Tensions between Russia and the Scandinavian nations are nothing new, dating back to the age of the Czars when modern-day Finland was a realm of the Swedish King.

As the result of the Russo-Swedish war of 1808-09, Sweden ceded the eastern third of its territory to the Russian Empire of Czar Alexander I, to be administered as the autonomous Duchy of Finland.

Encouraged by the collapse of the Czar and the birth of the communist state, Finland declared independence in 1917. For the first time in its history, Finland was now a sovereign state.

Soviet leader Josef Stalin was wary of Nazi aggression and needed to shore up defenses around the northern city of Leningrad. In 1939, Stalin demanded a 16-mile adjustment of the Russian-Finnish border along the Karelian Isthmus, plus several islands in the Gulf of Finland, on which to build a naval base.

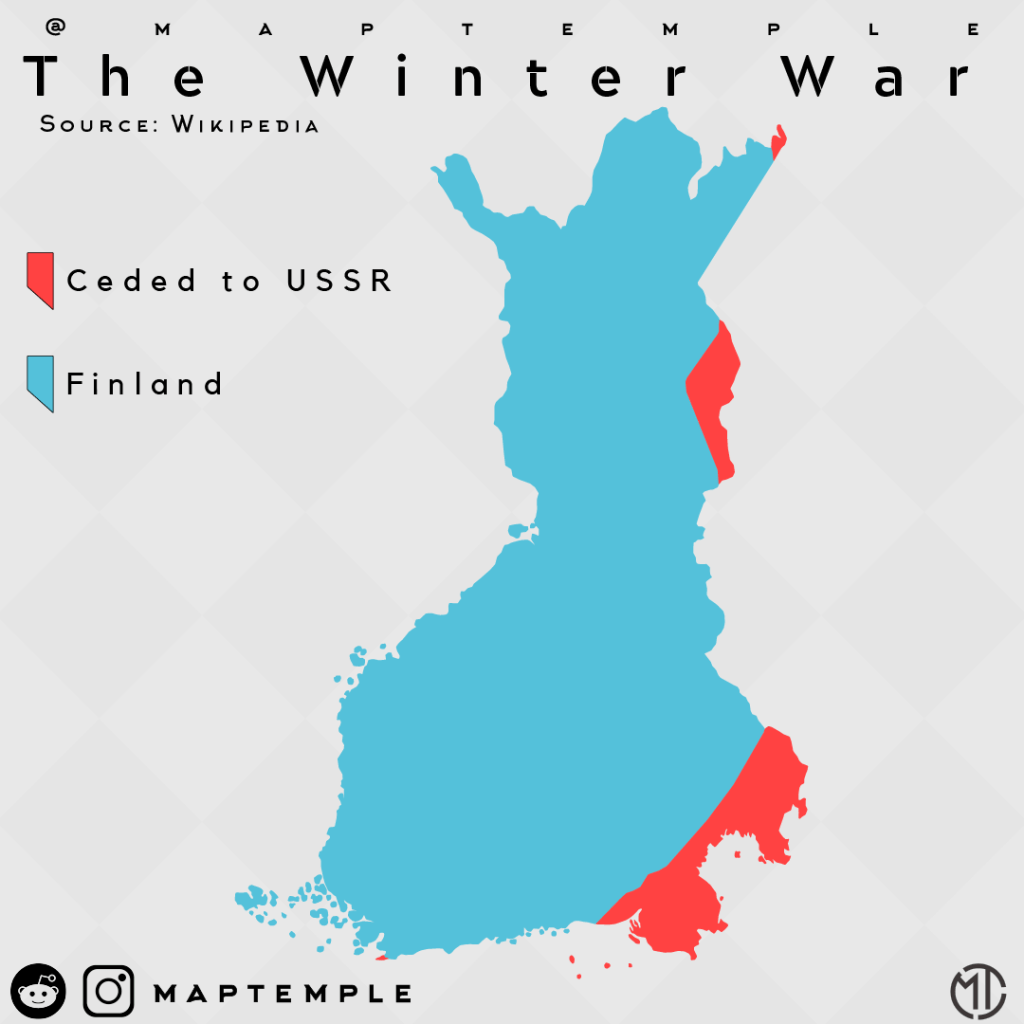

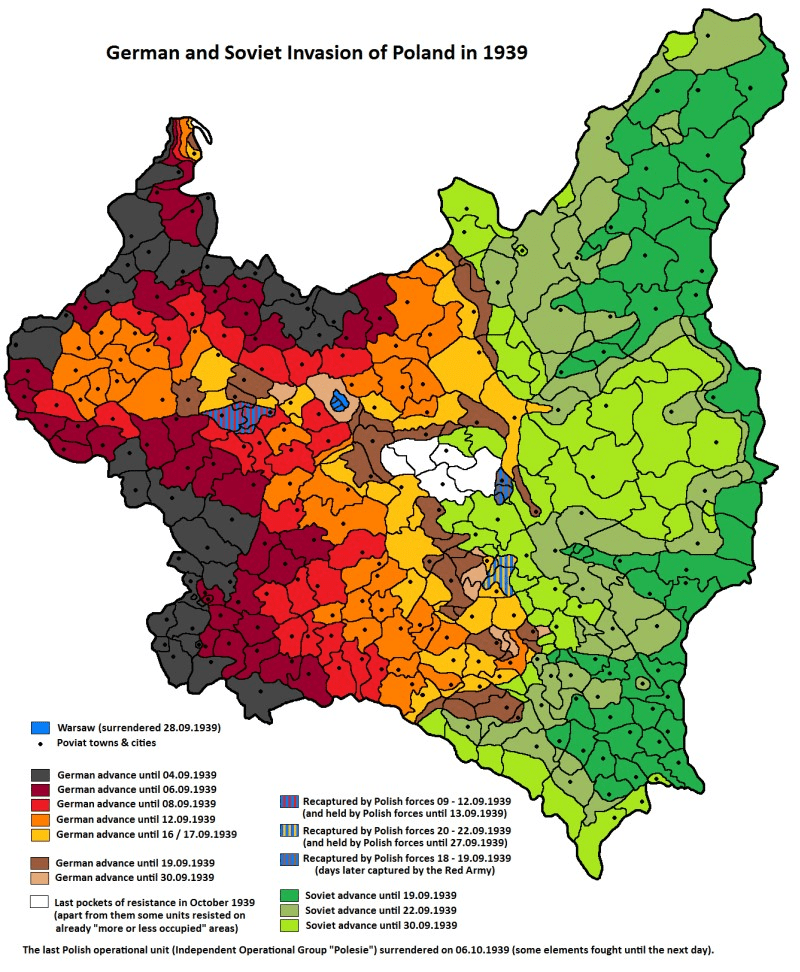

The Soviet proposal ceded fully 8% of Finnish territory. Unsurprisingly, the Finns refused. Stalin saw his opportunity with the German invasion of Poland that September. The Soviet Union attacked on November 30, 1939. The “Winter War” had begun.

Massively outnumbered, outgunned, Finnish forces nevertheless inflicted horrendous casualties on the Soviet invaders. Clad in white camouflaged gear, the Finnish sniper Simo Häyhä alone ran up an impressive 505 confirmed kills in only 100 days, after which he was shot in the face.

According to most accounts, Häyhä is the deadliest sniper in history, for which he is remembered as ‘The White Death’.

Over the night of December 10-11, Soviet forces attacked Finnish supply lines near Tolvajärvi. Famished after 5 days’ marching in the sub-zero cold, soldiers stopped to devour sausage stew left by retreating Finns.

This gave Finnish Major Aaro Pajari time to muster forces for the counterattack, including dispersed cooks and medics. The ensuing Battle of Varolampi Pond is also remembered as the “Sausage War”, one of few instances of bayonet combat from the Russo-Finnish war. 20 were killed on the Finnish side at a cost of five times that number for the Russians.

Despite such lopsided casualties, little Finland never had a chance. The Winter War ceased in March 1940 with Finland losing vast swaths of territory.

The dismal Soviet performance persuaded the German Fuhrer that the time was right for “Operation Barbarossa.” Hitler’s invasion of his Soviet “ally” began on June 22, 1941.

