The international slave trade was illegal in most countries by 1839 while the “peculiar institution” of slavery remained legal. In April of that year, a Portuguese slave trader illegally purchased some 500 Africans and shipped them to Havana aboard the slave ship Teçora.

Conditions were so horrific aboard Teçora that fully one-third of its “cargo”, presumably healthy individuals, died on the journey. Once in Cuba, sugar cane producers Joseph Ruiz and Pedro Montez purchased 49 members of the Mende people, 49 adults and four children, for use on the plantation.

The Mendians were given Spanish names and designated “black ladinos,” fraudulently documenting the 53 to have always lived as slaves in Cuba. In June of 1841 Ruiz and Montez placed the Africans on board the schooner la Amistad, (“Friendship”), and set sail down the Cuban coast to Puerto del Principe.

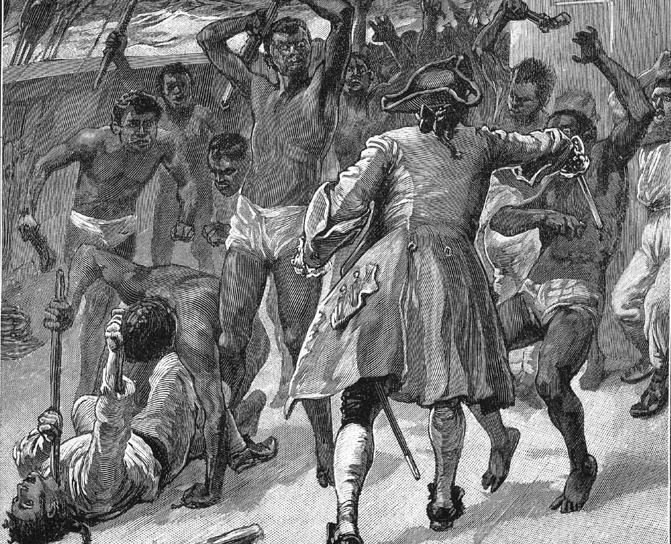

Africans had been chained onboard Teçora but chains were judged unnecessary for the short coastal trip aboard Amistad. On the second day at sea, two Mendians were whipped for an unauthorized trip to the water cask. One of them asked where they were being taken. The ship’s cook responded, they were to be killed and eaten.

The cook’s mocking response would cost him his life.

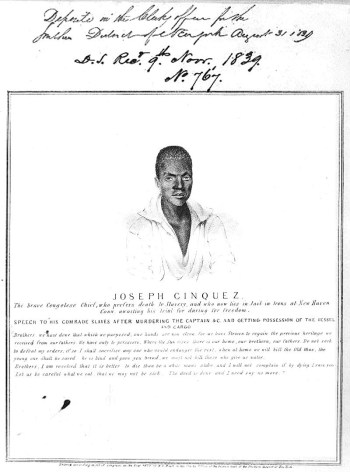

That night, captives armed with cane knives seized control of the ship. Their leader was Sengbe Pieh, also known as Joseph Cinqué. Africans killed the ship’s Captain and the cook losing two of their own in the struggle. Montez was seriously injured while Ruiz and a cabin boy named Antonio, were captured and bound. The rest of the crew escaped in a boat.

The mulatto cabin boy who really was a black ladino, would be used as translator.

Mendians forced the two to return them to their homeland, but the Africans were betrayed. By day the two would steer east, toward the African coast. By night when the position of the sun could not be determined, the pair would turn north. Toward the United States.

After 60 days at sea, Amistad came aground off Montauk on Long Island Sound. Several Africans came ashore for water when Amistad was apprehended by the US Coastal Survey brig Washington, under the command of Thomas Gedney and Richard Meade. Meanwhile on shore, Henry Green and Pelatiah Fordham (the two having nothing to do with the Washington) captured the Africans who had come ashore.

Amistad was piloted to New London Connecticut, still a slave state at that time. The Mendians were placed under the custody of United States marshals.

Both the slave trade and slavery itself were legal at this time according to Spanish law while the former was illegal in the United States. The Spanish Ambassador demanded the return of Ruiz’ and Montez’ “property”, asserting the matter should be settled under Spanish law. American President Martin van Buren agreed, but, by that time, the matter had fallen under court jurisdiction.

Gedney and Meade of the Washington sued under salvage laws for a portion of the Amistad’s cargo, as did Green and Fordham. Ruiz and Montez sued separately. The district court trial in Hartford determined the Mendians’ papers to be forged. These were now former slaves entitled to be returned to Africa.

Antonio was ruled to have been a slave all along and ordered returned to Cuba. He fled to New York with the help of white abolitionists and lived out the rest of his days as a free man.

