From the time of Lewis and Clark, a growing nation expanded ever westward. First came the trappers and the traders. In 1834, merchant Nathaniel Wyeth led the first religious group westward along what would become the Oregon Trail. In 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold at a place called Sutter’s Mill. Countless prospectors swelled the ranks of homesteaders flooding ever westward. The California Gold Rush was on.

That same year, the Postal Department awarded a contract to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to deliver mail to the western territories. Under the contract, a letter would ship south from New York, transferred by horseback and rail across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico before returning to sea, destined for San Francisco. The process required three to four weeks under the best of circumstances, but it was more reliable than the old stage coach.

California became the 31st state in 1850. Ten years later some 380,000 people lived there. With coast-to-coast rail still years away, simmering tensions hurtling the nation toward Civil War proved the new system inadequate, even as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important.

Businessmen William Russell, Alexander Majors and William B. Waddell were in the shipping business, employing some 75,000 oxen, thousands of wagons and 6,000 men. One of those was the pioneer, future banker and Mayor of el Paso, Charles Robert Morehead. With experience running wagon trains through Wyoming and Utah, several attacked by Indians, Morehead was dispatched to Washington DC to meet with President Hames Buchanan. The subject, a proposed relay carrying mail to the west and back. A Pony Express.

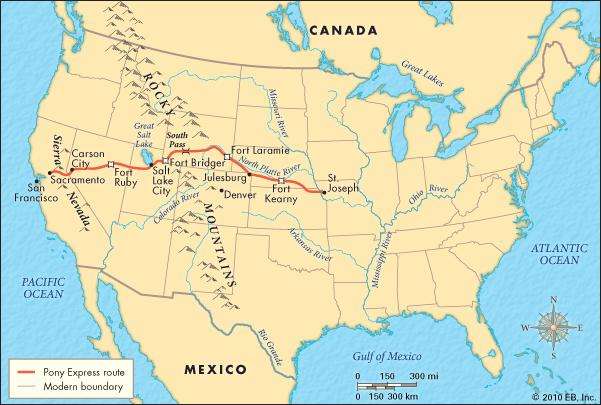

The Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company officially opened on April 3, 1860, horse-and-rider relays carrying letters the 1,966-mile distance from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California, and back.

Individual riders covered 75 – 100 miles at a time changing horses every 10-15 miles, at relay stations. Westbound delivery was compressed from weeks to ten days, on average. Riders carrying President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address covered the run in 7 days, and 17 hours.

Alone in a wilderness of bandits and sometimes hostile natives, riders traveled around the clock, their way lit only by lighting, or the light of the moon. In May 1860, 20-year old Robert “Pony Bob” Haslam finished a 75-mile run only to learn his replacement, as terrified of Paiute Indians, who’d been attacking stations along the way. Jumping on a fresh horse, Haslam encountered another station burned out by Paiutes. Pony Bob covered 370 miles in 40 hours before it was over, a Pony Express record.

Six riders died along the way, but even that wasn’t the most dangerous job. Livestock stations were little more than dirt floor hovels in remote locations with corrals for horses. Stationery and unmoving, livestock handlers were constantly at risk of ambush by desperados, and raiding Indians. In 18 months as many as 16 stock hands lost their lives.

80 to 100 riders aged 11 to 40 covered some 650,000 miles before it was over, delivering some 35,000 pieces of mail for an average of $100-$150 per month. Riders themselves were required to weigh 125-pounds or less and swear out the following oath, on pain of termination:

“I, (name), do hereby swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement, and while I am an employee of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, I will, under no circumstances, use profane language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God.”

Oath sworn by Pony Express Riders

Costs started out at $5.00 per ½ ounce and dropped to $1.00 per ½ ounce, after the introduction of a newer, lighter-weight paper. Even so, $5.00 in 1860 is equal to $130 today. The system was a financial disaster.

In the 19th century, the Pony Express was to the old methods as email is to snail mail. Even so, the system never did turn a profit. Far too expensive for ordinary people, the Pony Express carried mostly newspaper reports, business documents and government dispatches. For everyone else, the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Co. (C.O.C.&P.P.) stood for “Clean Out of Cash & Poor Pay!”

An expensive stopgap leading to the first transcontinental telegraph, the founders declared bankruptcy in only 18 months. The Pony Express came to a halt 18 months after it began, ending service in October 1861.

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important.

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important. The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system.

The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system. The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

You must be logged in to post a comment.