The German submarine U-202 commanded by Hans Linder came to the surface on the night of June 12 at Amagansett, New York, near Montauk Point. An inflatable emerged from the hatch and rowed to shore at what is now Atlantic Ave beach, in Long Island. Four figures stepped onto the beach wearing German military uniforms. If they’d been captured at this point every one of them wanted to be treated as enemy combatants, instead of spies.

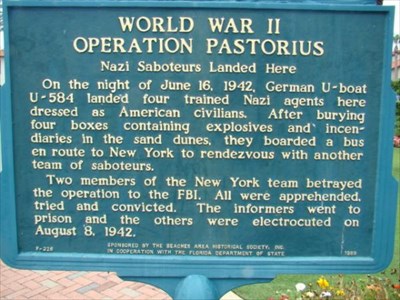

This was “Operation Pastorius”, a mission was to sabotage American economic targets and damage defense production. Targets included hydroelectric plants, train bridges and factories. The four had nearly $175,000 in cash, some good liquor and enough explosives to last them two years or more.

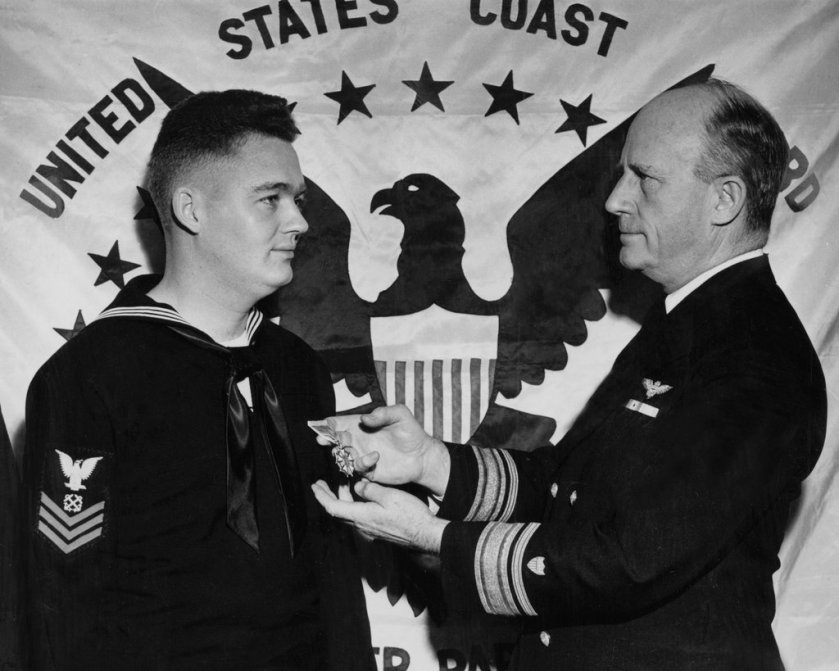

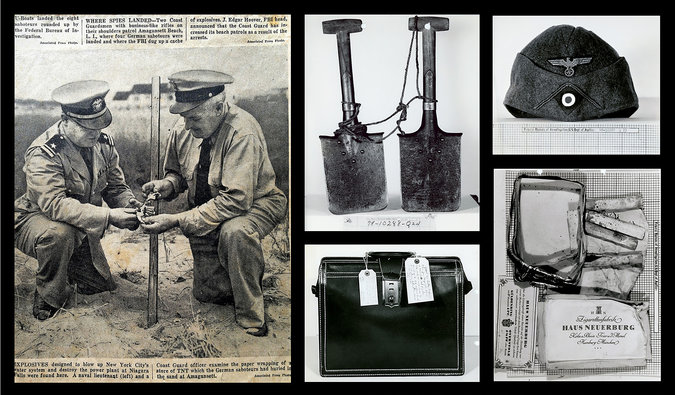

German plans began to unravel as they buried their uniforms and explosives in the sand. 21-year old Coast Guardsman John Cullen was a “sand pounder”. Armed only with a flashlight and a flare gun, Cullen had the unglamorous duty of patrolling the beaches, looking for suspicious activity.

It was “so foggy that I couldn’t see my shoes” Cullen said, when a solitary figure came out of the dunes. He was George John Davis he said, a fisherman run ashore. But something seemed wrong and Cullen’s suspicions were heightened, when another figure came out of the darkness. This one was shouting something in German, when “Davis” spun around and shouted, “You damn fool! Go back to the others!”

With standing orders to kill anyone who confronted them during the landing, Davis hissed, “Do you have a mother? A father? Well, I wouldn’t want to have to kill you.”

It was Cullen’s lucky day. “Davis’” real name was Georg John Dasch. He was no Nazi. He’d been a waiter and dishwasher before the war, who’d come to the attention of the German High Command because he had lived for a time, in the United States. “Forget about this, take this money, and go have a good time” he said, handing over a wad of bills. $260 richer, John Cullen sprinted two miles directly to the Coast guard station.

Before long the beach was swarming with Coast Guardsmen. A dawn broke it was easy to see something heavy had been dragged, across the sand. Within minutes boxes were found containing Nazi uniforms.

