A lot can happen in eight years. Like when your preschooler comes home one day, and he’s ready for high school. Eight years after that your little bundle of joy is a college graduate and headed for medical school. It’ll take another eight years or so to become a doctor, depending on the specialty.

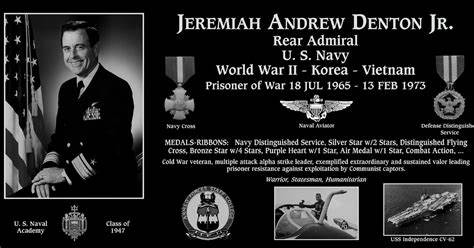

As a POW, Jeremiah Denton endured eight years in a brutally harsh captivity punctuated by daily abuse and frequent torture sessions, and went on to become a United states Senator.

His story deserves to be told.

Jeremiah Denton had already compiled an impressive resume when he slid into the cockpit of the A-6A Intruder attack aircraft on July 18, 1965.

Entering the United States Naval Academy in 1943, Denton joined an “accelerated class” to graduate in June 1946, along with future President of the United Sates, Jimmy Carter. Then came Armed Forces Staff College, a Master of Arts in International Affairs from George Washington University and the Naval War College, where Denton’s thesis revolutionized naval tactics earning top honors, including the prestigious President’s Award, in 1964.

Get an education or you’ll get stuck…how was that again…Mister Kerry?

Then it was July 18, 1965. For Jeremiah Denton, that was the day when everything changed.

While serving as a naval aviator, Commander Denton was leading a 28-aircraft bombing mission over North Vietnam, along with Bombardier/Navigator LTJG Bill Tschudy. The pair was forced to bail out when one of their own Mark 82 bombs exploded prematurely, sending the A-6A Intruder spinning out of control.

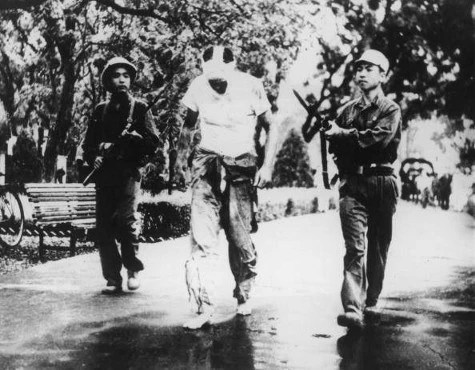

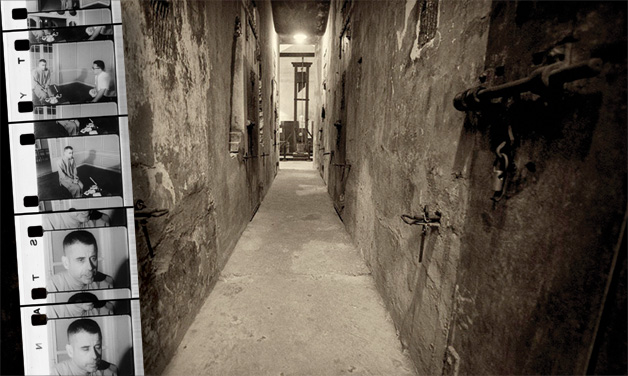

The two were quickly captured and brought to a colonial prison the French used to call, La Maison Centrale. The Vietnamese called this place Hỏa Lò, the name translating as “fiery furnace”. Some Americans called it the Hell Hole but for most, mocking their captors was a technique that helped them survive. They called this place, the “Hanoi Hilton”.

“They beat you with fists and fan belts. They warmed you up and threatened you with death. Then they really got serious and gave you something called the rope trick.”

