Come join me for a moment, in a thought experiment. A theater of the mind.

Imagine. Two nuclear superpowers, diametrically opposed, armed to the teeth and each deeply distrustful of the other. We’re talking here, about October 1962. The Cuban Missile Crisis. Now imagine at the height of the standoff, a misunderstanding leads some fool to push the button. The nuclear first strike is met with counterattack and response in a series of ever-escalating retaliatory launches.

You’ve seen enough of human nature. Counterattacks are all but inevitable, right? Like some nightmare shootout at the OK corral, only this one is fought with kiloton-sized weapons. Cities the world over evaporate in fireballs. Survivors are left to deal with a shattered, toxic countryside and nuclear winter, without end.

Are we talking about an extinction event? Possibly. Terrible as it is, it’s not so hard to imagine, is it?

In 1947, members of the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists envisioned a “Doomsday Clock”. A symbolic clock face, dramatizing the threat of global nuclear catastrophe. Initially set at seven minutes to midnight, the “time” has varied from seventeen minutes to two.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 didn’t make it onto the doomsday clock. Those 13 days went by far too quickly to be properly assessed. And yet, the events of 62 years ago brought us closer to extinction than at any time before or since.

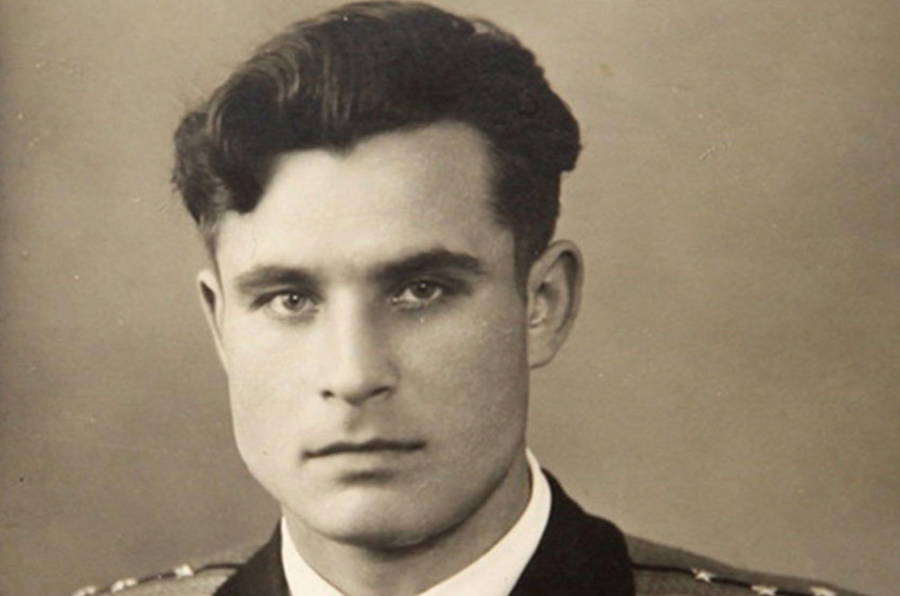

On this day in 1962, an unsuspecting world stood seconds away from the abyss. The fact that we’re here to talk about it came down to one man, Vasili Arkhipov. Many among us have never heard his name. Chances are very good that we can thank him for our lives.

