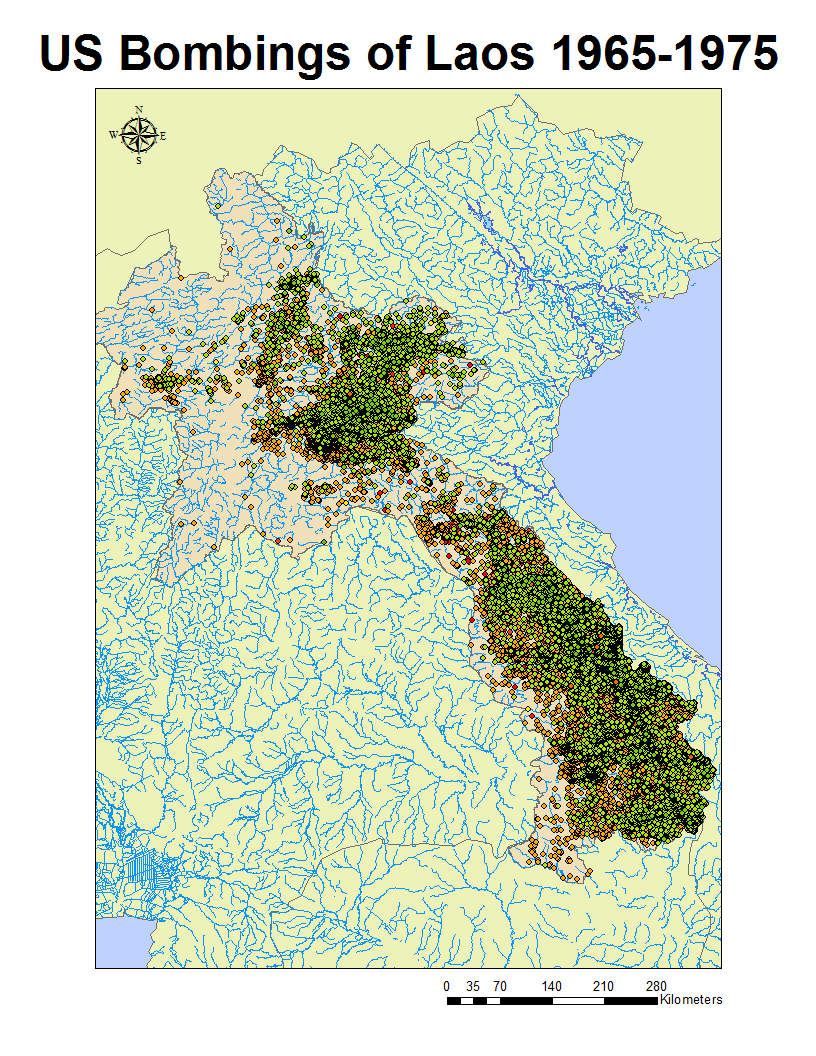

The proxy war in Laos reached a new high in 1964, in what the agency itself calls “the largest paramilitary operations ever undertaken by the CIA.” In the period 1964-’73, the US flew some 580,344 bombing missions over the Hồ Chí Minh trail and Plain of Jars, dropping an estimated 262 million bombs. Two million tons, equivalent to a B-52 bomber full every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years. More bombs than US Army Air Forces dropped in all of World War 2 making Laos the most heavily bombed country, per capita, in history.

There were all types of bombs from 3,000-pound monsters to smaller “big bombs” weighing hundreds of pounds to “cluster munitions”, canisters designed to open in flight showering the earth with 670 “bomblets” the size of a tennis ball packed with explosives and pellets. It’s estimated that 30% of these munitions failed to explode. 80 million of them, the locals call them “bombies”, set to go off with the weight of a foot, a wheel or the touch of a garden hoe and every one packing a killing radius, of 30 meters.

Since the end of the war some 20,000 civilians have been killed or maimed by unexploded ordnance, called “UXO”. Four in ten of those, are children.

Removal of such vast quantities of UXO is an effort requiring considerable time and money and no small amount of personal risk. The American Mennonite community became pioneers in the effort in the years following the war, one of the few international Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) trusted by the habitually suspicious communist leadership of the LPDR.

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

Years later, Unesco archaeologists worked to unlock the secrets of the Plain of Jars, working side by side with ordnance removal teams.

