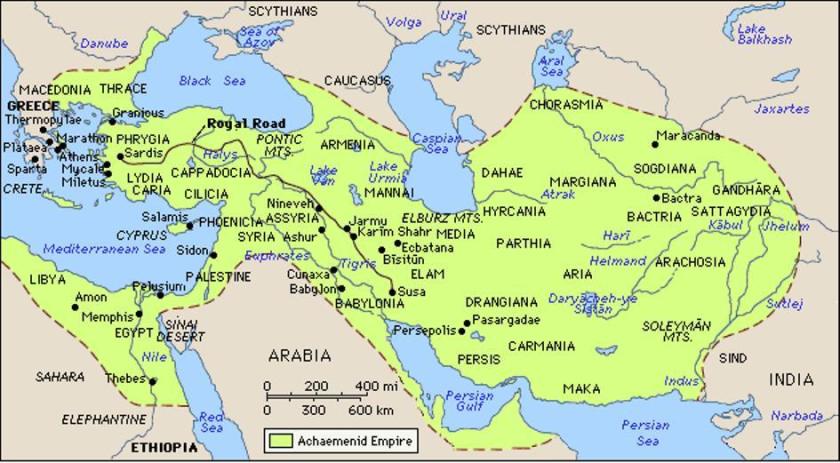

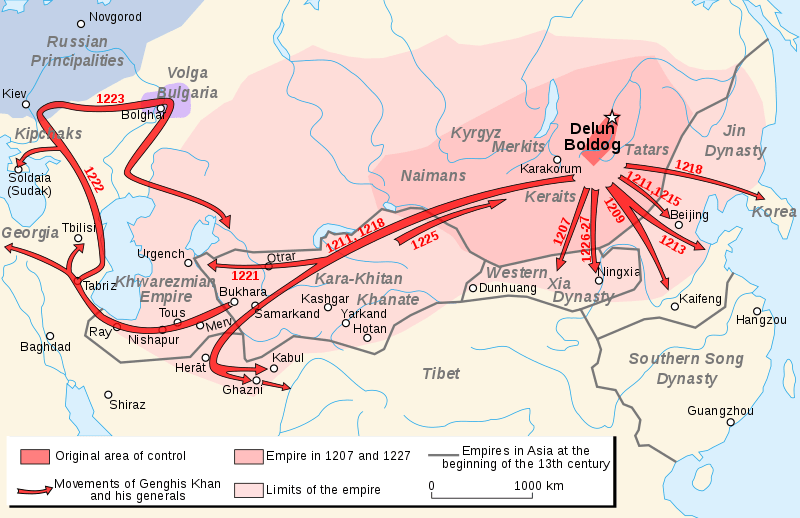

200 years before the classical age of Greece, King Darius I, third King of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, ruled over an area stretching from North Africa to the Indian sub-continent, from Kazakhstan to the Arabian Peninsula. Several Anatolian coastal polities rebelled in 499BC, with support and encouragement from the mainland city states of Athens and Eritrea.

This “Ionian Revolt” lasted until 493BC. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the Greeks had exposed themselves to the wrath of Darius. Herodotus records that, every night before dinner, Darius required one of his servants three times, to say to him “Master, remember the Athenians“.

The Persian “King of Kings” sent emissaries to the Greek city states, demanding gifts of earth and water, signifying Darius’ dominion over all the land and sea. Most capitulated, but Athens put Darius’ emissaries on trial and executed them. Sparta didn’t bother with a trial. They threw Darius’ ambassadors down a well. “There is your earth”, they said. “There is your water”.

Athens and Sparta were now effectively at war with the Persian Empire.

2511 years ago, Darius sent an amphibious expedition to the Aegean, attacking Naxos and sacking Eritrea. A force of some 600 triremes commanded by the Persian General Datis and Darius’ own brother Artaphernes then sailed for Attica, fetching up in a small bay near the town of Marathon, about 25 miles from Athens.