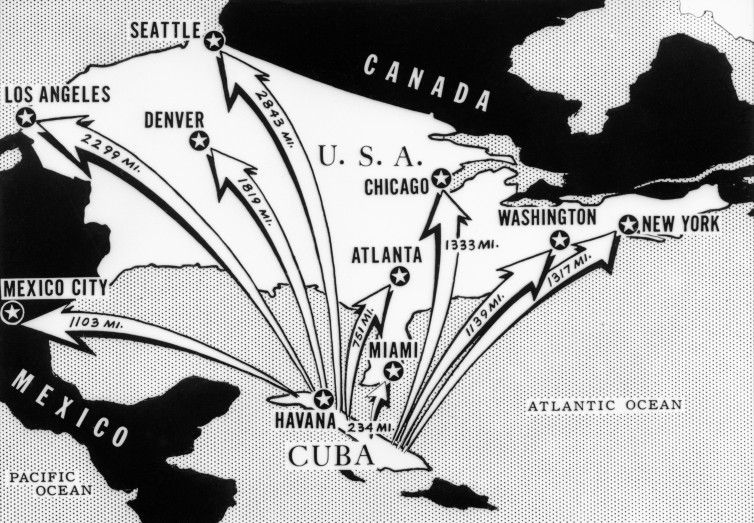

As WW2 gave way to the nuclear age, Cold War military planners adopted a policy of “Deterrence”. “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD). Soviet nuclear facilities proliferated across the “Eastern Bloc”, while US nuclear weapons dispersed across the NATO alliance. By 1961 some 500 US nuclear warheads were installed in Europe, from West Germany to Turkey, Italy to Great Britain.

Judging President Kennedy weak and ineffective, communist leaders made their move in 1962, signing a secret arms agreement in July. Medium-range ballistic missiles with a range of 2,000 miles were headed to the Caribbean basin.

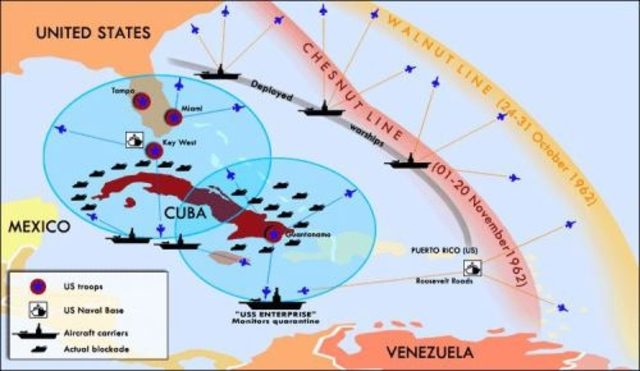

By mid- October, US reconnaissance aircraft revealed Soviet ballistic nuclear missile sites under construction Cuba. 90 miles from American shores. President John F. Kennedy warned of the “gravest consequences”, ordering a blockade of the island nation. Relations turned to ice as Soviet military vessels joined the standoff.

Tensions dialed up to 11 on October 27, when USAF Major Rudolph Anderson’s U-2 reconnaissance aircraft was shot down over the village of Veguitas. His body still stapped into his ejection seat.

The US Navy practiced a submarine attack protocol at that time, called “hunt to exhaustion”. Anatoly Andreev described what it was like to be on the receiving end:

“For the last four days, they didn’t even let us come up to the periscope depth … My head is bursting from the stuffy air. … Today three sailors fainted from overheating again … The regeneration of air works poorly, the carbon dioxide content [is] rising, and the electric power reserves are dropping. Those who are free from their shifts, are sitting immobile, staring at one spot. … Temperature in the sections is above 50 [122ºF].”

I’m not sure I could think straight under conditions like that.

On the 27th, US Navy destroyers began to drop depth charges. This was not a lethal attack, intending only to bring the sub to the surface. Deep under the water, captain and crew had no way of knowing that. B-59 had not been in contact with Moscow for several days. Now depth charges were exploding to the left and right. Captain Valentin Savitsky made his decision. Convinced that war had begun, the time had come for the “special weapon”. “We’re gonna blast them now!,” he reportedly said. “We will die, but we will sink them all – we will not become the shame of the fleet.” Political officer Ivan Maslennikov concurred. Send it.