In 1996, United States Special Forces began a “train the trainer” program in UXO removal, at the invitation of the LPDR government. Even so, Western Embassy officials in the Laotian capitol of Vientiane believed that, at the current pace, total removal will take “several hundred years”.

On May 14–15, 1997, the Lao Veterans of America and others held a two day series of events honoring the contributions of ethnic Hmong and others to the American war effort, formally dedicating the Laos Memorial, at Arlington National Cemetery. It was a stunning reversal of policy, an acknowledgement of a “secret war”, the existence of which which had been denied, for years.

In 2004, bomb metal fetched 7.5 Pence Sterling, per kilogram. That’s eleven cents, for just over two pounds. Unexploded ordnance brought in 50 Pence per kilogram in the communist state, inviting young and old alike to attempt the dismantling of an endless supply of BLU-26 cluster bomblets. For seventy cents apiece.

Today, Laos is a mostly agricultural economy with rice accounting for 80% of arable land. Other crops include corn, cotton, fruit, mung beans, peanuts, soybeans, sugarcane, sweet potatoes, tobacco, and opium. Increasingly, highland farmers are turning to coffee, a more profitable crop bringing with it the expectation, that the farmer will be able to educate his children.

Profitable yes, but not without risk. The CIA’s “secret war” in Laos has been over for near a half-century. To this day cluster submunitions and other UXO kill and maim dozens, every year.

A boy digs for ant larvae to use in soup on a hillside overlooking the Plain of Jars. The area was intensively bombed and dozens of large craters can still be seen in the background.

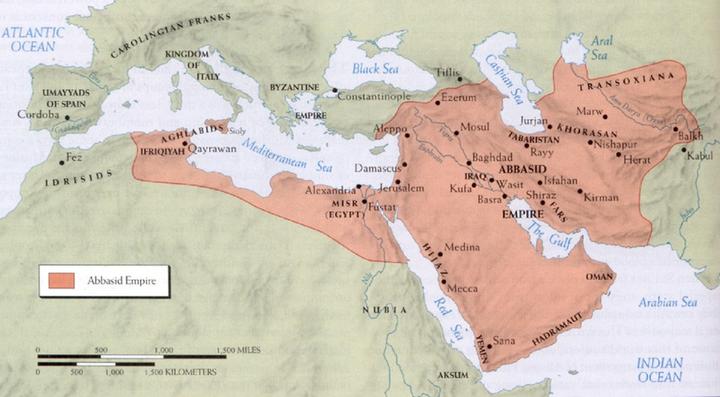

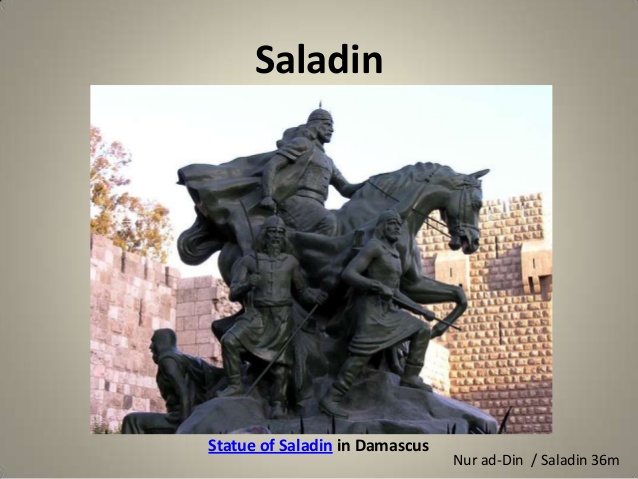

To the east lay the Great Seljuk Empire, the Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim state established in 1037 and stretching from the former Sassanid domains of modern-day Iran and Iraq to the Hindu Kush. An “appanage” or “family federation” state, the Seljuk empire was itself in flux after a series of succession contests, destined to disappear altogether in 1194.

To the east lay the Great Seljuk Empire, the Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim state established in 1037 and stretching from the former Sassanid domains of modern-day Iran and Iraq to the Hindu Kush. An “appanage” or “family federation” state, the Seljuk empire was itself in flux after a series of succession contests, destined to disappear altogether in 1194. The name derives from the Arabic “Hashashin”, meaning “those faithful to the foundation”. Marco Polo reported a story that the old man of the mountain got such fervent loyalty from his young followers, by drugging and leading them to a “paradise” of earthly delights, to which only he could bring them back. The story is probably apocryphal, there is little evidence that hashish was ever used by the Assassins’ sect. Sabbah’s followers believed him to be divine, personally selected by Allah. The man didn’t need to drug his “Fida’i” (self-sacrificing agents). He was infallible in their eyes, his every whim to be obeyed, as the literal Word of God.