Three days later, Soviet air raids over Finnish cities prompted a Finnish declaration of war.

The ‘Continuation War’ was every bit the David vs. Goliath contest of the earlier Winter War. And equally savage. Soviet casualties are estimated as high as a million plus to approximately one fourth of that for the Finns.

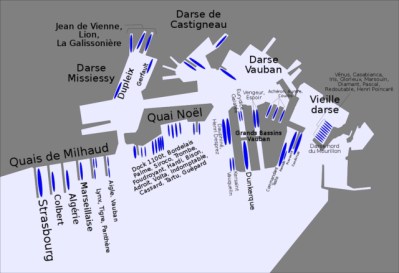

At one point, the Soviets were forced to evacuate the Karelian city of Viipuri, known today as Vyborg. On retaking the city, Finnish forces encountered hundreds of mines. Military personnel were being blown to bits by hundreds of these things, seemingly set to explode at random.

One such bomb was discovered intact under the Moonlight Bridge. Some 600kg of explosives with an unusual timer. Jouko Pohjanpalo examined the device, an electronics wiz kid known as the “father of Finnish radio”, Pohjanpalo discovered this was no timer at all. This was a radio receiver with three tuning forks, set to oscillate at frequencies unique to each mine.

The devices were detonated by sound, transmitted by radio. One three-note chord was all that was needed… and… Boom.

A countermeasure was required. Musical notes played hard and fast, overriding those three tones.

Accordion music.

A truck was rigged to transmit a popular dance tune of the era, an REO 2L 4 210 Speedwagon, broadcasting the Säkkijärvi polka.

Russians switched to a second radio frequency and then a third. In the end, three broadcast vehicles crisscrossed the streets of Viipuri plus, additional 50-watt stationery transmitters.

Broadcast in three frequencies the polka played on in endless loop from September 9, 1941 until February 2, 1942. The effect was electric. Patriotic. Dance music as military counter-measure, played in two-quarter time. If you’re an American reading this, picture Lee Greenwood’s song. I’m proud to be an American. On repeat. Hell yeah. You got the idea.

Protected by that sonic umbrella, bomb disposal techs raced to deactivate the devices. Some 1,200 bombs were discovered. Over three months, only 20 exploded. By then it didn’t matter. The rest of the batteries were dead.

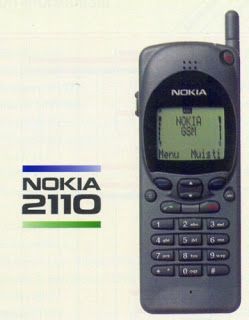

Fifty years later, the Finnish telecommunications company Nokia introduced the 2110, the first cell phone with selectable ringtones. Among the choices programmed into the phone – The Säkkijärvi Polka.

You must be logged in to post a comment.