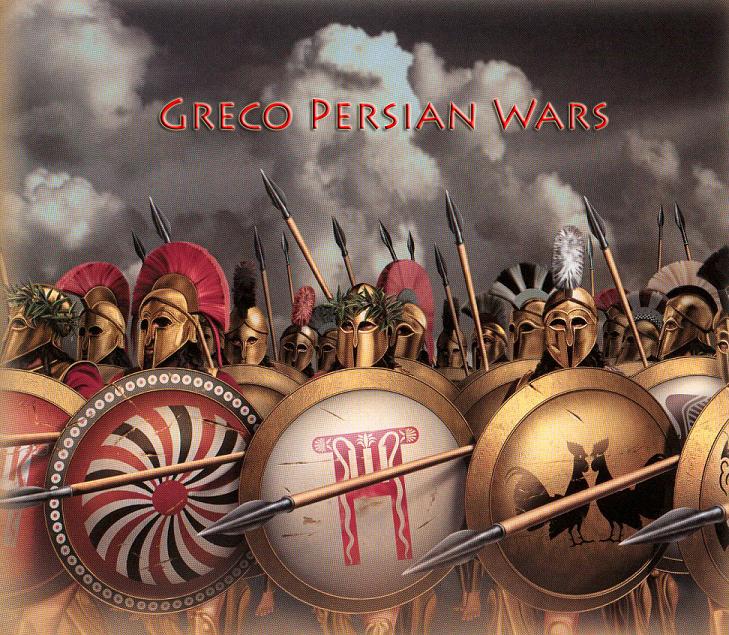

An army of 9,000-10,000 hoplites (armored infantry) marched out of Athens under the leadership of ten Athenian Strategoi (Generals), to face the 25,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry of the Persians. The Athenian force was soon joined by a full muster of 1,000 Plataean hoplites, while Athens’ swiftest runner Pheidippides was dispatched to Lacedaemon, for help.

The festival of Carneia was underway at this time, a sacrosanct religious occasion during which the Lacedaemonian (Spartan) army would not fight, under any circumstance. Sparta would be unavailable until the next full moon, on September 9. With 136 miles to Marathon, Spartan reinforcement was unlikely to arrive for the next week or more.

The Athenian force arrived at the Plain of Marathon around September 7, blocking the Persian route into the interior.

Facing a force more than twice as large their own, Greek Generals split 5 to 5 whether to risk battle.

A “Polemarch” is an Athenian civil dignitary, with full voting rights in military matters. General Miltiades, who enjoyed a degree of deference due to his experience fighting Persians, went to the Polemarch Callimachus, for the deciding vote.

The stakes are difficult to overstate. Arguably, the future of Western Civilization hung in the balance.

With Athens behind them now defenseless, its every warrior here on the plain of Marathon, Miltiades spoke. ‘With you it rests, Callimachus, either to bring Athens to slavery, or, by securing her freedom, to be remembered by all future generations…We generals are ten in number, and our votes are divided. Half of us wish to engage, half to avoid a combat. Now, if we do not fight, I look to see a great disturbance at Athens which will shake men’s resolutions, and then I fear they will submit themselves. But, if we fight the battle…we are well able to overcome the enemy.’

With less than a mile between them, the two armies had faced one another for five days and five nights. On September 12, 490BC, the order went down the Athenian line. “At them!”

Advertisementshttps://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.3/html/safeframe.htmlREPORT THIS AD

