The nine Hale brothers of Coventry, Connecticut supported the Patriot side from the earliest days of the American Revolution. Five of them participated in the battles at Lexington and Concord. Nathan was the youngest and destined to be the most famous of them all. He was still at home at this time, finishing out the term of a teaching contract in New London, Connecticut.

Nathan Hale’s unit participated in the siege of Boston. Hale himself joined General George Washington’s army in the spring of 1776, as the army moved to Long Island to block the British move on the strategically important port city of New York.

On June 29, General Howe appeared off Staten Island with a fleet of 45 ships. By the end of the week, he’d assembled an overwhelming fleet of 130.

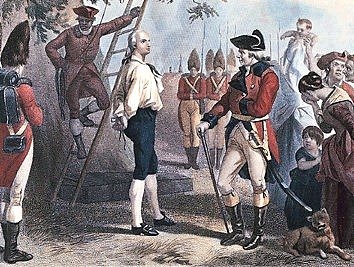

There was an attempt at peaceful negotiation on July 13, when General Howe sent a letter to General Washington under flag of truce. The letter was addressed “George Washington, Esq.”, intentionally omitting Washington’s rank. Washington declined to receive the letter, responding that there was no one present by that address. Howe tried the letter again on the 16th, this time addressing “George Washington, Esq., etc., etc.”. Again, Howe’s letter was refused.

The following day, General Howe sent Captain Nisbet Balfour in person to ask if Washington would meet with Howe’s adjutant, Colonel James Patterson. Considerations of honor having thus been settled, a meeting was scheduled for July 20.

Patterson told Washington that General Howe had come with powers to grant pardons. Washington refused, saying “Those who have committed no fault want no pardon”.

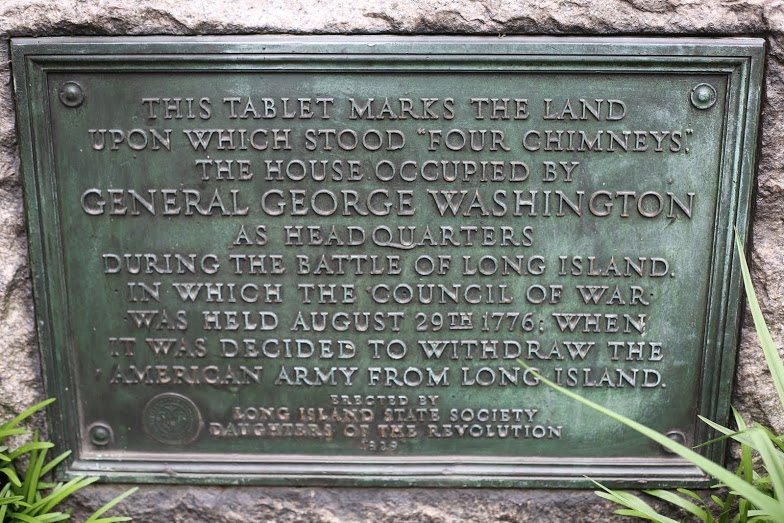

Patriot forces were comprehensively defeated at the Battle of Brooklyn, fought on August 27, 1776. With the Royal Navy in command on the water, Howe’s army dug in for a siege, confident that the adversary was trapped and waiting to be destroyed at their convenience.

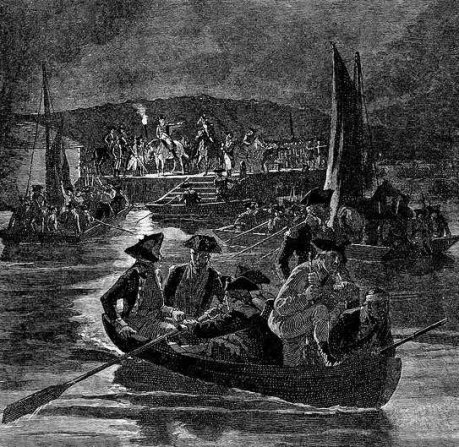

On the night of August 29-30, Washington withdrew his army to the ferry landing and across the East River, to Manhattan.