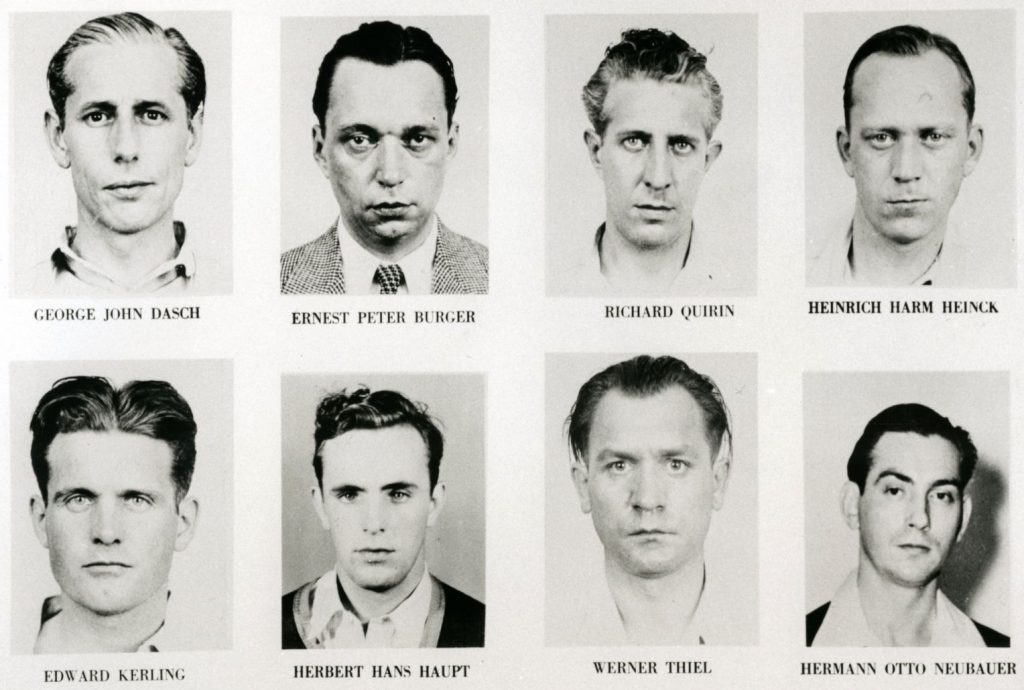

Four days later, U-584 deposited a second team of four at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, south of Jacksonville. As with the first, this second group had lived and worked in the United States, and were fluent in English. Two of the eight were US citizens.

Georg Dasch had a secret. He had no intention of carrying out his mission. He summoned Ernst Peter Burger to an upper-level hotel room. Gesturing toward an open window Dasch said “You and I are going to have a talk, and if we disagree, only one of us will walk out that door—the other will fly out this window.”

Burger turned out to be a naturalized US citizen who’d spent 17 months in a concentration camp. He hated the Nazis as much as Dasch. Then and there, the two of them decided to defect.

Dasch tested the waters. Convinced the FBI was infiltrated with Nazi agents, he telephoned the New York field office. Put on hold with the call transferred several times, Dasch was horrified to have the agent who finally listened to him, quietly hang up the phone. Had he reached a German mole? Had the call been traced?

Dasch had no way of knowing, he’d been transferred to the ‘nut desk’. The FBI thought he was a clown.

Finally, Dasch went to the FBI office in Washington DC, only to be treated like a nut job. Until he dumped $84,000 cash on Assistant Director D.M. Ladd’s desk, a sum equivalent to about a million dollars, today. Dasch was interrogated for hours, and happily gave up everything he knew. Targets, German war production, he spilled it all, even a handkerchief with the names of local contacts, written in invisible ink. He couldn’t have been a very good spy, though. He forgot how to reveal the names.

All eight were in custody, within two weeks.

J. Edgar Hoover announced the German plot on June 27, but his version had little resemblance to that of Dasch and Burger. As with the brief he had given President Roosevelt, Hoover praised the magnificent work of FBI detectives and the Sherlock Holmes-like powers of deduction which led Assistant Director Ladd to that $84,000. Dasch and Burger’s role in the investigation was conveniently left out, as was the fact that the money had all but bounced Mr. Ladd off the head.

Neither Dasch nor Burger expected to be thrown in a cell, but agents assured them it was a formality. Meanwhile, a credulous and adoring media speculated on how Hoover’s FBI had done it all. Did America have spies inside the Gestapo? German High Command? Were they seriously that good?

Attorneys for the defense wanted a civilian trial, but President Roosevelt wrote to Attorney General Francis Biddle: “Surely they are as guilty as it is possible to be and it seems to me that the death penalty is almost obligatory”. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the decision “Ex parte Quirin” became and remains precedent to this day, for the way unlawful combatants are tried. All eight would appear before a military tribunal.