Fearing the loss of pro-slavery political support, President van Buren ordered government lawyers to appeal the case up to the United States Supreme Court. The government’s case depended on the anti-piracy provision of a treaty then in effect between the United States, and Spain.

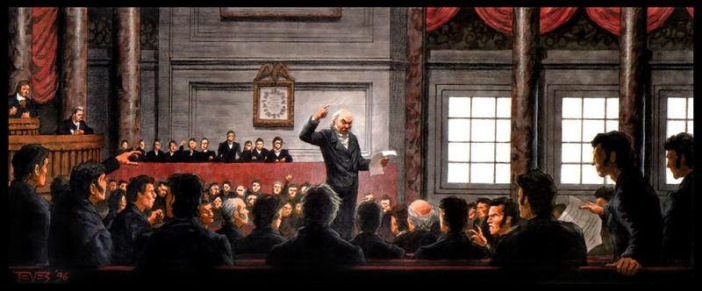

A former President, son of a Founding Father and eloquent opponent of ‘peculiar institution’ John Quincy Adams argued the case in a trial beginning on George Washington’s birthday, 1841.

In United States v. Schooner Amistad, the Supreme Court upheld the decision of the lower court 8-1, ruling that the Africans had been detained illegally and ordering them returned to their homeland.

Pro slavery Whig John Tyler was President by this time, refusing to provide a ship or to fund the repatriation. Abolitionists and Christian missionaries stepped in, 34 surviving Mendians departing for Sierra Leone on November 25, 1841 aboard the ship, Gentleman.

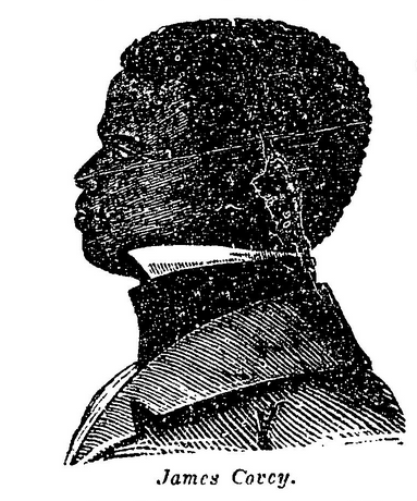

The Amistad story has been told in books and in movies and is familiar to many. One name perhaps not so familiar is that of James Benjamin Covey. James Covey was born Kaweli sometime around 1825, in what is now the the border region between of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. Kidnapped in 1833 and taken aboard the Segundo Socorro, Kaweli was an illegal slave when the vessel was seized by the Royal Navy.

Kaweli went to school for five years in Bathurst, Sierra Leone, where he took the name of James Benjamin Covey. Joining the Royal Navy, Covey participated in the capture of several illegal slave ships.

Hired on as live interpreter, James Covey was to play a crucial role in the Medians’ trial before the Supreme Court. He would also accompany the 34 on their return to the African continent.

James Covey, aka Kaweli, was going home.

‘They all have Mendi names and their names all mean something… They speak of rivers which I know. They sailed from Lomboko… two or three speak different language from the others, the Timone language… They all agree on where they sailed from. I have no doubt they are Africans.’ – James Benjamin Covey

Gentleman landed in Sierra Leone in January 1842, where some of the Africans helped establish a Christian mission. Most including Joseph Cinque himself returned to homelands in the African interior. One survivor, a little girl when it all started by the name of Margru, returned to the United States where she studied at Ohio’s integrated Oberlin College, returning to Sierra Leone as the Christian missionary Sara Margru Kinson.

In arguing the case, President Adams took the position that no man, woman or child in the United States could ever be sure of the “blessing of freedom” if the President could hand over free men on the demand of a foreign government.

A century and a half later later President Bill Clinton, Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder and AG Janet Reno orchestrated the kidnap of six-year-old Elián González at gunpoint, returning him to Cuba over the body of the mother who had drowned bringing her boy to freedom.

The Stuart King James had judges riding into the countryside once a year to hear cases, saving many of his subjects the arduous journey to London. The custom carried “across the pond” and, from the earliest days of the American colonies, judges could be found “riding the circuit”.

The Stuart King James had judges riding into the countryside once a year to hear cases, saving many of his subjects the arduous journey to London. The custom carried “across the pond” and, from the earliest days of the American colonies, judges could be found “riding the circuit”.

In 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sought to increase the number of justices to 15. Then as now, the court was sharply divided along ideological lines, consisting of a four member conservative majority called the “four horsemen”, three liberals dubbed the “three musketeers” and two “swing votes”.

