In an age before radio or television, John André was an interesting man to be around. A gifted storyteller with a great sense of humor he could draw, paint and cut silhouettes. He was an excellent writer, he could sing, and he could write verse. John André was a British Major at the time of the American Revolution, who took part in his army’s occupations of Philadelphia and New York.

John André was a spy.

A favorite of colonial era loyalist society, Major André dated Peggy Shippen for a time, the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia loyalist. Shippen went on to marry Benedict Arnold in 1779, forming a link between the spy and an important general in the cause of American independence.

The relationship nearly changed the outcome of the American revolution.

Arnold was the Commandant of West Point at the time, the future location of one of our great military academies. A prominence overlooking the Hudson River, West Point was a fortified position offering decisive military advantage to the side holding the position. The British capture of West Point would have split the colonies in half.

The Sloop of War HMS Vulture sailed up the Hudson River on September 20, 1780, Major André meeting with General Arnold on the river’s banks the following day. Dressed in civilian clothes, John André struck a bargain with the patriot general. Arnold would receive £20,000, over a million dollars today, in exchange for which he would give up West Point.

Tasked with returning the signed papers to British lines, Major André was stopped by three Patriot Militiamen two days later. They were John Paulding, David Williams and Isaac Van Wart. One of the three wore a Hessian overcoat, making André believe they might be loyalists. “Gentlemen”, he said, “I hope you belong to our party”. “What party”, came the reply, and André said “The lower (British) party”. “We do”, they said, to which André replied that he was a British officer and must not be detained. That was as far as he got.

You need not be a military strategist to recognize the importance of the commanding heights at West Point. The discovery of those papers brought Benedict Arnold’s treachery to light. Arnold immediately fled on hearing of André’s arrest, even as George Washington was headed to his place for a meeting over breakfast.

John André was tried and sentenced to death as a spy. He asked if he could write a letter to General Washington. In it he asked not that his life be spared, but that he be executed by firing squad, a death more worthy of a gentleman than hanging, an execution at that time commonly reserved for criminals.

General Washington believed that Arnold’s crimes to be far more egregious than those of John André. Furthermore, he was impressed with the man’s courage. Washington wrote to General Sir Henry Clinton asking for an exchange of prisoners.

Having received no reply, Washington wrote in his General Order of October 2 “That Major André General to the British Army ought to be considered as a spy from the Enemy and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations it is their opinion he ought to suffer death. The Commander in Chief directs the execution of the above sentence in the usual way this afternoon at five o’clock precisely.”

John André was executed by hanging in Tappan, New York. He was 31.

John André lived for a time in Benjamin Franklin’s house back in 1777-’78, during the British occupation of Philadelphia. As he was packing to leave, Geneva-born American patriot and portrait artist Pierre-Eugène Du Simitiere came to say goodbye. The officer was always known as a gentleman. Simitiere was shocked to find André stoop to looting the home of such a prominent patriot. For a man known for extravagant courtesy, this was way out of character. André was packing books, musical instruments and scientific apparatus, even an oil portrait of Franklin, offering not so much as a response to Simitiere’s protests.

Nearly two hundred years later, the descendants of Major-General Lord Charles Grey returned the painting to the United States, explaining that André had probably looted Franklin’s home under direct orders from the General himself. A Gentleman always, it would explain the man’s inability to defend his own actions.

Today that oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs in the White House.

Benedict Arnold went on to lead British forces against his former comrades. As the story goes, Arnold once asked one of his officers what the Americans might do should he (Arnold) be captured. The officer replied: “They will cut off the leg which was wounded when you were fighting so gloriously for the cause of liberty, and bury it with the honors of war, and hang the rest of your body on a gibbet.”

The story refers to a grievous injury the turncoat general received at the Battle of Saratoga, heroically leading patriot infantry against a position remembered as Breymann redoubt. It was the second time a bullet had shattered the general’s leg in service to the Revolution. Arnold walked with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life.

On the grounds near the battlefield at Saratoga there stands the statue of a cannon’s barrel, and a leg. An officer’s boot, really, dedicated to a Hero of the Revolution. The cannon’s barrel is pointed down as a sign of dishonor. The monument declines to give this hero a name.

It is one of the most forlorn places I have ever seen.

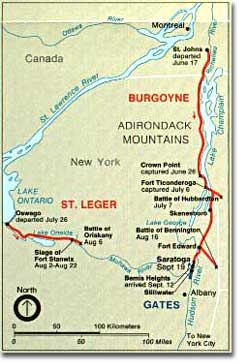

Patriot forces selected a site called Bemis Heights about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. Theirs was a formidable position with mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire.

Patriot forces selected a site called Bemis Heights about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. Theirs was a formidable position with mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777. It would have been better in the chest, he said, than to have received such a wound in that leg.

It would have been better in the chest, he said, than to have received such a wound in that leg.

“In memory of

“In memory of

You must be logged in to post a comment.