The name derives from the Arabic “Hashashin”, meaning “those faithful to the foundation”. Marco Polo reported a story that the old man of the mountain got such fervent loyalty from his young followers, by drugging and leading them to a “paradise” of earthly delights, to which only he could bring them back. The story is probably apocryphal, there is little evidence that hashish was ever used by the Assassins’ sect. Sabbah’s followers believed him to be divine, personally selected by Allah. The man didn’t need to drug his “Fida’i” (self-sacrificing agents). He was infallible in their eyes, his every whim to be obeyed, as the literal Word of God. Why Sabbah would have founded such an order is unclear, if not in pursuit of his own personal and political goals. By the time of the first Crusade, 1095-1099, the Old Man of the Mountain found himself pitted against rival Muslims and invading Christian forces, alike.

Why Sabbah would have founded such an order is unclear, if not in pursuit of his own personal and political goals. By the time of the first Crusade, 1095-1099, the Old Man of the Mountain found himself pitted against rival Muslims and invading Christian forces, alike. Sometimes, a credible threat of assassination did as much an actual killing. When the new Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar rebuffed Hashashin diplomatic overtures in 1097, he awoke one morning to find a dagger stuck into the ground, next to his bed. A messenger arrived sometime later from the Old Man of the Mountain. “Did I not wish the sultan well” he said, “that the dagger which was struck in the hard ground would have been planted on your soft breast?” The tactic worked nicely. For the rest of his days, Sanjar was happy to allow the Hashashin to collect tolls from travelers in his realm. The Sultan even provided them with a pension, collected from the inhabitants of the lands they occupied.

Sometimes, a credible threat of assassination did as much an actual killing. When the new Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar rebuffed Hashashin diplomatic overtures in 1097, he awoke one morning to find a dagger stuck into the ground, next to his bed. A messenger arrived sometime later from the Old Man of the Mountain. “Did I not wish the sultan well” he said, “that the dagger which was struck in the hard ground would have been planted on your soft breast?” The tactic worked nicely. For the rest of his days, Sanjar was happy to allow the Hashashin to collect tolls from travelers in his realm. The Sultan even provided them with a pension, collected from the inhabitants of the lands they occupied. Conrad of Montferrat was elected King of Jerusalem in 1192, though he would never be crowned. Stabbed at least twice by a pair of Hashashin on April 28, on the way home, the Kurdish historian and biographer wrote “[T]he Frankish marquis, the ruler of Tyre, and the greatest devil of all the Franks, Conrad of Montferrat — God damn him! — was killed.”

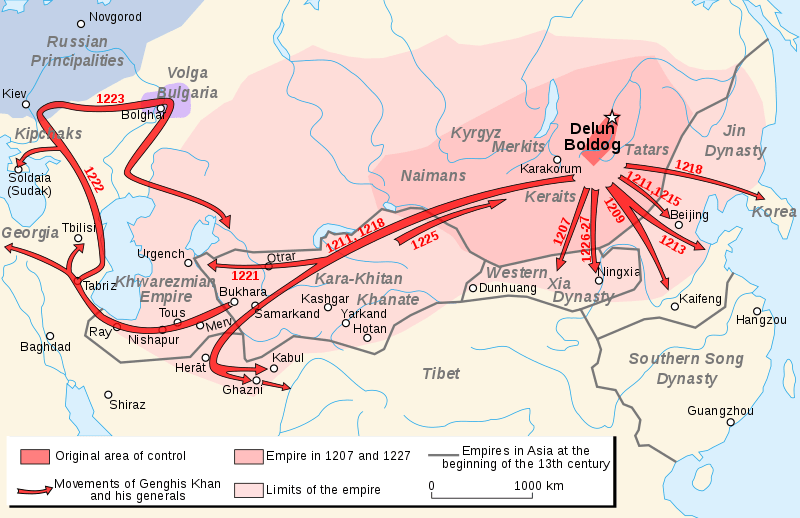

Conrad of Montferrat was elected King of Jerusalem in 1192, though he would never be crowned. Stabbed at least twice by a pair of Hashashin on April 28, on the way home, the Kurdish historian and biographer wrote “[T]he Frankish marquis, the ruler of Tyre, and the greatest devil of all the Franks, Conrad of Montferrat — God damn him! — was killed.” The Grand Master of the Assassins dispatched his killers to Karakorum in the early 1250s, to murder the grandson of Genghis Khan, the Great Khan of the “Golden Horde”, Möngke. It was a Bad idea.