Whether any of the eight were the menace they were made out to be, remains unclear. German High Command had selected all eight based on past connections with the United States, and ordering them to attack what they may have regarded as their adopted country. Several were arrested in gambling establishments, others in houses of prostitution. One had resumed a relationship with an old girlfriend and the pair was planning to marry. Not the behavior patterns you might expect from “Nazi saboteurs”.

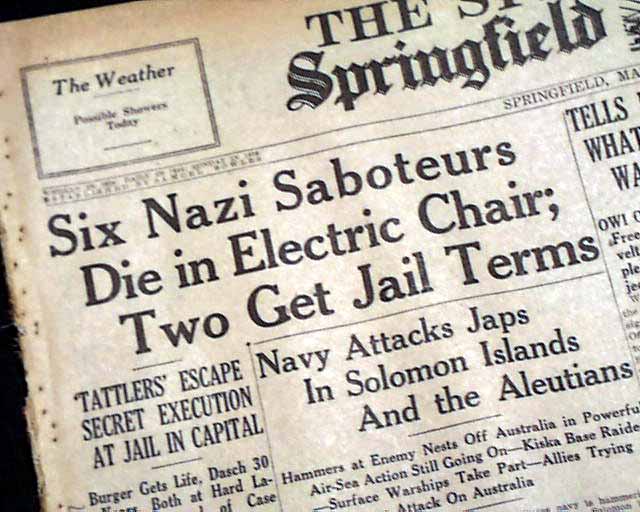

The trial was held before a closed-door military tribunal in the Department of Justice building in Washington, the first such trial since the Civil War. All eight defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death. It was only on reading trial transcripts, that Roosevelt learned the rest of the story. The President commuted Burger’s sentence to life and Dasch’s to 30 years, based on their cooperation with the prosecution. The other six were executed by electric chair on August 8, in alphabetical order.

After the war, Burger and Dasch’s trial transcripts were released to the public, over the strenuous objections of J. Edgar Hoover. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman bowed to political pressure, granting the men executive clemency and deporting them both to the American zone of occupied Germany. The pair found themselves men without a country hated as spies in America, and traitors in Germany.

The reader may decide, whether Hoover and Roosevelt operated from base and venal political motives, or whether the pair was playing 4-D chess. Be that as it may, Hitler rebuked Admiral Canaris, and seems to have bought into Hoover’s version of FBI invincibility. There would be no further missions of this type, save for one in November 1944, when two spies were landed on the coast of Maine to gather information on the Manhattan project.

Georg Dasch campaigned for the rest of his life, to be allowed to return to what he described as his adopted country. Ernst Burger died in Germany in 1975, Dasch in 1992. The pardon Hoover promised both men over a half-century earlier, never materialized.

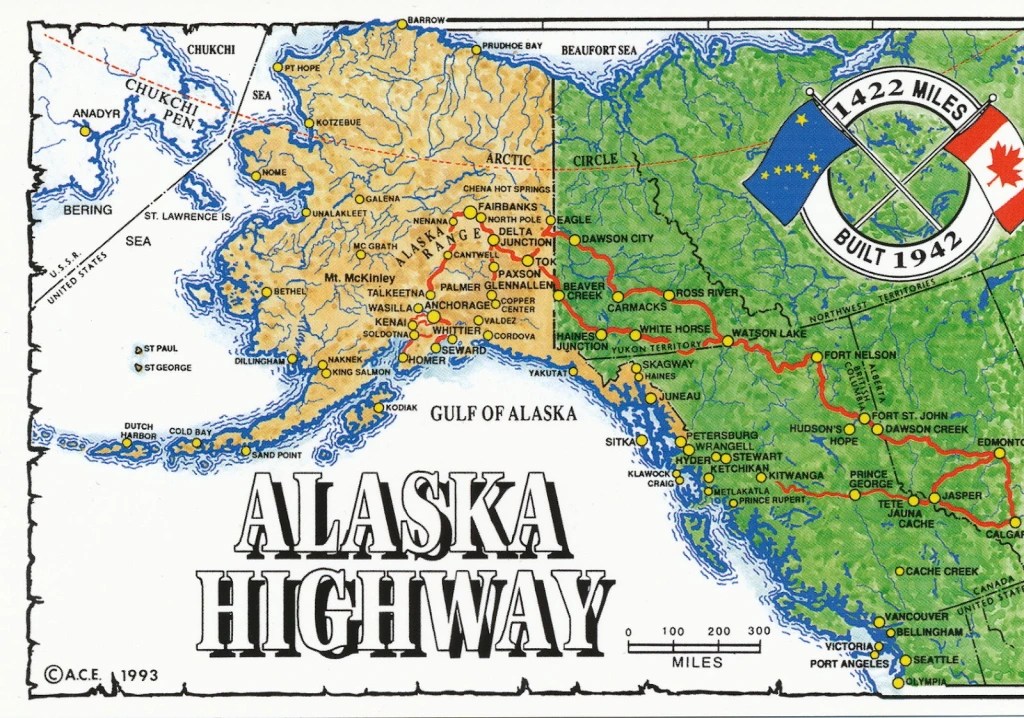

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.