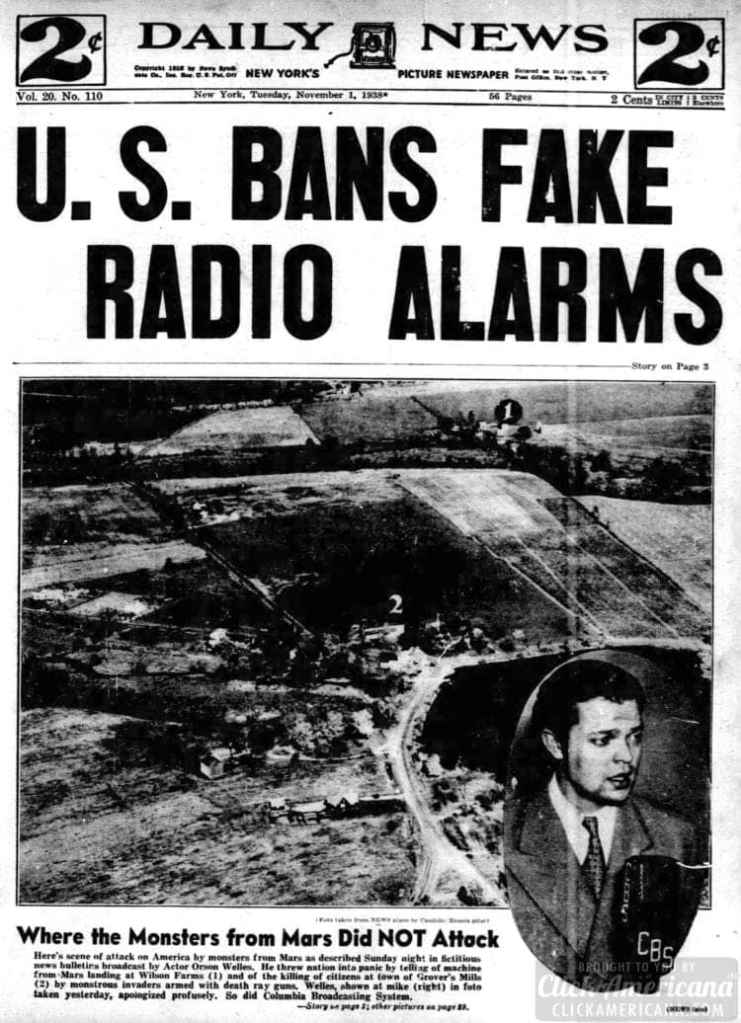

October 30, 1938 was a Sunday. The 8:00pm (eastern) broadcast of the Mercury Theater of the Air began with a weather report and then went to a dance band remote featuring “Ramon Raquello and his orchestra”. The music was periodically interrupted by live “news” flashes, beginning with strange explosions on Mars. Producer Orson Welles made his debut as the “famous” (but non-existent) Princeton Professor Dr. Richard Pierson, who dismissed speculation about life on Mars.

A short time later, another “news flash” reported a fiery crash in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. What was believed a meteorite turned out to be a rocket capsule as a tentacled, pulsating Martian unscrewed the hatch and incinerated the gathering crowd of onlookers, with a death ray.

The story is great fun, a Halloween classic telling and retelling the story of a radio broadcast leading untold thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands to take up their families and their shotguns and flee into the night, to escape the Martian menace.

1 million Americans or more according to some news outlets, members of a generation who survived the Great Depression and went on to win World War II, actually believed Martian killing machines had blasted off and traveled across interplanetary space and attacked New Jersey, only to be destroyed themselves by microorganisms, all in the space of a sixty minute broadcast.

Umm…OK.

To be fair I wrote as much myself in this space, four years ago. Then as now the healthy skeptic might have begun, by following the money.

In 1899, the obscure Brazilian priest and inventor Father Roberto Landell de Moura successfully transmitted audio over a distance, of 7 kilometers (4.3 miles). That same year an Italian inventor called Guglielmo Marconi successfully broadcast, across the English Channel. Twenty years later, Westinghouse engineer Frank Conrad began to broadcast music, in the Pittsburg, Pennsylvania area. Conrad’s broadcasts stimulated demand for crystal sets. A year later, Westinghouse started the radio station, KDKA. Within two years, KDKA was broadcasting prize fights and Major League Baseball games. By early 1927 there were 737 stations nationwide, and growing.

