In 1915, Albert Marr lived with his family and his Chacma baboon, Jackie, on Cheshire Farm, on the outskirts of Pretoria, South Africa. The Great War had begun a year earlier, when Marr was sworn into the 3rd (Transvaal) Regiment of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade, in August of that year. He was now Private Albert Marr, #4927.

Private Marr asked for and received permission to bring Jackie along with him. It wasn’t long before the monkey became the official Regimental Mascot.

Private Marr asked for and received permission to bring Jackie along with him. It wasn’t long before the monkey became the official Regimental Mascot.

Jackie drew rations like any other soldier, eating at the mess table, using his knife and fork and washing it all down with his own drinking basin.

He drilled and marched with his company in a special uniform and cap, complete with buttons, regimental badges, and a hole for his tail.

Jackie entertained the men during quiet periods, lighting their pipes and cigarettes and saluting officers as they passed on their rounds. He learned to stand at ease when ordered, placing his feet apart and hands behind his back, regimental style.

These two inseparable buddies, Albert Marr and Jackie, first saw combat during the Senussi Campaign in North Africa. Albert took a bullet in the shoulder at the Battle of Agagia on February 26, 1916, while the monkey, beside himself with agitation, licked the wound and did everything he could to comfort the stricken man. It was this incident more than any other that marked Jackie’s transformation from pet and mascot, to a comrade to the men of the regiment.

Jackie would accompany Albert at night when he was on guard duty. Marr soon learned to trust Jackie’s keen eyesight and acute hearing. The monkey was almost always first to know about enemy movements or impending attack. He would give early warning with a series of sharp barks, or by pulling on Marr’s tunic.

The pair went through the nightmare of Delville Wood together, early in the Somme campaign, when the First South African Infantry held their position despite 80% casualties. The pair experienced the nightmare of mud that was Passchendaele, and the desperate fighting at Kemmel Hill. The two were at Belleau Wood, a primarily American operation, where Marine Captain Lloyd Williams of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, was informed that he was surrounded by Germans. “Retreat?” Williams retorted, “hell, we just got here.”

Throughout all of it, Albert Marr and Jackie had come through WWI mostly unscathed. That all changed in April, 1918.

The South African Brigade was being heavily shelled as it withdrew through the West Flanders region of Belgium. Jackie was frantically trying to build a wall of stones around himself, a shelter from flying shrapnel, while shells were bursting all around. A jagged piece of shrapnel wounded Jackie in the arm and another all but amputated the animal’s leg. He refused to be carried off by the stretcher-bearers, trying instead to finish his wall, hobbling around on what had once been his leg.

Lt. Colonel R. N. Woodsend of the Royal Medical Corps described the scene: “It was a pathetic sight; the little fellow, carried by his keeper, lay moaning in pain, the man crying his eyes out in sympathy, ‘You must do something for him, he saved my life in Egypt. He nursed me through dysentery’. The baboon was badly wounded, the left leg hanging with shreds of muscle, another jagged wound in the right arm. We decided to give the patient chloroform and dress his wounds…It was a simple matter to amputate the leg with scissors and I cleaned the wounds and dressed them as well as I could. He came around as quickly as he went under. The problem then was what to do with him. This was soon settled by his keeper: ‘He is on army strength’. So, duly labelled, number, name, ATS injection, nature of injuries, etc. he was taken to the road and sent by a passing ambulance to the Casualty Clearing Station”.

As the war drew to a close, Jackie was promoted to the rank of Corporal, and given a medal for bravery. Possibly the only monkey in history, ever to be so honored.

On his arm he wore a gold wound stripe, and three blue service chevrons, one for each of his three years’ front line service.

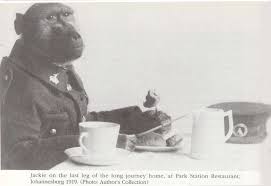

After the pair arrived home, Jackie became the center of attention at a parade officially welcoming the 1st South African Regiment home.

On July 31, 1920, Jackie received the Pretoria Citizen’s Service Medal, at the Peace Parade in Church Square, Pretoria.

Jackie died as the result of a fire, which destroyed the Marr family farmhouse in May 1921. Albert Marr passed away in 1973, at the age of 84. Marr had missed his battle buddy Jackie, for all the days in-between.

During the landing phase, private Rowell and Chips were pinned down by an Italian machine gun team. The dog broke free from his handler, running across the beach and jumping into the pillbox. Chips attacked the four Italians manning the machine gun, single-handedly forcing their surrender to American troops. The dog sustained a scalp wound and powder burns in the process, demonstrating that they had tried to shoot him during the brawl. In the end, the score was Chips 4, Italians Zero. He helped to capture ten more later that same day.

