There’s an old cliché that, if you speak with those who are convicted of a crime, all of them will say they are innocent. It’s an untrue statement on its face, but only two possible conclusions are possible, in the alternative. Either all convicts are guilty as charged, or someone, at some time, has been wrongly convicted.

To agree with the former is to accept the premise that what government does is 100% right, 100% of the time.

Iva Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She attended schools in Calexico and San Diego, returning to Los Angeles where she enrolled at UCLA, graduating in January, 1940 with a degree in zoology.

Iva Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She attended schools in Calexico and San Diego, returning to Los Angeles where she enrolled at UCLA, graduating in January, 1940 with a degree in zoology.

In July of the following year, Iva sailed to Japan without an American passport. She variously described the purpose of the trip as the study of medicine, and going to see a sick aunt.

In September, Toguri appeared before the US Vice Consul in Japan to obtain a passport, explaining that she wished to return to permanent residence in the United States. Because she had left without a passport, her application was forwarded to the State Department for consideration. It was still on someone’s desk when Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, fewer than three months later.

Iva later withdrew the application, saying that she’d remain in Japan voluntarily for the duration of the war. She enrolled in a Japanese language and culture school to improve her language skills, taking a typist job for the Domei News Agency. In August 1943, she began a second job as a typist for Radio Tokyo.

In November of that year, Toguri was asked to become a broadcaster for Radio Tokyo on the “Zero Hour” program, part of a Japanese psychological warfare campaign designed to lower the morale of US Armed Forces. The name “Tokyo Rose” was in common use by this time, applied to as many as 12 different women broadcasting Japanese propaganda in English.

Toguri DJ’d a program with American music punctuated by Japanese slanted news articles for 1¼ hours, six days a week, starting at 6:00pm Tokyo time. Altogether, her on-air speaking time averaged 15-20 minutes for most broadcasts.

She called herself “Orphan Annie,” earning 150 yen per month (about $7.00 US). She wasn’t a professional radio personality, but many of those who recalled hearing her enjoyed the program, especially the music.

She called herself “Orphan Annie,” earning 150 yen per month (about $7.00 US). She wasn’t a professional radio personality, but many of those who recalled hearing her enjoyed the program, especially the music.

Shortly before the end of the war, Toguri married Felipe d’Aquino, a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese ancestry. The marriage was registered with the Portuguese Consulate, though she didn’t renounce her US citizenship, continuing her Zero Hour broadcast until after the war was over.

After the war, a number of reporters were looking for the mythical “Tokyo Rose”. Two of them found Iva d’Aquino.

Henry Brundidge, reporting for Cosmopolitan magazine and Clark Lee, reporter for the International News Service, must have thought they found themselves a real “dragon lady”. The pair hid d’Aquino and her husband away in the Imperial Hotel, offering $2,000 for exclusive rights to her story.

$2,000 was not an insignificant sum in 1945, equivalent to $23,000 today. Toguri lied, “confessing” that she was the “one and only” Tokyo Rose. The money never materialized, but she had signed a contract giving the two rights to her story, and identifying herself as Tokyo Rose.

FBI.gov states on its “Famous Cases” website that, “As far as its propaganda value, Army analysis suggested that the program had no negative effect on troop morale and that it might even have raised it a bit. The Army’s sole concern about the broadcasts was that “Annie” appeared to have good intelligence on U.S. ship and troop movements”.

US Army authorities arrested her in September, while the FBI and Army Counterintelligence investigated her case. By the following October, authorities decided that the evidence did not merit prosecution, and she was released.

Department of Justice likewise determined that prosecution was not warranted and matters may have ended there, except for the public outcry that accompanied d’Aquino’s return to the US. Several groups, along with the noted broadcaster Walter Winchell, were outraged that the woman they knew as “Tokyo Rose” wanted to return to this country, instead demanding her arrest on treason charges.

The US Attorney in San Francisco convened a grand jury, and d’Aquino was indicted in September, 1948. Once again quoting fbi.gov, “Problematically, Brundidge enticed a former contact of his to perjure himself in the matter”.