With horse’s hooves and wagon wheels muffled, oarlocks stuffed with rags, the Patriot army withdrew even as a rearguard tended fires, convincing the redcoats in their trenches that the Americans were still there.

The surprise was comprehensive for the British side, on waking on the morning of the 30th. The Patriot army had vanished.

The Battle of Long Island would almost certainly have ended in disaster for the Patriot cause but for that silent evacuation over the night of August 29-30, one of the great military feats of the American revolution.

Following evacuation, the Patriot army found itself isolated on Manhattan island, virtually surrounded. Only the thoroughly disagreeable current conditions of the Throg’s Neck-Hell’s Gate segment of the East River prevented Admiral Sir Richard Howe (William’s brother) from enveloping Washington’s position, altogether.

Expecting a British assault in September, General Washington became increasingly desperate for information on British movements.

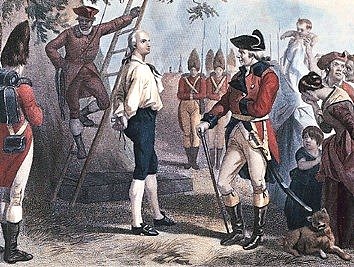

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale.

Hale set out on his mission on September 10, disguised as a Dutch schoolmaster. He was successful for about a week but appears to have been something less than “street smart”. The young and untrained Patriot turned spy, bestowed his trust where it did not belong.

Major Robert Rogers was an old British hand, a leader of Rangers during the earlier French and Indian War. Rogers must have suspected that this Connecticut schoolteacher was more than he pretended to be, intimating that he himself was a spy in the Patriot cause.

Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper was himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War. Tiffany recorded what happened next in his journal:

“The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.”

“Stay behind spy” Hercules Mulligan had better success, reporting on British goings-on from the 1776 capture of New York to their withdrawal seven years later. But that must be a story for another day.

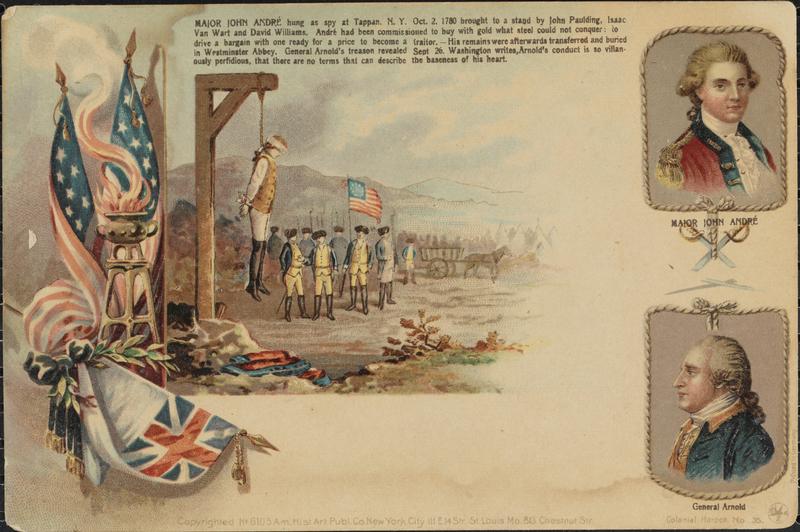

Nathan Hale was hanged on this day in 1776, described by CIA.gov as “The first American executed for spying for his country”.

There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words. However, an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor exists. He was present at the hanging.