During the landing phase, private Rowell and Chips were pinned down by an Italian machine gun team. The dog broke free from his handler, running across the beach and jumping into the pillbox. Chips attacked the four Italians manning the machine gun, single-handedly forcing their surrender to American troops. The dog sustained a scalp wound and powder burns in the process, demonstrating that they had tried to shoot him during the brawl. In the end, the score was Chips 4, Italians Zero. He helped to capture ten more later that same day.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

“Sallie was a lady,

“Sallie was a lady,

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

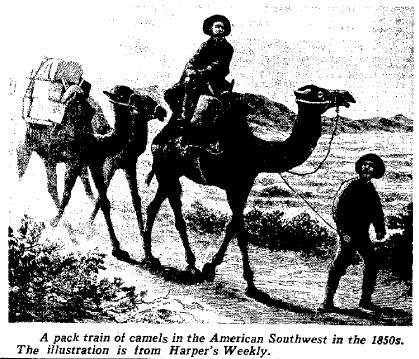

Some of Camp Verde’s camels were sold off, one was pushed over a cliff by frustrated cavalrymen. Most were simply turned loose to fend for themselves. Their fates are mostly unknown, except for one who made his way to Mississippi in 1863, where he was taken into service with the 43rd Infantry Regiment. “Douglas the Confederate Camel” was a common sight throughout the siege of Vicksburg, until being shot and killed by a Union sharpshooter. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bevier of the 5th Regiment, Missouri Confederate Infantry was furious, enlisting six of his best snipers to rain down hell on Douglas’ killer. Bevier later said of the Federal soldier “I refused to hear his name, and was rejoiced to learn that he had been severely wounded.”

Some of Camp Verde’s camels were sold off, one was pushed over a cliff by frustrated cavalrymen. Most were simply turned loose to fend for themselves. Their fates are mostly unknown, except for one who made his way to Mississippi in 1863, where he was taken into service with the 43rd Infantry Regiment. “Douglas the Confederate Camel” was a common sight throughout the siege of Vicksburg, until being shot and killed by a Union sharpshooter. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bevier of the 5th Regiment, Missouri Confederate Infantry was furious, enlisting six of his best snipers to rain down hell on Douglas’ killer. Bevier later said of the Federal soldier “I refused to hear his name, and was rejoiced to learn that he had been severely wounded.” men to return. The pair returned that night and found the body of the other woman by the stream. She’d been trampled almost flat, with huge, cloven hoof prints in the mud around her body and a few red hairs in the brush.

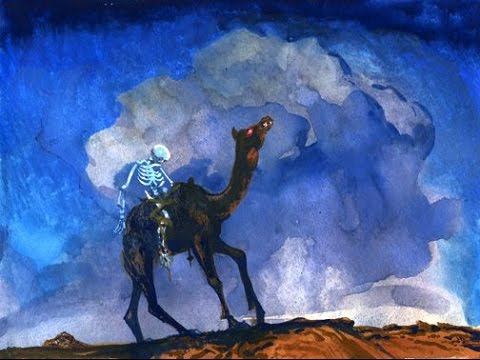

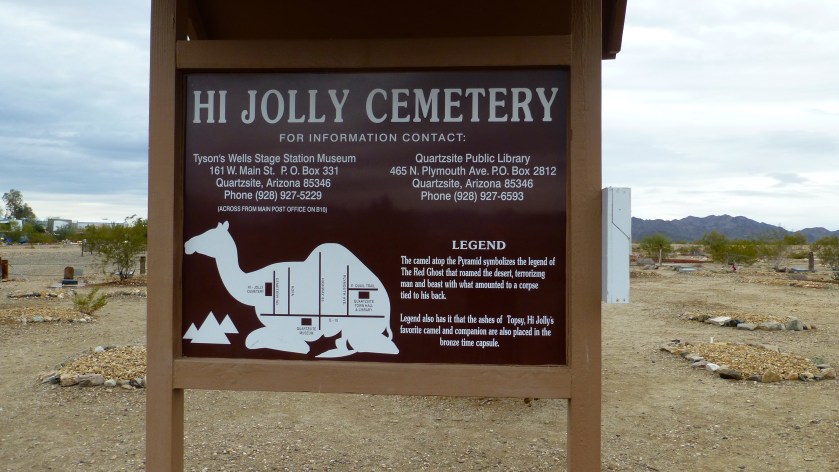

men to return. The pair returned that night and found the body of the other woman by the stream. She’d been trampled almost flat, with huge, cloven hoof prints in the mud around her body and a few red hairs in the brush. There were further incidents over the next year, mostly at prospector camps. A cowboy near Phoenix came upon the Red Ghost while eating grass in a corral. Cowboys seem to think they can rope anything with hair on it, and this guy was no exception. He lashed the rope onto the pommel of his saddle, and tossed it over the camel’s head. The angry beast turned and charged, knocking horse and rider to the ground. As the camel galloped off, the astonished cowboy could clearly see the skeletal remains of a man lashed to its back.

There were further incidents over the next year, mostly at prospector camps. A cowboy near Phoenix came upon the Red Ghost while eating grass in a corral. Cowboys seem to think they can rope anything with hair on it, and this guy was no exception. He lashed the rope onto the pommel of his saddle, and tossed it over the camel’s head. The angry beast turned and charged, knocking horse and rider to the ground. As the camel galloped off, the astonished cowboy could clearly see the skeletal remains of a man lashed to its back.

You must be logged in to post a comment.