Jeremiah Denton

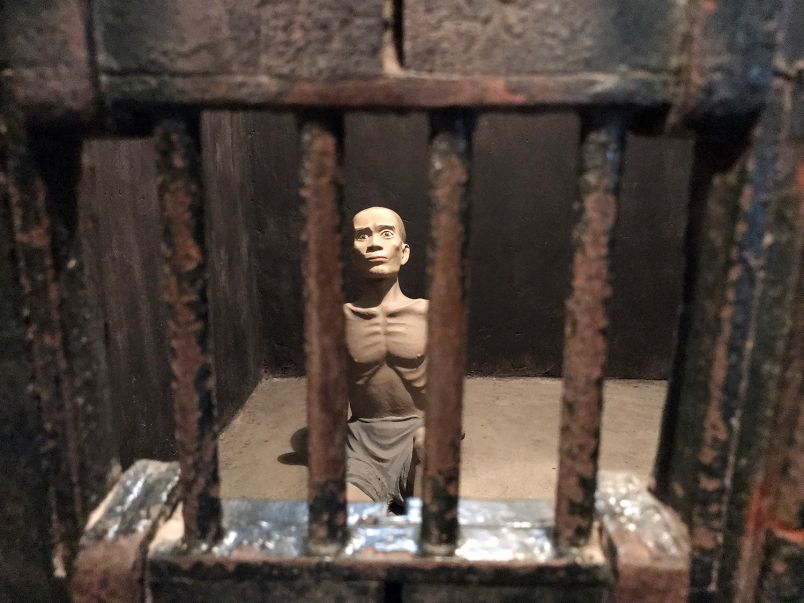

Over nearly eight years of captivity, Denton, Tschudy and others endured daily abuse up to and including outright torture. Torments unimaginable but for the most sadistic among us. Shackles on the floor meant for far smaller men caused Americans’ hands to turn black. Lice and cockroaches joined with rats and all manner of vermin to prey on men shackled to the floor, forced to live in their own excrement as they slowly, starved.

Denton endured eight years of these stinking, fetid cells including periods of solitary confinement, locked day and night in a sweltering box and shackled to the floor of an iron box, measuring 3-feet by nine..

Over 700 Americans were held captive by enemy forces over roughly ten years during the war in Vietnam. 114 did not survive. One of them went on to run unsuccessfully, for President. He can tell you better than I can, what it was like.

And then there were the torture sessions. Let Denton tell his own story about an episode with one guard, he and his fellow POWs called Mickey Mouse.

“Having beaten them in my last two torture sessions in 1966, I thought I could do it again. In an effort to deter the punishment, I wrote Mickey Mouse a note reminding him of my previous success, and said that if they were determined to torture me, they would have to torture me to death. That was a mistake. It was a pledge I couldn’t keep.

The next stage was rear cuffs and leg irons. A guard dragged me around the rough cement floor until the leg cuffs began tearing into my ankles. He jerked me left and right, lifted me by the rear handcuffs – the same mess all over again for hours. Then I was left on the floor for a day.

Mickey Mouse gave me one more chance to write the letter, and again I refused.

In the months since my last torture, the Vietnamese had developed a rig that was unknown to me, and it was the perfect answer to my ability to take pain until passing out. As soon as Mickey Mouse left the room, a guard slammed open the door, and held out a rope and a four-and-a-half-foot pole, pointed at one end.

Two more guards came into the room, and the three of them began tying my wrists and lower forearms together in front of me. They forced my elbows apart and forced my knees between them, and pushed the pole through the hole created by my elbows and knees. Then they tipped me back on my spine and propped my feet on an overturned stool so that my feet were raised about a foot off the ground.

In essence, I was in the fetal position, my thighs pressed against my chest so tightly that I could hardly breathe. My body was tipped at such an angle that most of my weight was on the tip of my spine. The pole was the key to the rig. If the rig was properly tied, I would pass out eventually and fall on my side; the end of the pole would hit the floor and slide out of the rig, easing the pressure on my arms and restoring circulation. The pain that came with the blood circulation would bring me back to consciousness; thus the prisoner couldn’t beat the rig by passing out.

“As a POW in the Hanoi Hilton, I could recall nothing from military survival training that explained the use of a meat hook suspended from the ceiling. It would hang above you in the torture room like a sadistic tease — you couldn’t drag your gaze from it. During a routine torture session with the hook, the Vietnamese tied a prisoner’s hands and feet, then bound his hands to his ankles — sometimes behind the back, sometimes in front. The ropes were tightened to the point that you couldn’t breathe. Then, bowed or bent in half, the prisoner was hoisted up onto the hook to hang by ropes. Guards would return at intervals to tighten them until all feeling was gone, and the prisoner’s limbs turned purple and swelled to twice their normal size. This would go on for hours, sometimes even days on end.”

ex-POW, Sam Johnson

Over time, camaraderie became the key to survival. POWs learned to communicate. During his first four months in solitary confinement, Lt. Cmdr. Bob Shumaker noticed one particular inmate, regularly dumping his slop bucket. In a note scribbled out on a scrap of toilet paper and slipped under the door, Shumaker wrote, “Welcome to the Hanoi Hilton. If you get note, scratch balls as you are coming back.” The soldier did as asked and even wrote his own note, identifying himself as Air Force Captain Ron Storz.

POWs developed a tap code to warn about particularly sadistic guards, what to expect during interrogations and a hundred other things. They even tapped out jokes. A kick on the wall meant laughter. Air Force pilot Ron Bliss once said the Hanoi Hilton “sounded like a den of runaway woodpeckers.”