The trial began on July 5, 1949, lasting just short of three months. The jury found d’Aquino guilty on one of fifteen treason charges, ruling that “[O]n a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships.”

d’Aquino was sentenced to ten years and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason, only the seventh person in US history to be so convicted. She was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

d’Aquino was sentenced to ten years and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason, only the seventh person in US history to be so convicted. She was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

President Gerald Ford pardoned her on January 19, 1977, 21 years almost to the day after her release from prison. Iva Toguri d’Aquino passed away in 2006, at the age of 90. Neither perjury nor suborning charges were ever brought against Brundidge, or his witness.

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.”

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.” The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

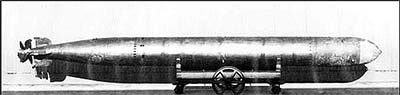

Among the Mark-XIV’s more pronounced deficiencies was a tendency to run about 10-ft. too deep, causing it to miss with depressing regularity. The magnetic exploder often caused premature firing of the warhead, and the contact exploder frequently failed altogether. There must be no worse sound to a submariner, than the metallic ‘clink’ of a dud torpedo bouncing off an enemy hull.

Among the Mark-XIV’s more pronounced deficiencies was a tendency to run about 10-ft. too deep, causing it to miss with depressing regularity. The magnetic exploder often caused premature firing of the warhead, and the contact exploder frequently failed altogether. There must be no worse sound to a submariner, than the metallic ‘clink’ of a dud torpedo bouncing off an enemy hull.

Sam Moses, writing for historynet’s “Hell and High Water,” writes, “In five war patrols between May 1944 and August 1945, the 1,500-ton Barb sank twenty-nine ships and destroyed numerous factories using shore bombardment and rockets launched from the foredeck”.

Sam Moses, writing for historynet’s “Hell and High Water,” writes, “In five war patrols between May 1944 and August 1945, the 1,500-ton Barb sank twenty-nine ships and destroyed numerous factories using shore bombardment and rockets launched from the foredeck”. Two weeks later, USS Barb spotted a 30-ship convoy, anchored in three parallel lines in Namkwan Harbor, on the China coast. Slipping past the Japanese escort guarding the harbor entrance under cover of darkness, the American submarine crept to within 3,000 yards.

Two weeks later, USS Barb spotted a 30-ship convoy, anchored in three parallel lines in Namkwan Harbor, on the China coast. Slipping past the Japanese escort guarding the harbor entrance under cover of darkness, the American submarine crept to within 3,000 yards. On completion of her 11th patrol, USS Barb underwent overhaul and alterations, including the installation of 5″ rocket launchers, setting out on her 12th and final patrol in early June.

On completion of her 11th patrol, USS Barb underwent overhaul and alterations, including the installation of 5″ rocket launchers, setting out on her 12th and final patrol in early June. Working so close to a Japanese guard tower that they could almost hear the snoring of the sentry, the eight-man team dug into the space between two ties and buried the 55-pound scuttling charge. They then dug into the space between the next two ties, and placed the battery.

Working so close to a Japanese guard tower that they could almost hear the snoring of the sentry, the eight-man team dug into the space between two ties and buried the 55-pound scuttling charge. They then dug into the space between the next two ties, and placed the battery.

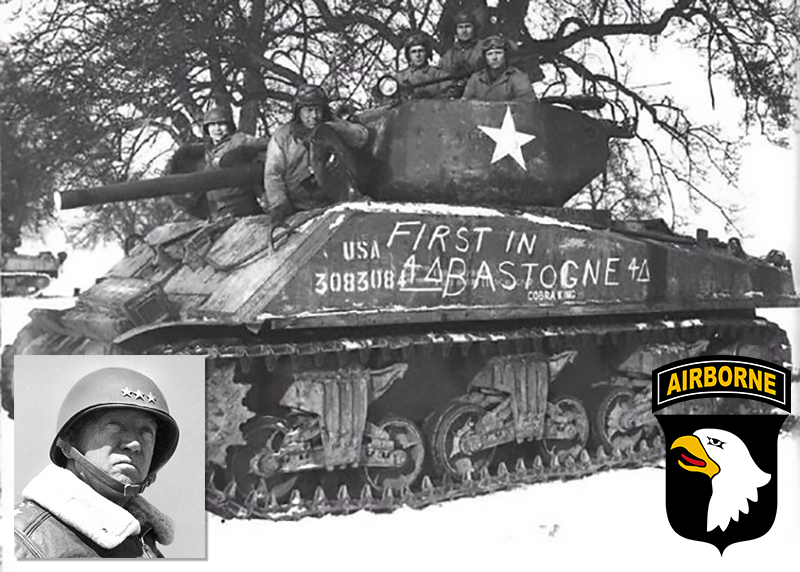

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew.