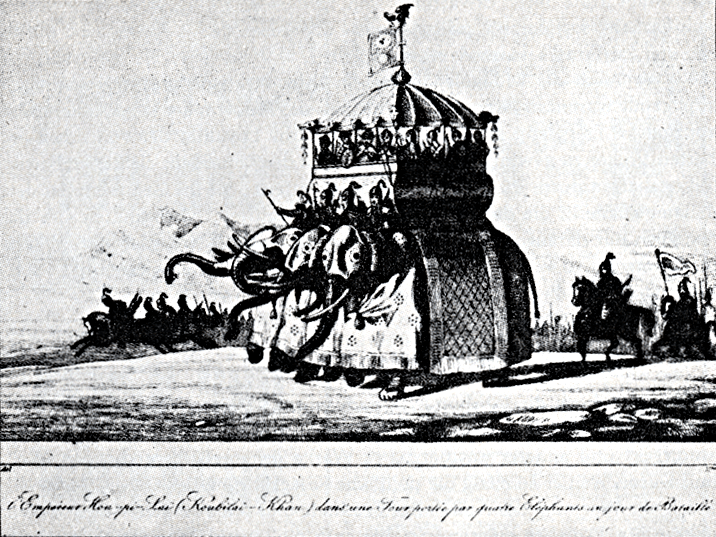

The Grand Master of the Assassins dispatched his killers to Karakorum in the early 1250s, to murder the grandson of Genghis Khan, the Great Khan of the “Golden Horde”, Möngke. It was a Bad idea. Hulagu went on to subjugate the 5+ million Lurs people of western and southwestern Iran, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, the Ayyubid state of Damascus, and the Bahri Mamluke Sultanate of Egypt. Mongol and Muslim accounts alike, agree that the Caliph of Baghdad was rolled up in a Persian rug, whereupon the horsemen of Hulagu rode over him. Mongols believed that the earth was offended if touched by royal blood.

Hulagu went on to subjugate the 5+ million Lurs people of western and southwestern Iran, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, the Ayyubid state of Damascus, and the Bahri Mamluke Sultanate of Egypt. Mongol and Muslim accounts alike, agree that the Caliph of Baghdad was rolled up in a Persian rug, whereupon the horsemen of Hulagu rode over him. Mongols believed that the earth was offended if touched by royal blood.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

