December 5, 1941 was a Friday. The conflict destined to be known as World War 2 was still, “over there”. The United States was neutral, and at peace. The aircraft carrier USS Lexington and five heavy cruisers leave the US Pacific naval anchorage at Pearl Harbor, unaware that only yesterday, Emperor Hirohito approved the attack to be carried out in two days.

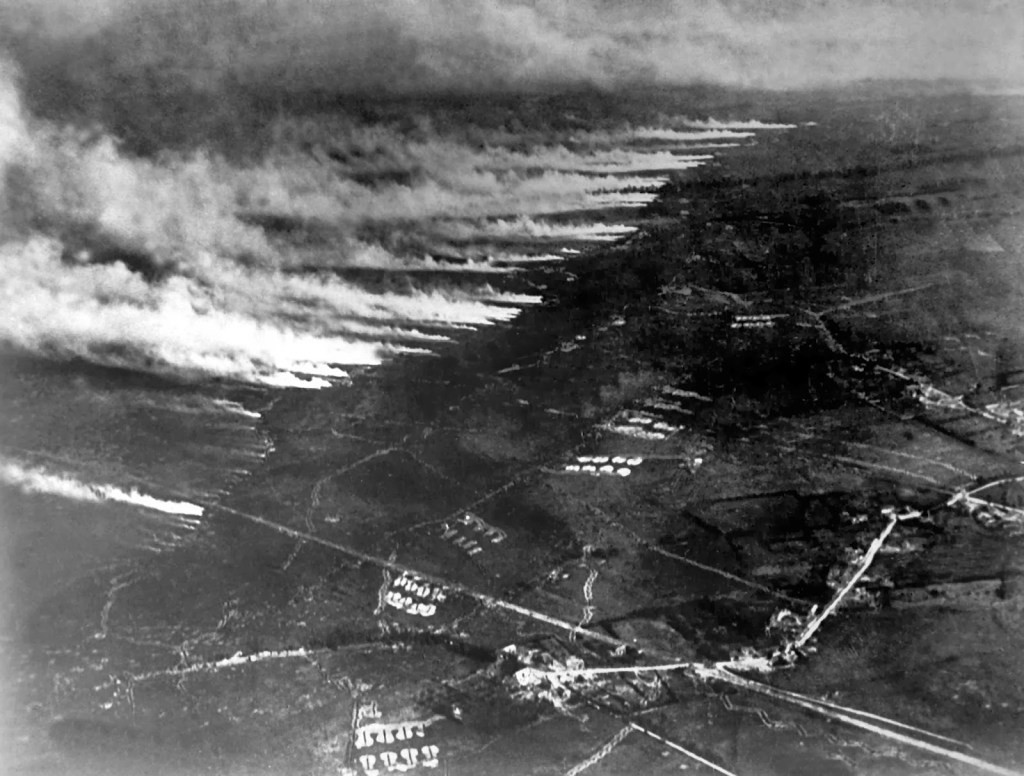

It was literally “out of the blue”, when that first wave of enemy aircraft arrived at 7:48 local time, December 7, 1941. 353 Imperial Japanese warplanes approached in two waves out of the southeast, fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes, across Hickam Air Field and over the waters of Pearl Harbor. Tied in place and immobile, the eight vessels moored at “Battleship Row” were easy targets.

In the center of the Japanese flight path, sailors and Marines aboard USS Oklahoma fought back furiously. She didn’t have a chance. Holes as wide as 40-feet were torn into the hull in the first ten minutes. Eight torpedoes crashed into her port side, each striking higher up as the Battleship slowly rolled over.

Bilge inspection plates were removed for a scheduled inspection that Monday making counter-flooding to prevent capsize, impossible. Oklahoma rolled over and died as the ninth torpedo slammed home. Hundreds scrambled out across the rolling hull, jumping overboard into the oil covered, flaming waters of the harbor, or crawling out onto mooring lines in the attempt to reach USS Maryland in the next berth.Nine Japanese torpedoes struck Oklahoma’s port side, in the first ten minutes.

The damage was catastrophic. Once the pride of the Pacific fleet, all eight battleships were damaged, four sunk. Nine cruisers, destroyers and other ships were damaged and another two sunk. 347 aircraft were damaged, most while still on the ground. 159 of those were destroyed altogether. 2,403 were dead or destined to die from the attack, another 1,178 wounded.

Frantic around the clock rescue efforts began almost immediately, to get at 461 sailors and Marines trapped within the hull of the Oklahoma. Tapping could be heard as holes were drilled to get to those trapped inside. 32 of them were delivered from certain death.