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew. Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

Necessity became the mother of invention, and the needs of war led to prodigious increases in speed. No sooner was USS Massachusetts launched, than the keel of USS Vincennes began to be laid. By the end of the war, Fore River had completed ninety-two vessels of eleven different classes.

Necessity became the mother of invention, and the needs of war led to prodigious increases in speed. No sooner was USS Massachusetts launched, than the keel of USS Vincennes began to be laid. By the end of the war, Fore River had completed ninety-two vessels of eleven different classes.

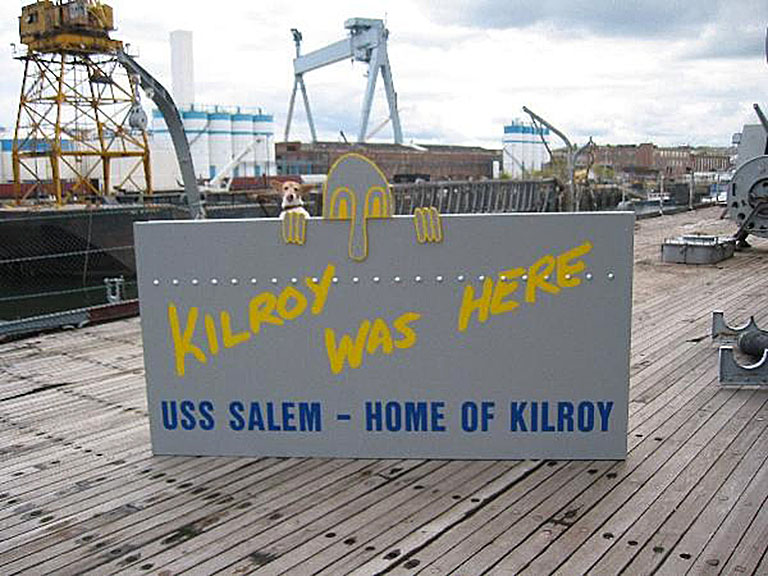

Kilroy was Here became a kind of protective talisman, and soldiers began to write it on newly captured areas and landings. He was the “Super GI”, showing up for every combat, training and occupation operation of the WW2 and Korean war era. The scribbled cartoon face was there before you arrived, and he was still there when you left.

Kilroy was Here became a kind of protective talisman, and soldiers began to write it on newly captured areas and landings. He was the “Super GI”, showing up for every combat, training and occupation operation of the WW2 and Korean war era. The scribbled cartoon face was there before you arrived, and he was still there when you left. The challenge became, who could put the Kilroy graffiti in the most difficult and surprising place. I’ve never been there, but I’ve heard that Kilroy occupies the top of Mt. Everest. His likeness is scribbled in the dust of the moon. There’s one on the Statue of Liberty, and another on the underside of the Arc of Triumph, in Paris. There are two of them engraved in the granite of the WW2 Memorial, in Washington, DC.

The challenge became, who could put the Kilroy graffiti in the most difficult and surprising place. I’ve never been there, but I’ve heard that Kilroy occupies the top of Mt. Everest. His likeness is scribbled in the dust of the moon. There’s one on the Statue of Liberty, and another on the underside of the Arc of Triumph, in Paris. There are two of them engraved in the granite of the WW2 Memorial, in Washington, DC. A Brit will tell you that “Mr. Chad” came first, cartoonist George Chatterton’s response to war rationing. “Wot, no tea”?

A Brit will tell you that “Mr. Chad” came first, cartoonist George Chatterton’s response to war rationing. “Wot, no tea”?