In the 19th century, newspapers alone carried the journalistic heft, to go toe-to-toe with the corruption of Tammany Hall and other such political machines. Books could be written about the newspaper wars of the turn-of-the-century and the Yellow Journalism which helped goad the nation, to war. A week after the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898 William Randolph Hearst’s American Journal ran the headline “How do you like the Journal’s war?”

The “stunt journalism” of Nellie Bly and her Ten Days in a Madhouse opened the door to an era of Muckraking, journalists reporting on waste, fraud and abuse in public and private life, alike.

In depression-era America, radio was not only the cheapest form of entertainment but a source for high quality programming. By the late 1930’s radio was not only the center of household entertainment but also, a center for news and information.

It was the Golden Age of radio. By 1934 some 60 percent of American households had radio sets as did 1½ million, of the nation’s automobiles. Many theaters didn’t bother to open their doors during the Amos & Andy program and those who did shut off the projectors while the show was on and hauled out, a radio.

To the news reader of the Great War period the newspaper was equal to the entire print and electronic media of our time, in all its forms.

Such was the media landscape in the inter-war years. A new and novel form of news and entertainment gaining ground almost daily, at the expense of a centuries-old competitor. Small wonder it is then that such an industry would find threat in this upstart, called radio.

And then came October 30, 1938. The War of the Worlds.

With memories of the Great War still painfully fresh and the Nazi threat looming in Europe an excitable few did indeed, take to the streets. Most had heard the repeated warnings that this was only entertainment though, or figured it out for themselves. Others did what rational people would do and picked up the phone, in search of information.

Friends and family called each other to see if they had heard anything. New York phone switchboards experienced a geometric increase in traffic, that night. New Jersey phone traffic jumped 39 percent during the broadcast. The New York Times received 875 calls about the program. The Newark Evening News logged over a thousand. Some called CBS, to congratulate them for the show. Others complained that the program was too realistic.

Then as now Sunday night newsrooms, are all but cold and dark. With few reporters working that night and little original reporting many papers relied on the Monday morning recap from organizations, like AP. And who was this irresponsible upstart in any case when the public already had a far more trusted source, for news and information?

The Associated Press reported Monday morning, a man in Pittsburgh returned home to find his wife with a bottle of poison saying “I’d rather die this way“. A woman in Indianapolis ran into a church screaming “New York is destroyed… It’s the end of the world!“. The Washington Post reported the story of one Baltimore man who died of a heart attack but somehow didn’t bother to follow up, for any of the details. The New York Times piled on with the October 31 headline “Radio listeners in panic, Taking Radio drama as fact”. The Times went on to inform its readers, “In Newark, in a single block at Heddon Terrace and Hawthorne Avenue, more than 20 families rushed out of their houses with wet handkerchiefs and towels over their faces to flee from what they believed was to be a gas raid. Some began moving household furniture”.

Long on anecdote and egregiously short on details, the print media went with the narrative blaming the entire radio industry. It was the first clue, that something wasn’t right.

“For at least a couple hours or more and really into the next morning, we believed we were mass murderers, because the press which was very hostile to radio was delighted for this opportunity to piss on radio and say they were irresponsible, and so on”.

War of the Worlds producer, John Housman

Not a single one of multiple purported deaths was ever tied directly to the War of the Worlds and yet, 83 years later the panic narrative remains, alive and well. For the 75th anniversary in 2013 USA Today reported, that “The broadcast … disrupted households, interrupted religious services, created traffic jams and clogged communications systems.”

NPR’s Morning Edition reported as recently as 2005, that “”listeners panicked, thinking the story was real. Many jumped in their cars according to the broadcast, to flee from the “invasion.” ‘Radiolab’, a program produced by New York Public Radio from 2002 to the present day reported that some 12 million people listened to that original broadcast, in 1938. 1 in 12 according to Radiolab believed the story, to be true.

The Truly Terrified likely numbered in the tens of dozens and not the tens of thousands but the narrative was already being set. What better tools to apply but fear and mockery, techniques we see in common use, to this day.

The War of the Worlds broadcast was, in the end, what it described itself to be. A Halloween concoction. The equivalent of dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, ‘Boo!’. Instead, the story remains one of our great and enduring media hoaxes giving proof where little is required, of Winston Churchill’s wise and timeless advice: “A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on“.

You must be logged in to post a comment.