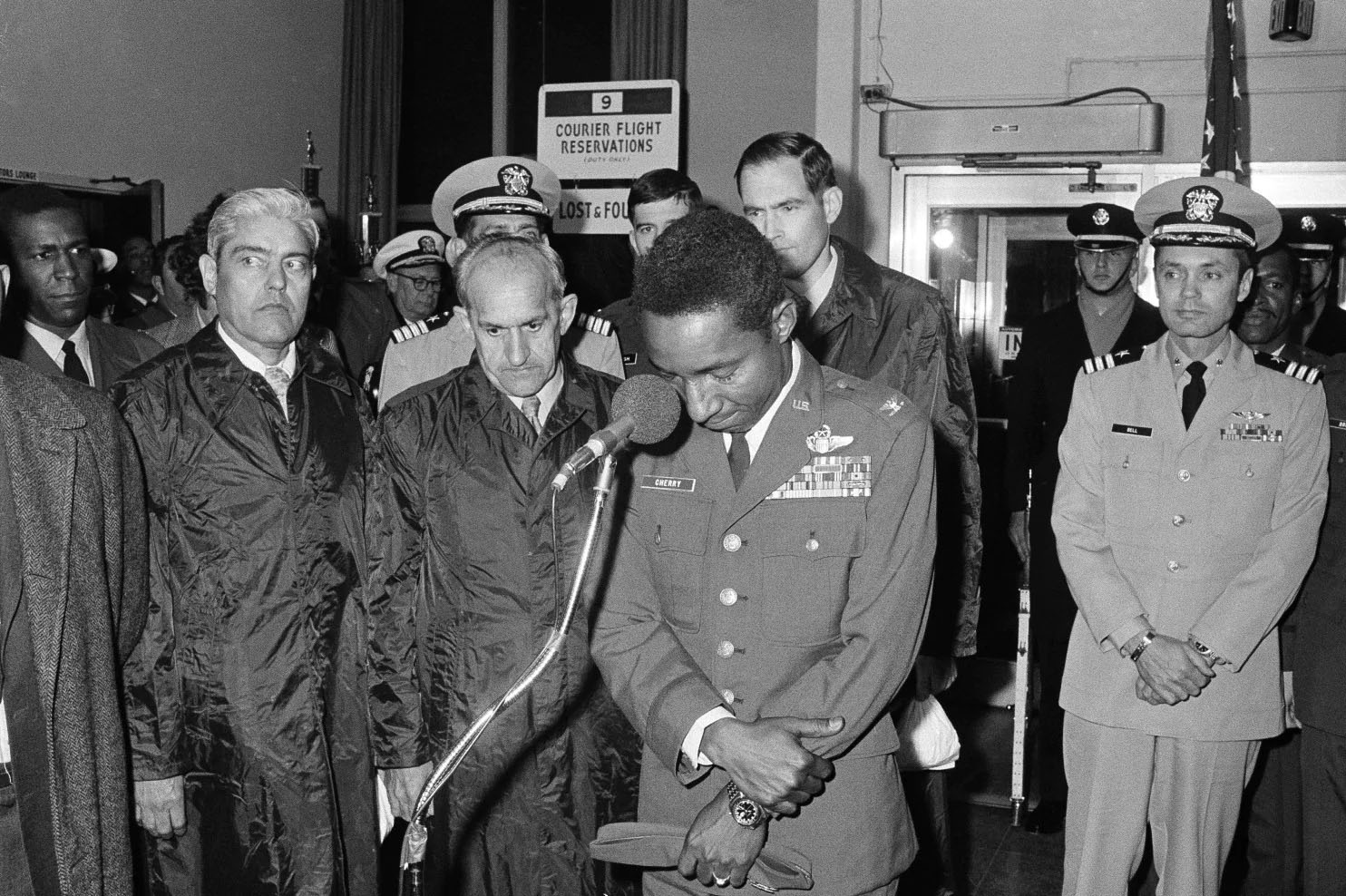

In this place each other, was all they had. “I guess they thought if they had a Southern white boy taking care of a black man” Porter Halyburton once told the Washington Post, “it would be the worst place for both of us,” Fred Vann Cherry turned out to be tougher than either man realized, at the time. “It turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to me, said Halyburton”.

Halyburton looked after his injured cellmate, changing the dressings on his infected wounds, feeding him, bathing him and watching over him. “He said I saved his life, and he saved my life. . . . Taking care of my friend gave my life some meaning that it had not had before.”

Humbert Roque “Rocky” Versace was a US Army Ranger who planned to become a priest of the Roman Catholic faith , who planned to come back to Vietnam to help the many orphans who had touched his heart. It was a bright and shining future, never meant to be.

Despite terrible injuries and incessant beatings Rocky would crawl away and escape, only to be beaten, yet again. So fluent was he in the tongue of his captors he would berate them and their communist ideology in their own language, humiliating his captors in front of villagers.

Even from solitary confinement Rocky would belt out words of inspiration to his fellow prisoners, sung to the tune of popular songs. Finally his guards had had enough. Rocky Versace was murdered in cold blood and later earned the Medal of Honor, for his defiance.