14 Marines and 415 sailors lost their lives on board Oklahoma, either immediately, or in the days and weeks to come. Bulkhead markings would later reveal that, at least some of the doomed would live for another seventeen days in the black, upside-down hull of that ship. The last such mark was drawn by the last survivor on Christmas Eve.

It is a searing act of imagination, merely to contemplate those 17 days. Trapped and disoriented inside that black, upside down hell, waiting and desperately hoping for a rescue that would come, too late.

A searing act, merely of the imagination. What would it be the to enter such a place, as an act of free will?

Let’s rewind. To 1914.

Early attempts had failed to build a sea-level canal across the 50-mile isthmus of Panama. It was decided instead, the canal would be comprised of a system of locks. The giant crane barges Ajax and Hercules were ordered in 1913, to handle the locks and other large parts,for building the canal. The two cranes arrived in Cristóbal, Colón, Panama on December 7, 1914.

Much of the world was at war at this time while the United States, remained neutral.

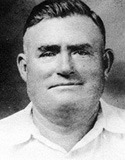

Henry Breault was born to be a sailor. At sixteen he enlisted in the British Royal Navy. For four years, the Connecticut-born Vermonter served under the White Ensign. When his four-year tour ended in 1921, he joined the US Navy.

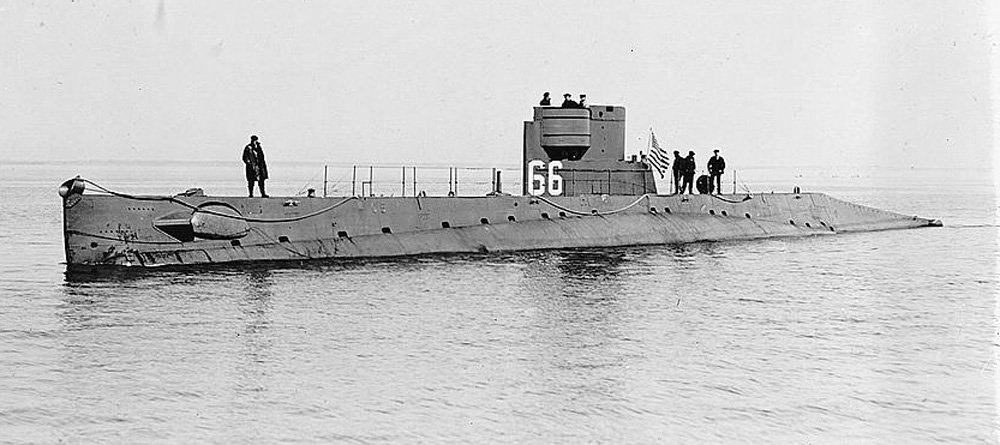

In 1923, now-torpedoman First Class Henry Breault was assigned to the O-Class submarine USS O-5 (SS-66). On October 28, O-5 under the command of Lieutenant Harrison Avery was leading a column of submarines across Limon Bay, toward the canal entrance.

The steamship SS Abangarez, owned by the United Fruit Company, was underway and headed for dock 6, at Cristobal. There were navigational errors and miscommunications and, at about 0630, Abangarez collided with the submarine, tearing a ten-foot opening on her starboard side.USS O-5

The main ballast tank was breached. O-5 was doomed. As the submarine rolled sharply to port and then to starboard, Avery gave the order to abandon ship. Breault was a few short steps to safety when he realized. Chief Electrician’s Mate Lawrence T. Brown was still below, sleeping. As the bow was going under, Breault shut the deck hatch over his head, and went below.

Brown was awake by this time, but unaware of the order to abandon ship. The pair headed aft toward the control hatch, but it was too late. With the dying sub rapidly filling with water, Breault and Brown made their way to the torpedo room, and dogged the main hatch. Seconds later the battery shorted, and exploded. The two men were trapped under 42-feet of water with no food, no water and only a single flashlight, to pierce the stale air of that tiny, pitch black compartment. It was all over in about a minute.

Salvage efforts were underway almost immediately, from nearby submarine base Coco Solo. By 10:00, divers were on the bottom, examining the wreck. Divers hammered on the hull starting aft and working forward, in a search for survivors. On reaching the torpedo room they were answered, by the taps of a hammer.

Someone’s still alive in that thing.