In 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sought to increase the number of justices to 15. Then as now, the court was sharply divided along ideological lines, consisting of a four member conservative majority called the “four horsemen”, three liberals dubbed the “three musketeers” and two “swing votes”. There have been fewer justices in Supreme Court history than you might think. The recent passing of Antonin Scalia made way for only number 113.

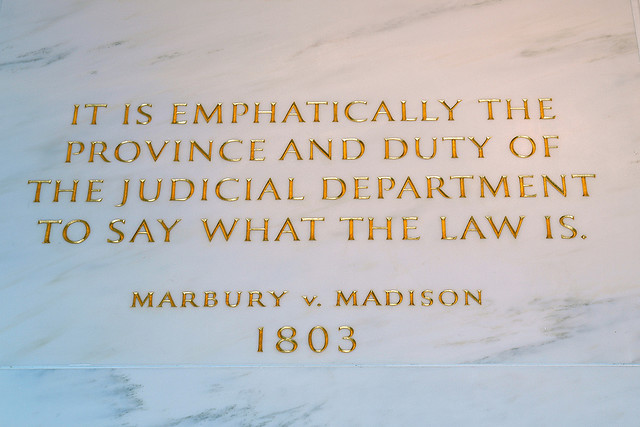

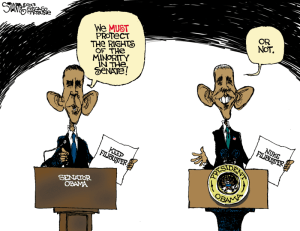

There have been fewer justices in Supreme Court history than you might think. The recent passing of Antonin Scalia made way for only number 113. “There are some who believe that the president, having won the election, should have complete authority to appoint his nominee, that once you get beyond intellect and personal character, there should be no further question as to whether the judge should be confirmed. I disagree with this view”. The filibuster was joined by Senators Kennedy, Leahy, Durbin, Salazar, and Baucus.

“There are some who believe that the president, having won the election, should have complete authority to appoint his nominee, that once you get beyond intellect and personal character, there should be no further question as to whether the judge should be confirmed. I disagree with this view”. The filibuster was joined by Senators Kennedy, Leahy, Durbin, Salazar, and Baucus. Senator Schumer once said, “We have three branches of government. We have a house, we have a senate, we have a president.” He got that wrong, but he was part right. We have three co-equal branches in our government, each having specific responsibilities as laid out in the Constitution.

Senator Schumer once said, “We have three branches of government. We have a house, we have a senate, we have a president.” He got that wrong, but he was part right. We have three co-equal branches in our government, each having specific responsibilities as laid out in the Constitution.

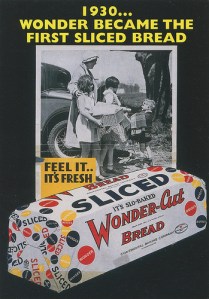

The project almost ended in a fire in 1917, when the prototype was destroyed along with the blueprints. Rohwedder soldiered on, by 1927 he had scraped up enough financing to rebuild his bread slicer.

The project almost ended in a fire in 1917, when the prototype was destroyed along with the blueprints. Rohwedder soldiered on, by 1927 he had scraped up enough financing to rebuild his bread slicer.

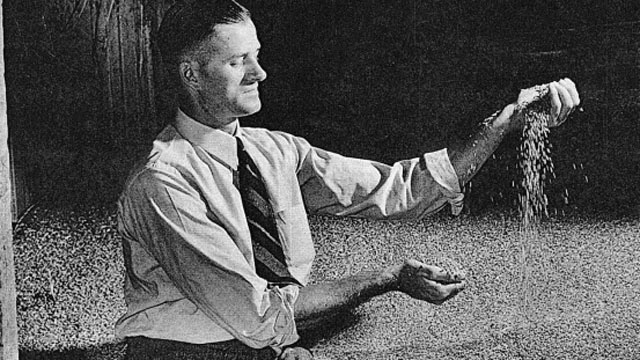

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it. The Federal District Court sided with the farmer, but the Federal government appealed to the US Supreme Court, arguing that, by withholding his surplus from the interstate wheat market, Filburne was effecting that market, and therefore fell under federal government jurisdiction under the commerce clause.

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it. The Federal District Court sided with the farmer, but the Federal government appealed to the US Supreme Court, arguing that, by withholding his surplus from the interstate wheat market, Filburne was effecting that market, and therefore fell under federal government jurisdiction under the commerce clause. government had a billion bushels of wheat stockpiled at the time, about two years’ supply, and the amount of steel saved by not making bread slicers has got to be marginal, at best.

government had a billion bushels of wheat stockpiled at the time, about two years’ supply, and the amount of steel saved by not making bread slicers has got to be marginal, at best.

You must be logged in to post a comment.