Montresor spoke with American Captain William Hull the following day under flag of truce. The captain gave Hull the following account: “‘On the morning of his execution,’ said Montresor, ‘my station was near the fatal spot, and I requested the Provost Marshal to permit the prisoner to sit in my marquee, while he was making the necessary preparations. Captain Hale entered: he was calm, and bore himself with gentle dignity, in the consciousness of rectitude and high intentions. He asked for writing materials, which I furnished him: he wrote two letters, one to his mother and one to a brother officer.’ He was shortly after summoned to the gallows. But a few persons were around him, yet his characteristic dying words were remembered. He said, ‘I only regret, that I have but one life to lose for my country‘.

Nathan Hale was barely three months past his 21st birthday on the day he died.

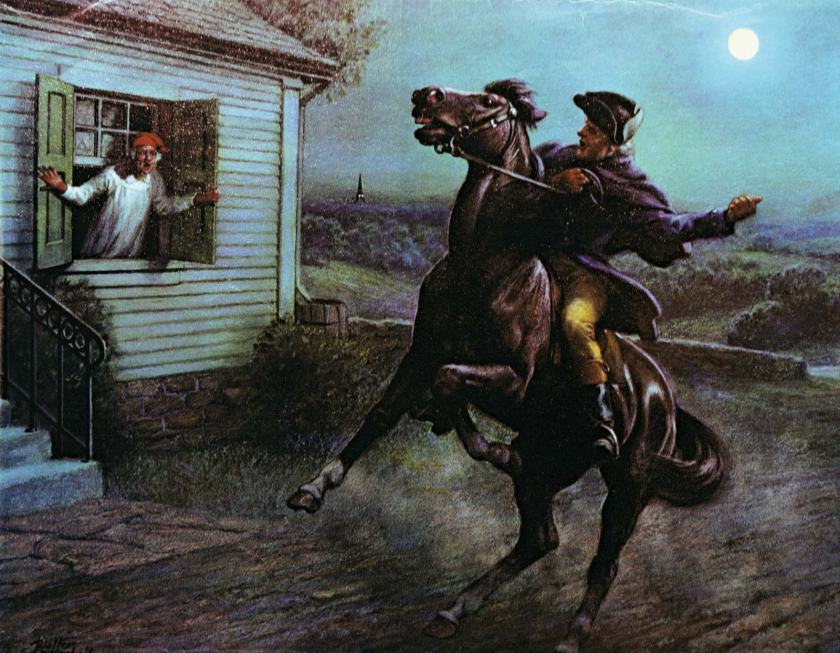

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

In 1582, France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian moving New Year to January 1 as specified by the Council of Trent, of 1563. Those who didn’t get the news and continued to celebrate New Year in late March/April 1, quickly became the butt of jokes and hoaxes.

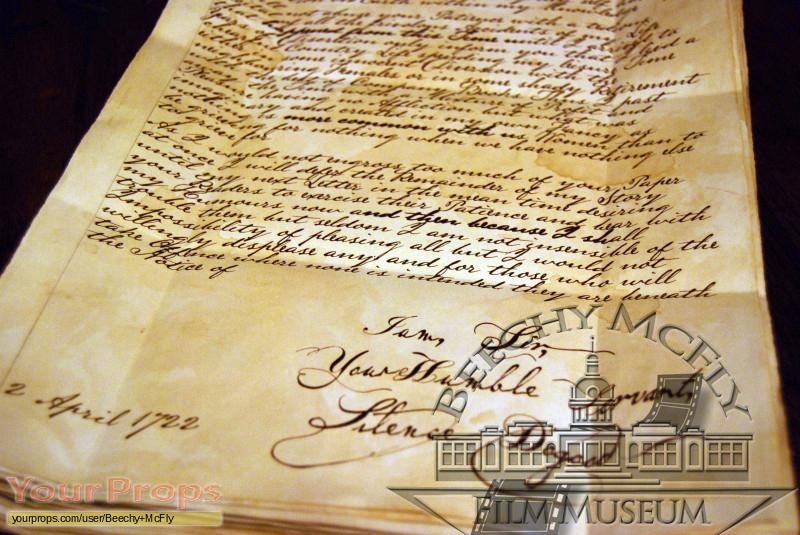

In 1582, France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian moving New Year to January 1 as specified by the Council of Trent, of 1563. Those who didn’t get the news and continued to celebrate New Year in late March/April 1, quickly became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. In Scotland, April Fools’ Day is traditionally called Hunt-the-Gowk Day. Though the term has fallen into disuse, a “gowk” is a cuckoo or a foolish person. The prank consists of asking someone to deliver a sealed message requesting unspecified assistance. The message reads “Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile”. On reading the message, the recipient will explain that in order to help, he’ll first need to contact another person, sending the victim on down the road with the same message.