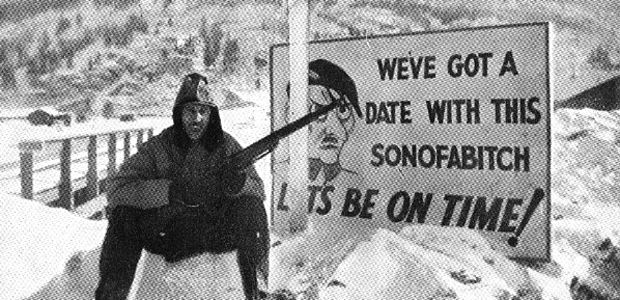

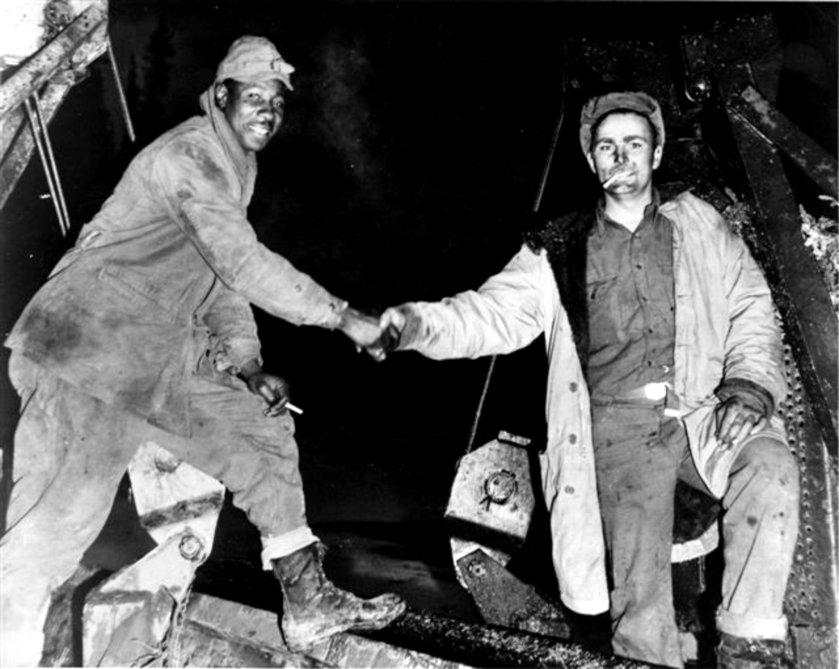

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.” The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter.

The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter. Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

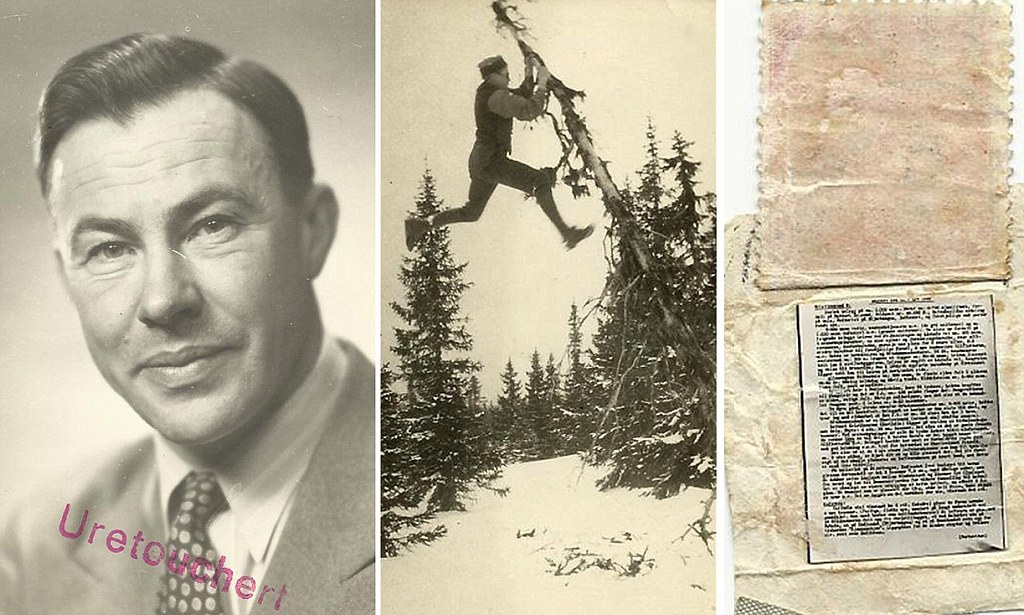

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904.