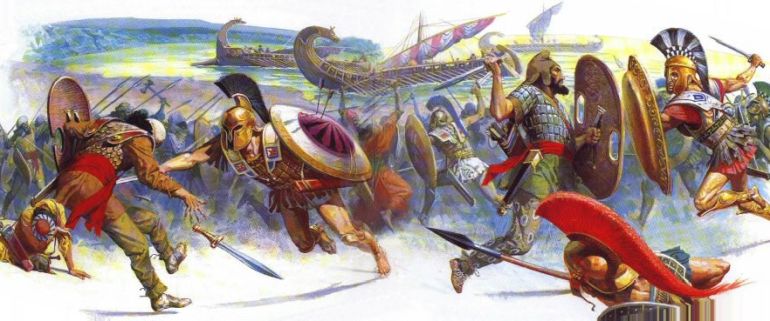

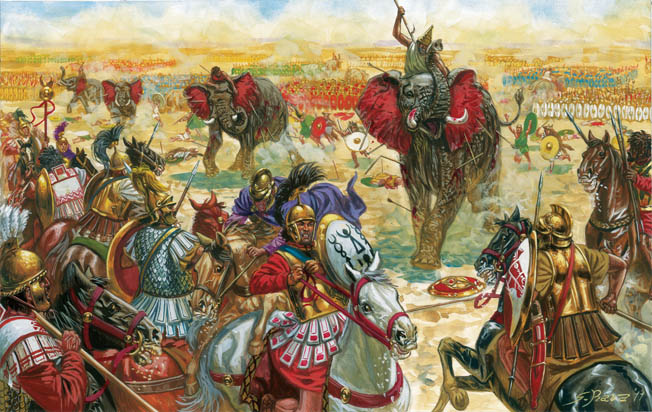

Weighed down with 70lbs per man of bronze and leather armor, the Greek line likely marched out to 200 yards, the effective range of Persian archers. Greek heavy infantry closed the last 200 meters at a dead run, the first time a Greek army had fought that way.

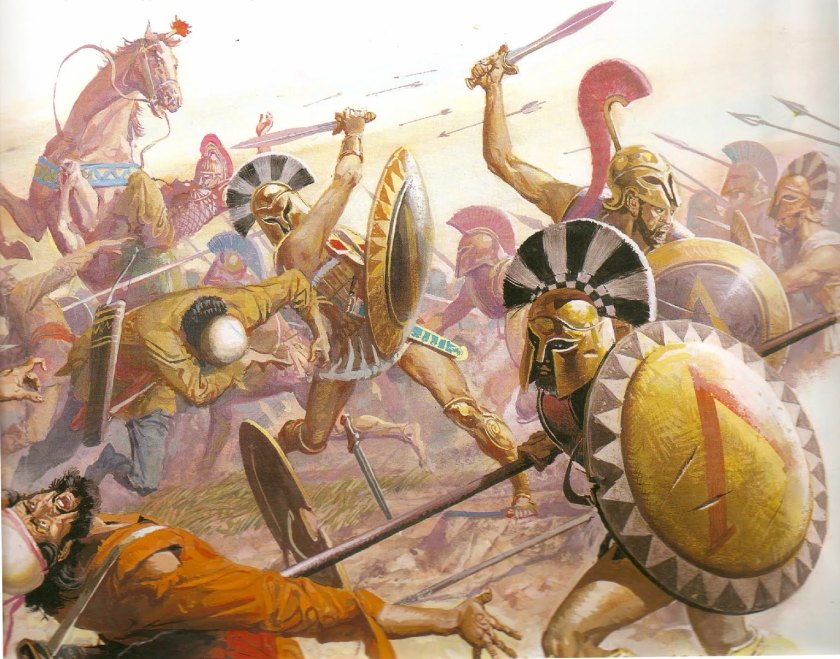

Persian shafts flew by the thousands, yet the heavy armor and wooden shields of the hoplite formation, held. Bristling with arrows yet seemingly unhurt, the Greek phalanx smashed into the Persian adversary, like an NFL front line into an ‘Antifa” demonstration.

Tom Holland, author of Persian Fire, describes the impact. “The enemy directly in their path … realized to their horror that [the Athenians], far from providing the easy pickings for their bowmen, as they had first imagined, were not going to be halted … The impact was devastating. The Athenians had honed their style of fighting in combat with other phalanxes, wooden shields smashing against wooden shields, iron spear tips clattering against breastplates of bronze … in those first terrible seconds of collision, there was nothing but a pulverizing crash of metal into flesh and bone; then the rolling of the Athenian tide over men wearing, at most, quilted jerkins for protection, and armed, perhaps, with nothing more than bows or slings. The hoplites’ ash spears, rather than shivering … could instead stab and stab again, and those of the enemy who avoided their fearful jabbing might easily be crushed to death beneath the sheer weight of the advancing men of bronze“.

Advertisementshttps://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.3/html/safeframe.htmlREPORT THIS AD

Darius’ force was routed, driven across the beach and onto waiting boats. 6,400 Persians lay dead in the sand, an unknown number were chased into coastal swamps, and drowned. Athens lost 192 men that day, Plataea, 11.

In the popular telling of this story, Pheidippides ran the 25 miles to Athens and announced the victory with the single word “Nenikēkamen!” (We’ve won!”), and dropped dead.

That version first appeared in the writings of Plutarch, some 500 years later. It made for a good story for the first Olympic promoters, too, back in 1896, but that’s not the way it happened.