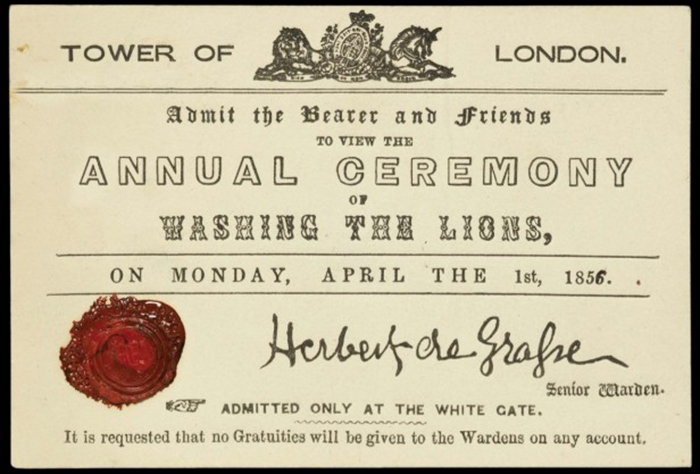

In Scotland, April Fools’ Day is traditionally called Hunt-the-Gowk Day. Though the term has fallen into disuse, a “gowk” is a cuckoo or a foolish person. The prank consists of asking someone to deliver a sealed message requesting unspecified assistance. The message reads “Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile”. On reading the message, the recipient will explain that in order to help, he’ll first need to contact another person, sending the victim on down the road with the same message. Animals were kept at the Tower of London since the 13th century, when Emperor Frederic II sent three leopards to King Henry III. In later years, elephants, lions and even a polar bear were added to the collection, the polar bear trained to catch fish in the Thames.

Animals were kept at the Tower of London since the 13th century, when Emperor Frederic II sent three leopards to King Henry III. In later years, elephants, lions and even a polar bear were added to the collection, the polar bear trained to catch fish in the Thames. In “Reminiscences of an Old Bohemian”, Gustave Strauss laments his complicity in the hoax in 1848. “These wretched conspirators”, as Straus called his accomplices, “had a great number of order-cards printed, admitting “bearer and friends” to the White Tower, on the 1st day of April, to witness…the famous grand annual ceremony of washing the lions”.

In “Reminiscences of an Old Bohemian”, Gustave Strauss laments his complicity in the hoax in 1848. “These wretched conspirators”, as Straus called his accomplices, “had a great number of order-cards printed, admitting “bearer and friends” to the White Tower, on the 1st day of April, to witness…the famous grand annual ceremony of washing the lions”. In 1957, (you can guess the date), the BBC reported the delightful news that mild winter weather had virtually eradicated the dread spaghetti weevil of Switzerland. Swiss farmers were now happily anticipating a bumper crop of spaghetti. Footage showed smiling Swiss, happily picking spaghetti from the trees.

In 1957, (you can guess the date), the BBC reported the delightful news that mild winter weather had virtually eradicated the dread spaghetti weevil of Switzerland. Swiss farmers were now happily anticipating a bumper crop of spaghetti. Footage showed smiling Swiss, happily picking spaghetti from the trees.

The Warby Parker Company website describes a company mission of “offer[ing] designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses”.

The Warby Parker Company website describes a company mission of “offer[ing] designer eyewear at a revolutionary price, while leading the way for socially conscious businesses”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.