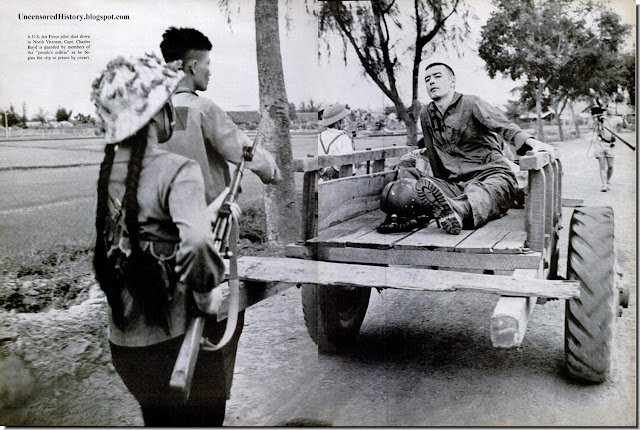

In July 1966, Denton and 50 fellow POWs were bound and paraded through the streets of Saigon, beaten and kicked by North Vietnamese civilians, along the way.

And yet some acts of defiance, astonishing even to contemplate. Summoned to appear to appear in a propaganda film to attest to his “good treatment”, Vice Admiral James Stockdale battered his own face with a stool and cut his hands and wrists, rather than appear in such a production. The man was a leader and an inspiration to his fellow captives, for which he too was awarded the Medal of honor.

“We had a war to fight and were committed to fighting it from lonely concrete boxes. Our very fiber and sinew were the only weapons at our disposal. Each man’s values from his own private sources provided the strength enabling him to maintain his sense of purpose and dedication. They placed unity above self. Self-indulgence was a luxury that could not be afforded.”

Vice Admiral James Stockdale

Jeremiah Denton was summoned to produce such a video. Feigning trouble with the bright lights, he blinked out the word T-O-R-T-U-R-E in Morse code.

The stunt earned him no end of abuse when his communist captors figured out what he had done but by that time, it was too late. Somehow the tape made it out. It was the first confirmation of long-standing rumors that American POWs were in fact, being tortured.

Civilian pilot Ernest Cary Brace was the longest serving POW, at 7 years, 10 months and 7 days. Brace’s wife Patricia assumed he was dead and remarried, a fact he learned at the processing station, following his release.

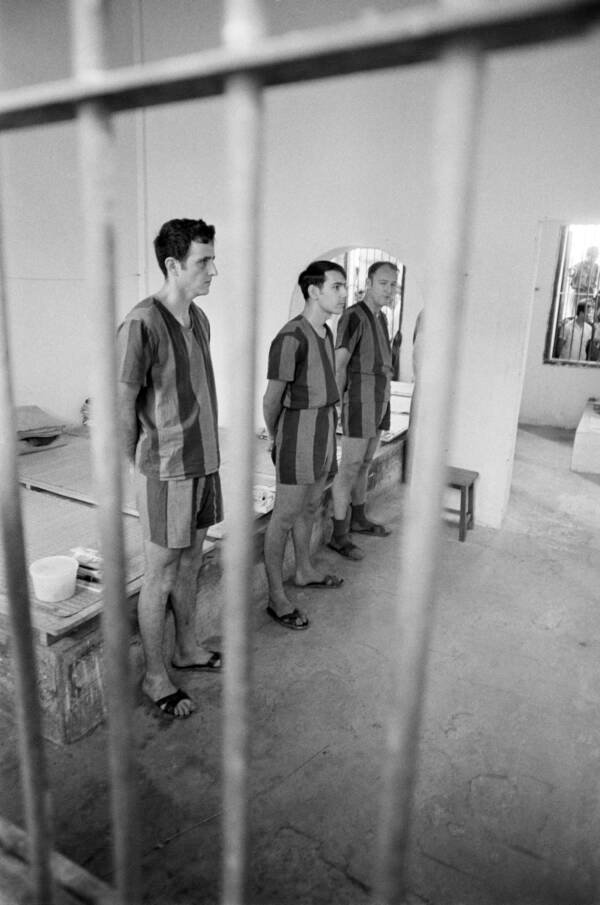

With the war winding to a close, Tschudy and Denton were released on February 12, 1973. The release was part of “Operation Homecoming”, the return of some 591 POWs following the Paris Peace Accords.

How you or I would endure even a day of such a place is a question, without an answer. Many of them are gone now, those years of abuse surely robbing many of their later years. And yet endure they did.

Jeremiah Denton wrote a book about his experiences called When Hell was in Session, if you want to learn more. James Stockdale, John McCain, Denton and others went on to further service, to the nation. There are those who will tell you some of our POWs, Never came home. All of them, every one, have earned the right to be remembered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.