Herodotus of Halicarnassus, described by no less a figure than Cicero as the “Father of History”, tells us that Pheidippides was already spent. No wonder. The man had run 140 miles from Athens to Lacedaemon, to ask for Spartan assistance.

Despite the exhaustion of battle and the weight of all that armor, the Athenian host marched the 25 miles back home, arriving in time to head off the Persian fleet. The Spartans arrived at Marathon the following day, having covered 136 miles in three days.

Though a great victory for the Greeks, Darius’ loss at Marathon barely put a dent in the vast resources of the Achaemenid Empire. The Persian King, would return.

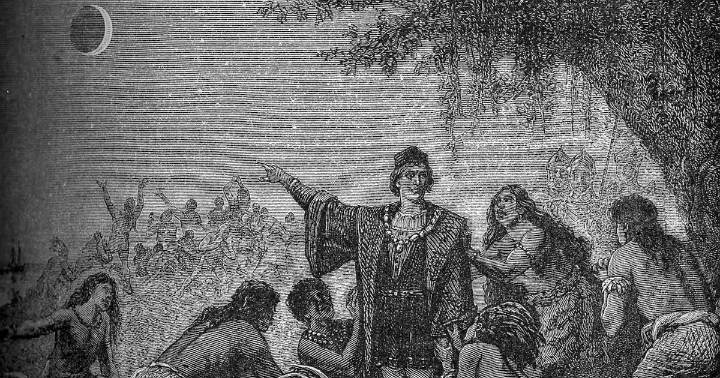

Dating the historical events of antiquity with any kind of accuracy can be problematic, but not this one. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the mathematician and astronomer Thales of Miletus predicted the eclipse in a year when the Medians and the Lydians were at war. The “solar clock” can be run backward as well as forward. Thanks to Herodotus, it’s possible to calculate the date with precision. May 28 is one of the cardinal dates from which other dates in antiquity, may be calculated.

Dating the historical events of antiquity with any kind of accuracy can be problematic, but not this one. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the mathematician and astronomer Thales of Miletus predicted the eclipse in a year when the Medians and the Lydians were at war. The “solar clock” can be run backward as well as forward. Thanks to Herodotus, it’s possible to calculate the date with precision. May 28 is one of the cardinal dates from which other dates in antiquity, may be calculated. Predicting a solar eclipse isn’t the same as predicting an eclipse of the moon. The calculations are far more difficult. When the moon passes through the shadow of the sun, the event can be seen over half the planet, the total eclipse phase lasting over an hour. In a solar eclipse, the shadow of the moon occupies only a narrow path. The total eclipse phase at any given point, lasts only about 7½ minutes.

Predicting a solar eclipse isn’t the same as predicting an eclipse of the moon. The calculations are far more difficult. When the moon passes through the shadow of the sun, the event can be seen over half the planet, the total eclipse phase lasting over an hour. In a solar eclipse, the shadow of the moon occupies only a narrow path. The total eclipse phase at any given point, lasts only about 7½ minutes. Be that as it may, for the first time in history a full eclipse of the sun had been predicted beforehand. The Battle of Halys marked the first time in history, that a war was ended when day turned to night. Aylattes, King of Lydia and Cyaxares, King of the Medes, put down their weapons and declared a truce and their armies, followed suit. With help from the kings of Cilicia and Babylon, the two sides negotiated a more permanent treaty.

Be that as it may, for the first time in history a full eclipse of the sun had been predicted beforehand. The Battle of Halys marked the first time in history, that a war was ended when day turned to night. Aylattes, King of Lydia and Cyaxares, King of the Medes, put down their weapons and declared a truce and their armies, followed suit. With help from the kings of Cilicia and Babylon, the two sides negotiated a more permanent treaty.