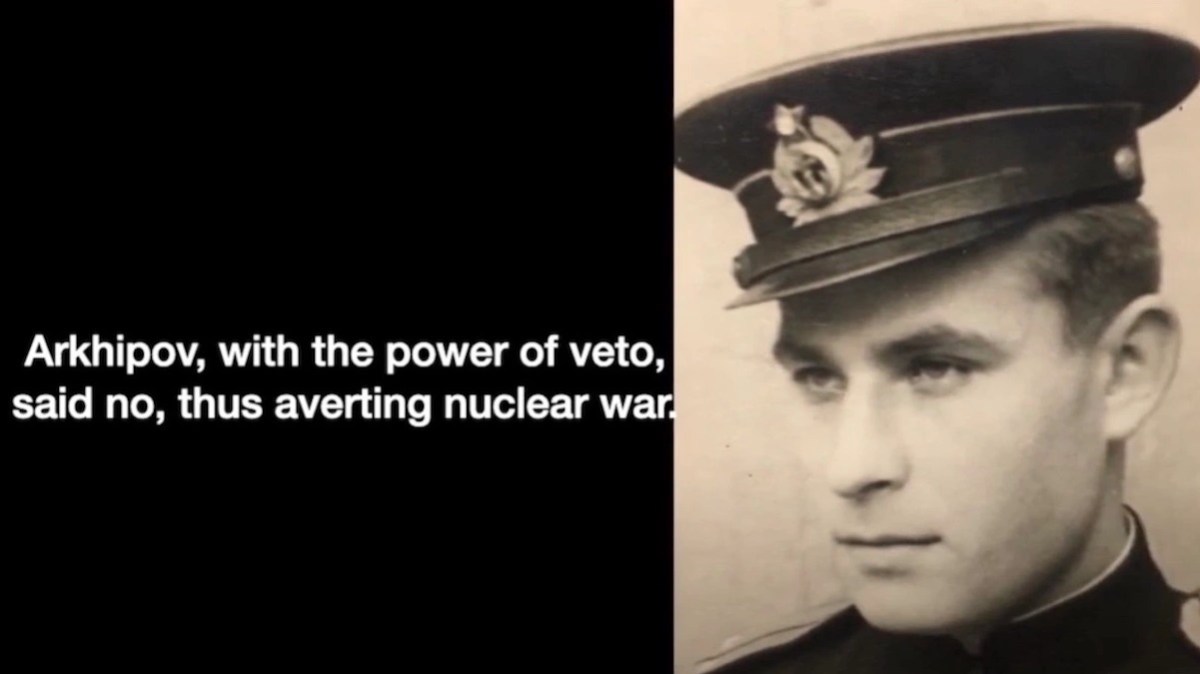

On most nuclear-armed Soviet submarines, two signatures were all that was needed. With Chief of (submarine fleet) Staff officer Vasili Archipov on board, the decision required approval by all three senior officers. To Archipov, this didn’t feel like a “real” attack. What if they’re only trying to get us to the surface?

Archipov said no.

Perhaps it was his role in averting disaster aboard the nuclear-powered submarine K-19, the year before. Maybe it was his calm, unflappable demeanor when Captain Savitsky had clearly “lost his temper”. Somehow, Archipov was able to keep his head together under unimaginable circumstances and convince the other two. B-59 came to the surface to learn that, no. World War III had not begun after all.

The submarine went quietly on its way. Kruschev announced the withdrawal of Soviet missiles the following day. The Cuban Missile Crisis was over.

These events wouldn’t come to light for another 40 years.

B-59 crewmembers were criticized on returning to the Soviet Union. One admiral told them “It would have been better if you’d gone down with your ship.”

Vasily Aleksandrovich Arkhipov retired from the submarine service in 1988 and died, ten years later. Cause of death was kidney cancer, likely the result of radiation exposure sustained during the K-19 incident, back in 1961.

Lieutenant Vadim Orlov was an intelligence officer back in 1962, onboard the B-59. In 2002, then Commander Orlov (retired) gave Archipov full credit for averting nuclear war. Former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara said in 2002 “We came very, very close, closer than we knew at the time.” Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. was an advisor to President Kennedy. “This was not only the most dangerous moment of the Cold War”, he said. “It was the most dangerous moment in human history.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.