There were no means of rescue in those days, save for physically lifting the submarine with pontoons, or crane. There were no pontoons within 2,000 miles but the giant crane barges Ajax and Hercules were in the canal zone, working to clear a landslide from Gaillard Cut. (Now known as the Culebra cut).“The Culebra Cut. An artificial valley along the Pacific Ocean to Gatun Lake (ahead) and eventually the Caribbean Sea.

A simple excavation now became a frantic effort to clear enough debris for Ajax, to squeeze herself through the cut.

Divers worked around the clock to dig a tunnel under the sub, through which to snake a cable. Sheppard J. Shreaves, supervisor of the Panama Canal’s salvage crew and himself a qualified diver, explained: “The O-5 lay upright in several feet of soft, oozing mud, and I began water jetting a trench under the bow. Sluicing through the ooze was easy; too easy, for it could cave in and bury me. … Swirling black mud engulfed me, I worked solely by feel and instinct. I had to be careful that I didn’t dredge too much from under the bow for fear the O-5 would crush down on me.”

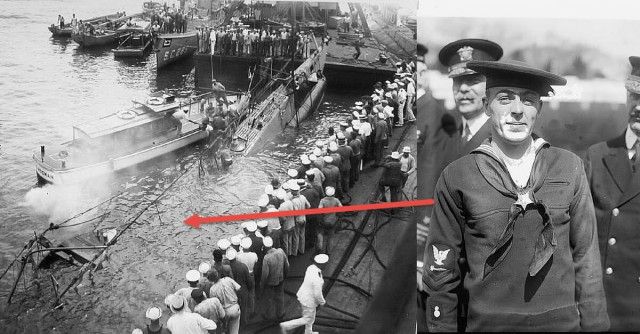

Ajax arrived around midnight and by early morning the tunnel had been dug, the cables run and attached to Ajax’ hook. Cables strained as the lift began and then…disaster. The cable snapped.

Inside, the headaches were terrific from the pressure and the stale air but all around them, they could hear it. The scraping sounds could only mean one thing. Rescue was on the way.

Sheppard Shreaves and his team of exhausted divers were now in their suits for nearly 24 hours, working to snake a second set of cables under the bow. Again the strain, as Ajax brought up the slack. Again…disaster. The second set of cables snapped.

Midnight was approaching on the 29th when the third attempt began, this time with buoyancy added, by blowing air into the flooded engine room. O-5 broke the surface just after midnight. For the first time in 31 hours, two men were able to breathe fresh air. The pair were rushed to the base at Coco Solo for medical examination, and to decompress.

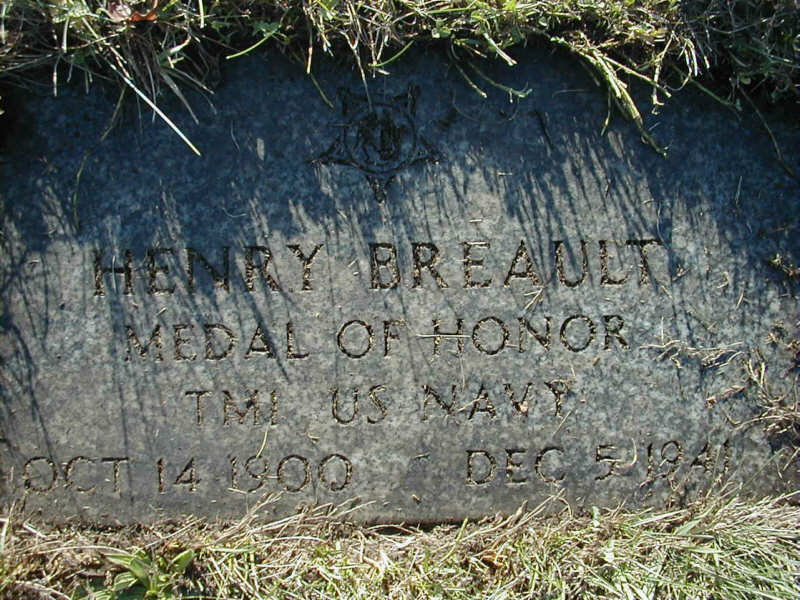

Henry Breault received the Medal of honor for what he did that day. Sheppard Shreaves received the Congressional Life Saving Medal, personally presented by Henry Breault and Lawrence Brown along with a gold engraved watch, a gift from the grateful submariners of Coco Solo.

Henry Breault served 20 years with the US Navy and later became ill, with a heart condition. He passed away on December 5, 1941 at the age of 41, and went to his rest in St. Mary’s cemetery, in Putnam Connecticut. To this day the man remains the only enlisted submariner in history, to receive the Medal of Honor.

You must be logged in to post a comment.