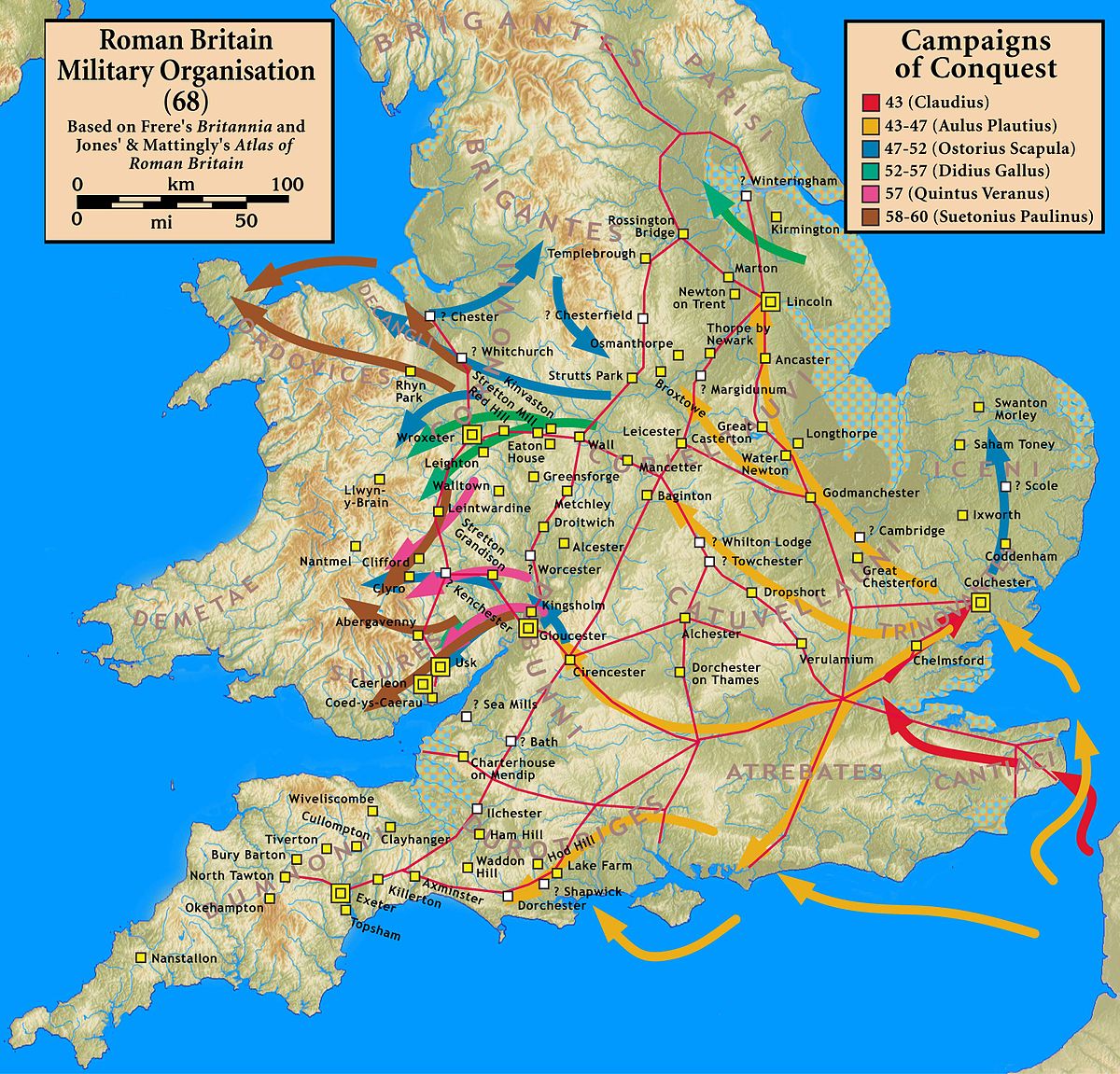

In the Roman imagination, Britain was a faraway and exotic place, a misty, forested land inhabited by fierce, blue painted warriors.

In the Roman imagination, Britain was a faraway and exotic place, a misty, forested land inhabited by fierce, blue painted warriors. Militarily, there was no reason to attack the British home isles. The channel itself formed as fine a protector of the western flank, as could be hoped for.

Militarily, there was no reason to attack the British home isles. The channel itself formed as fine a protector of the western flank, as could be hoped for.