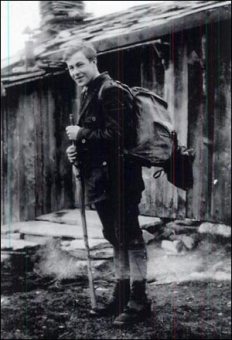

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904. The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains.

The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains. Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt. Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

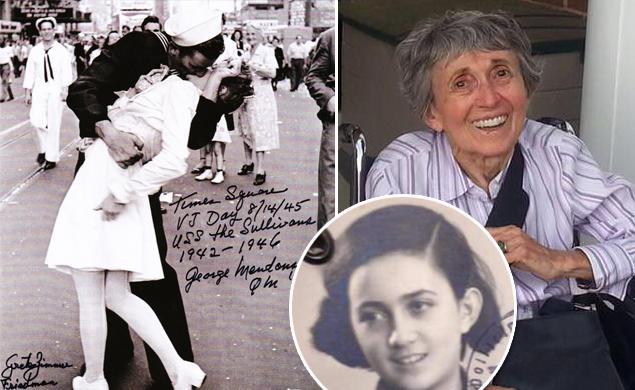

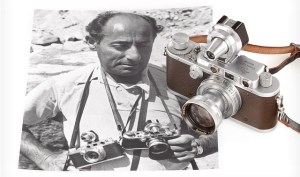

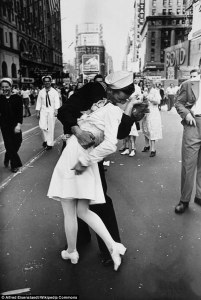

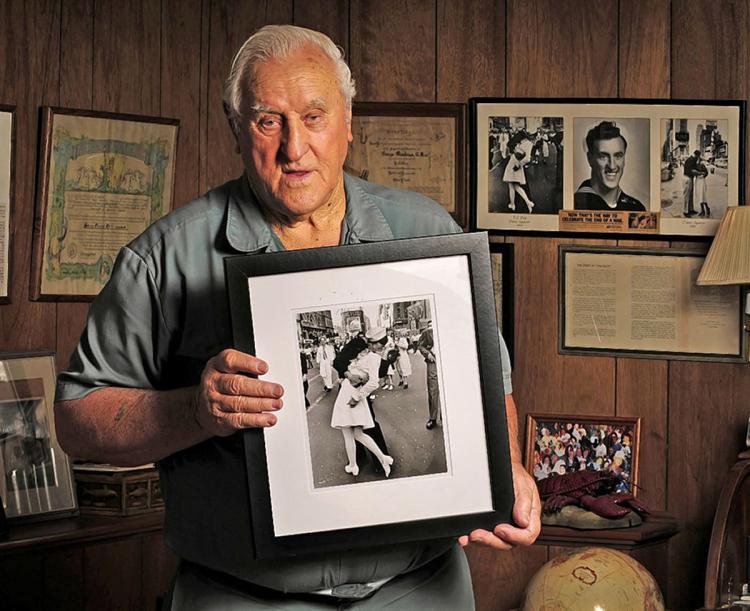

Reporters from the AP, NY Times, NY Daily News and others descended on Times Square to record the spontaneous celebration.

Reporters from the AP, NY Times, NY Daily News and others descended on Times Square to record the spontaneous celebration.

This year, the couple celebrates their 68th wedding anniversary. Rita says she wasn’t angry that her husband kissed another woman on their first date. She points out that she can been seen grinning in the background of the famous picture. She will admit, however, ‘In all these years, George has never kissed me like that.’

This year, the couple celebrates their 68th wedding anniversary. Rita says she wasn’t angry that her husband kissed another woman on their first date. She points out that she can been seen grinning in the background of the famous picture. She will admit, however, ‘In all these years, George has never kissed me like that.’

You must be logged in to post a comment.