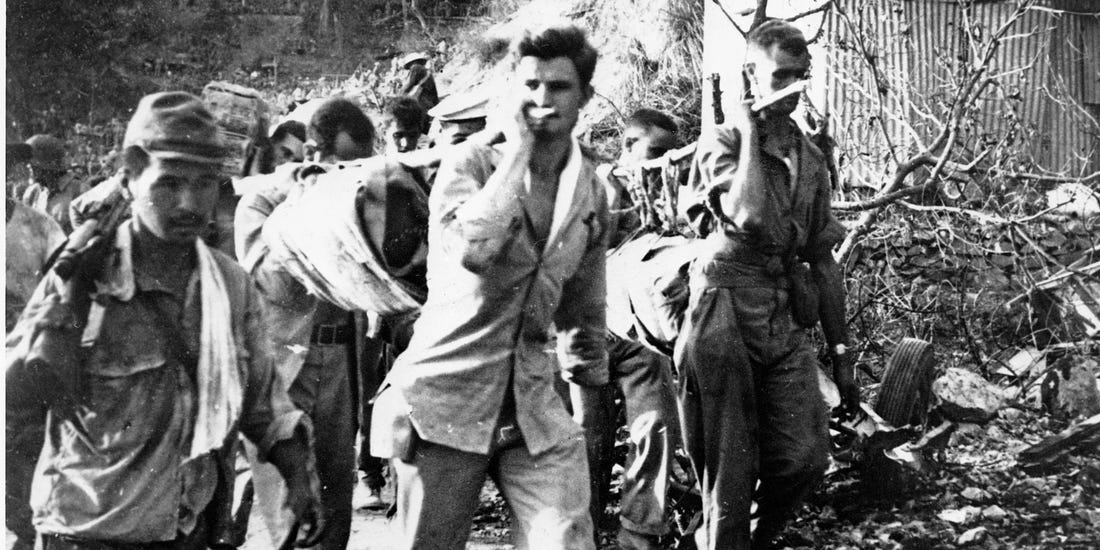

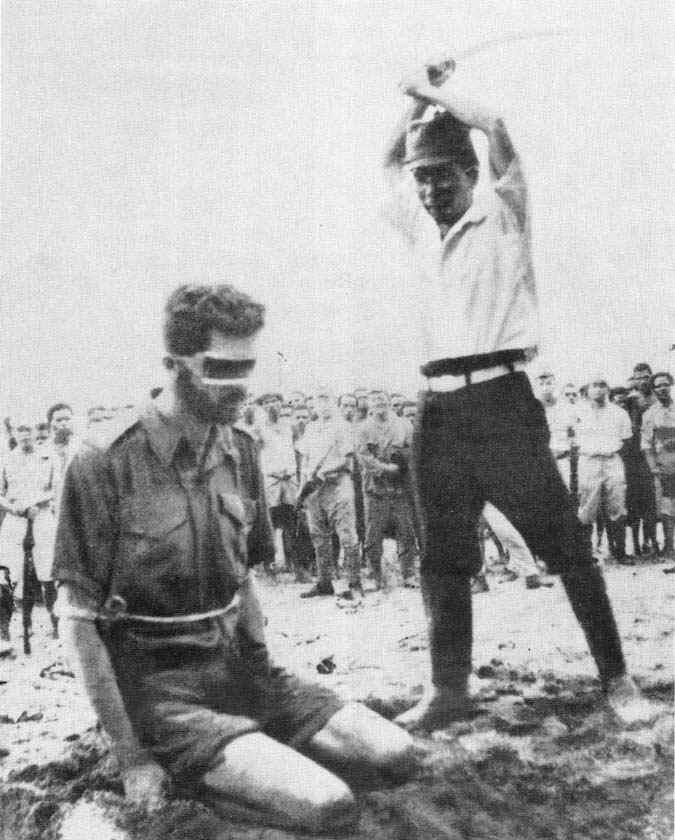

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w

Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects. Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

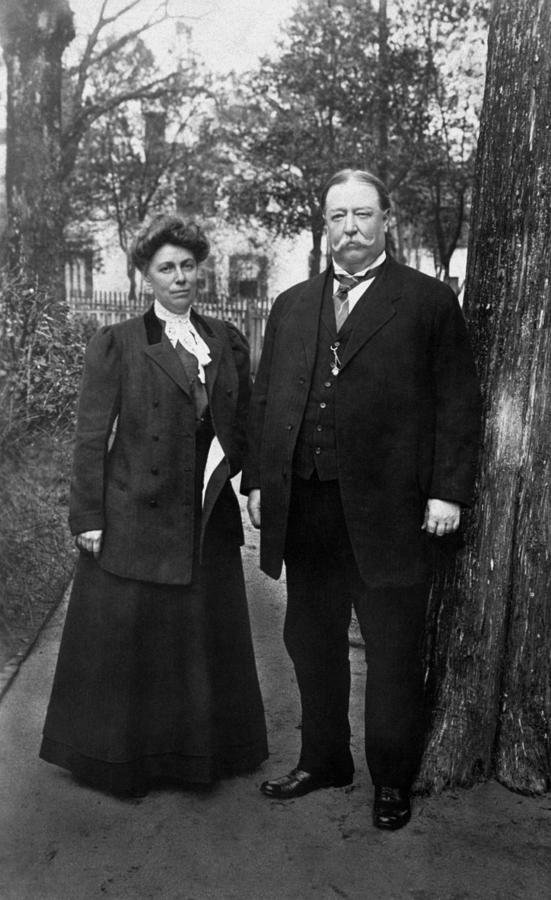

Frequent visits with her brother led to a passionate interest in all things Japanese, most especially the Japanese cherry, Prunus serrulata, commonly known as the Sakura. The Japanese blossoming cherry tree. She called them “the most beautiful thing in the world”.

Frequent visits with her brother led to a passionate interest in all things Japanese, most especially the Japanese cherry, Prunus serrulata, commonly known as the Sakura. The Japanese blossoming cherry tree. She called them “the most beautiful thing in the world”.