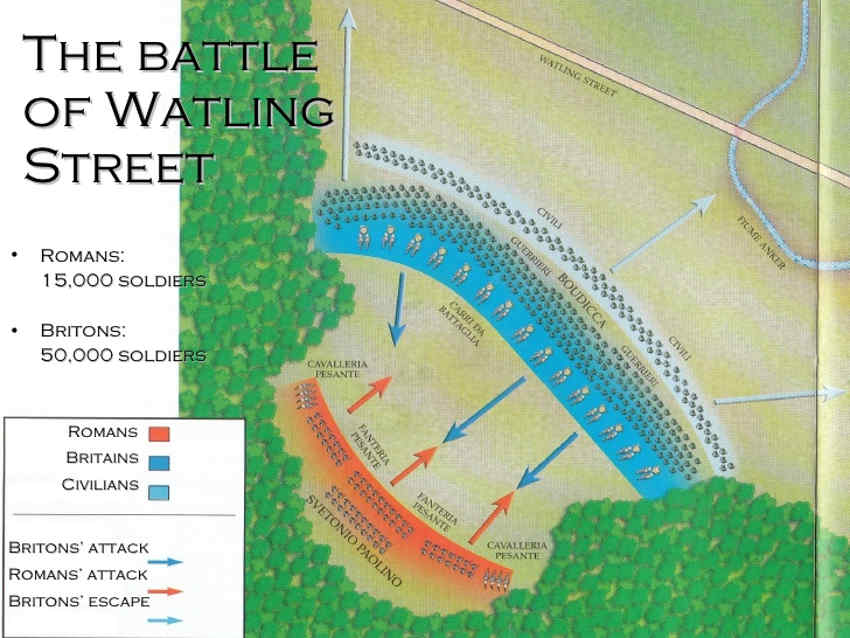

Apoplectic with rage and determined to avenge her family, Boudicca was not a woman to be trifled with. She led the Iceni, the Trinovantes and others among the Celtic, pre-Roman peoples of Britain, in a full-scale, bloody revolt.

Apoplectic with rage and determined to avenge her family, Boudicca was not a woman to be trifled with. She led the Iceni, the Trinovantes and others among the Celtic, pre-Roman peoples of Britain, in a full-scale, bloody revolt. For the Celtic peoples, the hour of payback had arrived. For the seizure of lands to provide estates for Roman veterans to their own forced labor in building the Temple of Claudius to the sudden recall of loans and destruction of estates and properties. The Roman historian Tacitus writes of the last stand at the Temple of Claudius: “In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked“.

For the Celtic peoples, the hour of payback had arrived. For the seizure of lands to provide estates for Roman veterans to their own forced labor in building the Temple of Claudius to the sudden recall of loans and destruction of estates and properties. The Roman historian Tacitus writes of the last stand at the Temple of Claudius: “In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked“. Outnumbered 23 to 1, the 10,000 strong Roman legion was battle hardened, well-equipped and disciplined, facing off against a mob of nearly a quarter-million unarmored, poorly disciplined individuals.

Outnumbered 23 to 1, the 10,000 strong Roman legion was battle hardened, well-equipped and disciplined, facing off against a mob of nearly a quarter-million unarmored, poorly disciplined individuals. What must it look like, when 230,000 screaming warriors charge a fixed force of 10,000 disciplined soldiers. First came the Pila, the Roman javelins tearing into the tightly packed front, of the adversary. Then the Legion advanced, shields out front with the short swords, the long swords and farm implements of the Celts unable to move in the crush of humanity. The wedge formation advanced unbroken, slaughtering all who came before it as a scythe before the grass. The turning and the attempt to flee, only to be boxed in by their own tightly packed crescent formed wagon train.

What must it look like, when 230,000 screaming warriors charge a fixed force of 10,000 disciplined soldiers. First came the Pila, the Roman javelins tearing into the tightly packed front, of the adversary. Then the Legion advanced, shields out front with the short swords, the long swords and farm implements of the Celts unable to move in the crush of humanity. The wedge formation advanced unbroken, slaughtering all who came before it as a scythe before the grass. The turning and the attempt to flee, only to be boxed in by their own tightly packed crescent formed wagon train. 80,000 of Boudicca’s men lay dead before the slaughter was ended, against 400 dead Romans. Queen Boudicca poisoned herself according to Tacitus, Cassius Dio claims she became ill.

80,000 of Boudicca’s men lay dead before the slaughter was ended, against 400 dead Romans. Queen Boudicca poisoned herself according to Tacitus, Cassius Dio claims she became ill.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub. Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

You must be logged in to post a comment.