On March 27, 1912, the Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese ambassador to the United States joined First Lady Helen Taft, in planting two Japanese Yoshino cherry trees on the bank of the Potomac River, near the Jefferson memorial.

On March 27, 1912, the Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese ambassador to the United States joined First Lady Helen Taft, in planting two Japanese Yoshino cherry trees on the bank of the Potomac River, near the Jefferson memorial.

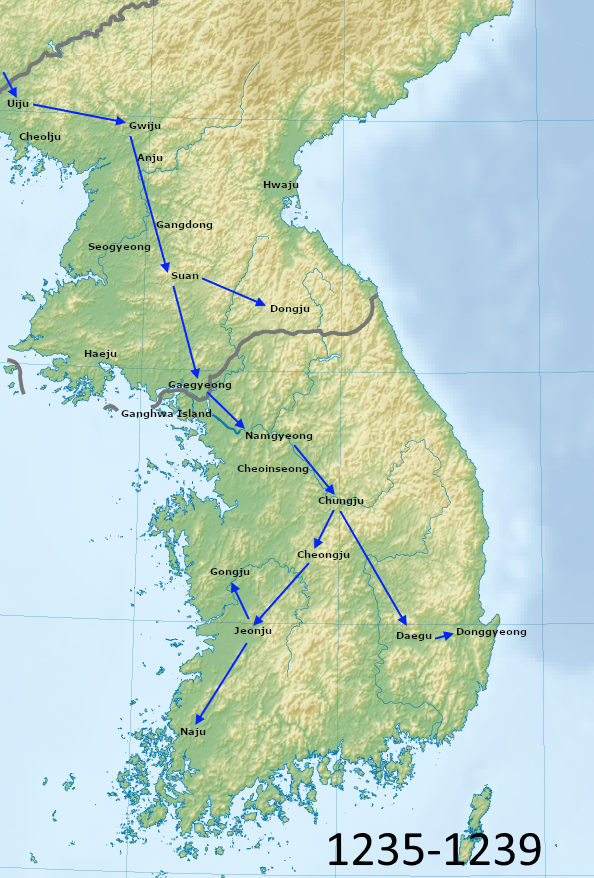

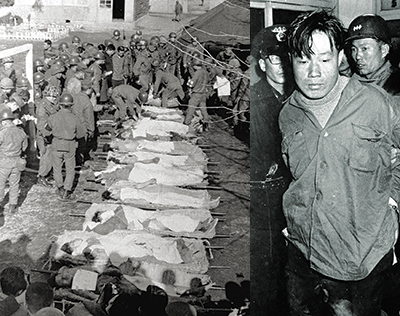

On January 17, 1968, Unit 124 infiltrated the 2½ mile demilitarized zone (DMZ), cutting the wire and entering South Korea. Their mission was to assassinate ROK President Park Chung-hee in his home, the Executive Mansion equivalent to the United States’ own White House, the “Pavilion of Blue Tiles” known as “Blue House”.

On January 17, 1968, Unit 124 infiltrated the 2½ mile demilitarized zone (DMZ), cutting the wire and entering South Korea. Their mission was to assassinate ROK President Park Chung-hee in his home, the Executive Mansion equivalent to the United States’ own White House, the “Pavilion of Blue Tiles” known as “Blue House”.

29 commandos were killed or committed suicide. One escaped, back to North Korea. Only one, Kim Shin-jo, was captured alive.

29 commandos were killed or committed suicide. One escaped, back to North Korea. Only one, Kim Shin-jo, was captured alive.

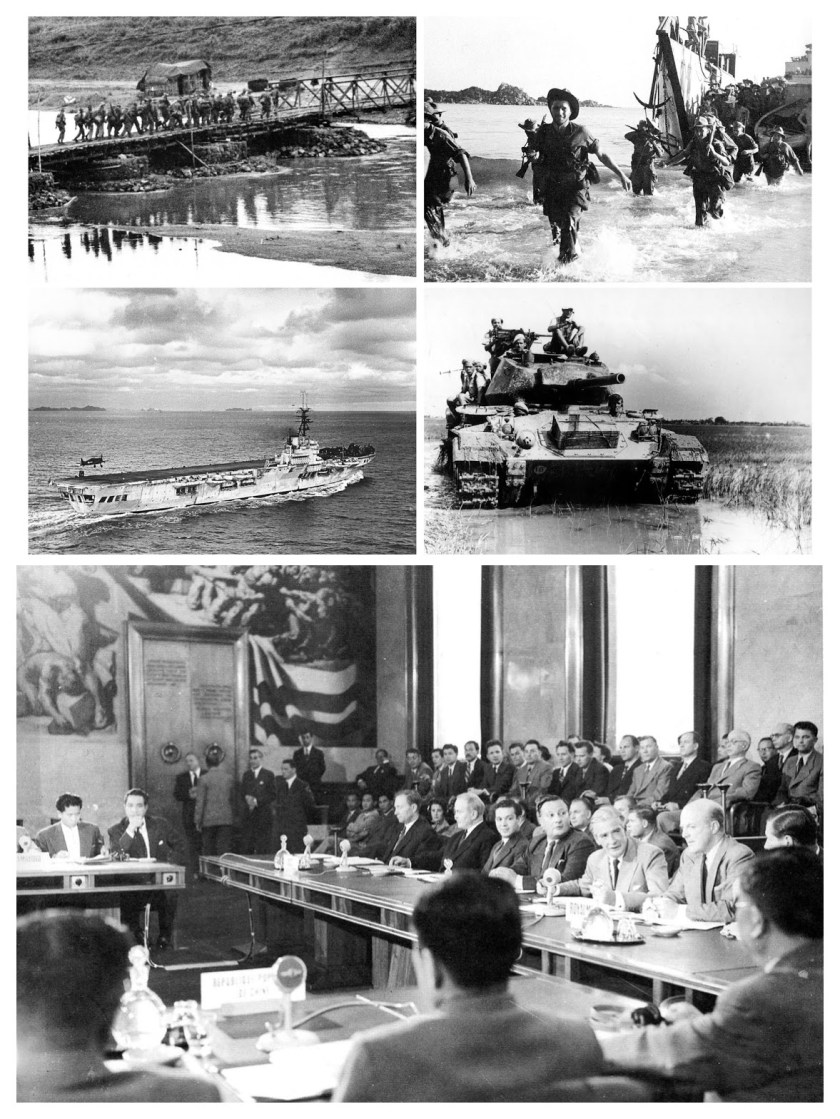

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities. The war went poorly for the Colonial power. By 1952 the French were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”.

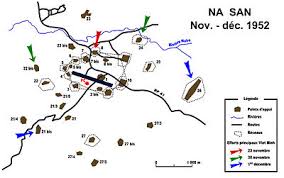

The war went poorly for the Colonial power. By 1952 the French were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”. In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted to a heavily fortified base.

In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted to a heavily fortified base. The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

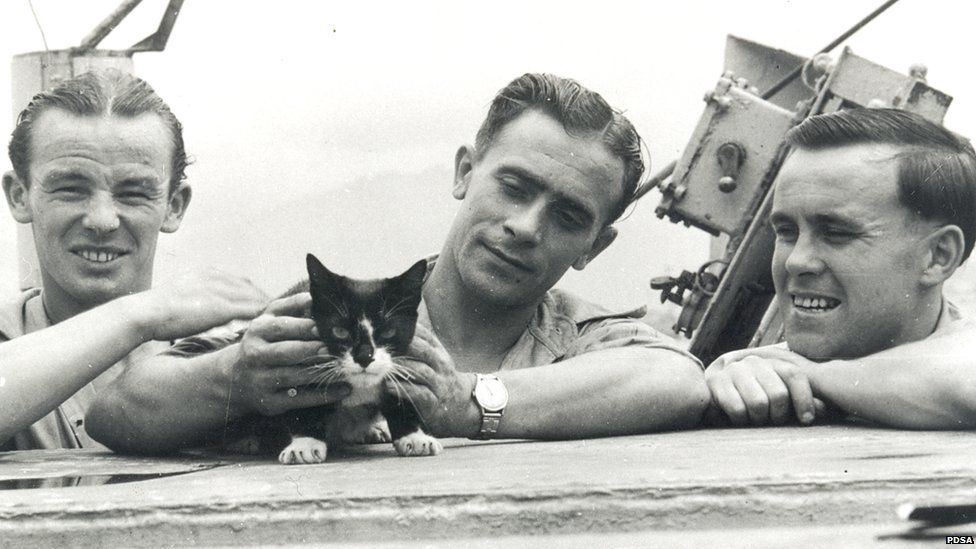

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.