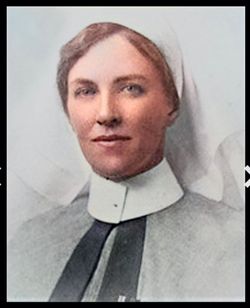

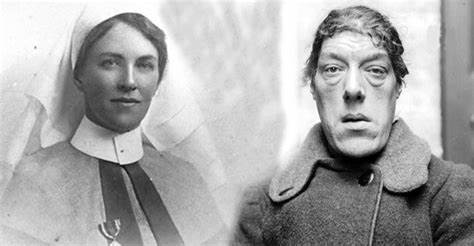

Mary Ann Webster arrived in this world on December 20, 1874, borne of a working class family in the East London township of Plaistow. Hers was a normal childhood, no different than any of her seven siblings. At the age of 20, she qualified to become a nurse.

If the last three years have taught us anything about the nursing profession, it’s a heartfelt respect for those who care for others. Sometimes, at no small risk to themselves.

Today we revere the profession, but such was not always the case. No less a person than the “mother of modern nursing” Florence Nightingale once described the job, as being for ‘those who were too old, too weak, too drunken, too dirty, too stupid or too bad to do anything else’.

When Mary Ann Webster joined the profession, it certainly wasn’t for the money.

Then came the day Mary Ann met a farmer named Thomas Bevan. The couple fell in love and and were wed in 1903. Over time, the union produced four children. Theirs was a happy marriage until that day in 1914, when Thomas entered their small cottage and dropped dead at her feet.

A terrible storm was gathering in 1914 Europe, about to plunge a continent into war. Left without her principle source of support with four children to feed Mary Ann Bevan faced a terrible storm of her own, even then taking place within her own body.

Acromegaly is a neuroendocrine disorder, known to cause excess growth hormones in the body.

Usually caused by a non-malignant tumor on the pituitary gland, Acromegaly results in gigantism when the condition begins before puberty. If you’re a professional wrestling fan, think of the Punjabi wrestler “The Great Khali”, or Andre the Giant.

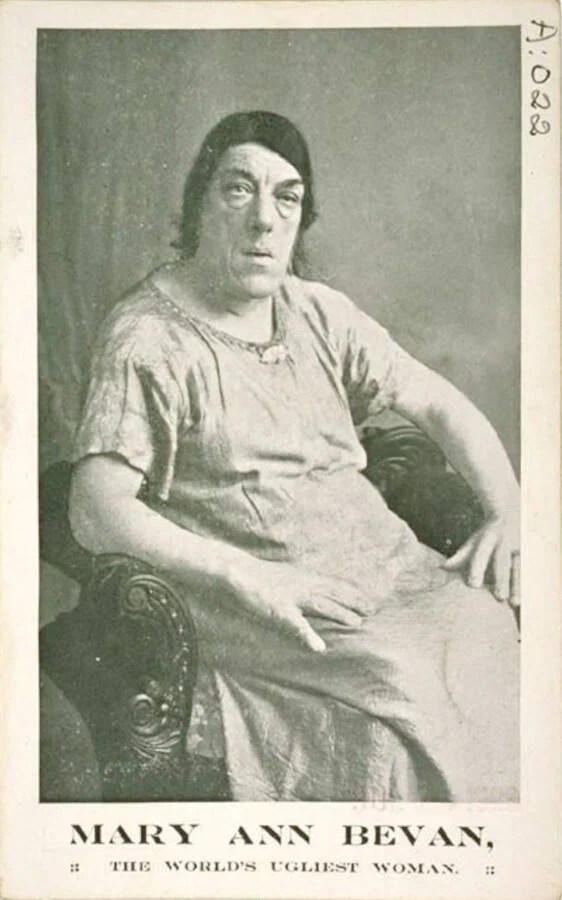

When contracted in adulthood, Acromegaly results in a thickening of the skin, enlargement of extremities and facial features and a deepened, “husky” voice accompanied by severe headaches and joint pain.

Today the condition can be dealt with, if detected early. Early 20th century medicine offered no options for the treatment of such a disease.

In a world beset by the catastrophe of World War I, Mary Ann Bevan was left with four children to feed, no husband and a rapidly developing personal horror about to render her own appearance, a thing of the past.

As the condition advanced, coworkers and patients alike were at first put off by her changing facial features and then disgusted. Reviled and alone work went from difficult to impossible, leaving the young widow nothing but odd jobs to support herself and her children.

Then one day the newspaper arrived, in 1920:

Wanted: The Ugliest Woman. Nothing Repulsive Maimed or Disfigured. Good Pay Guaranteed and Long Engagement for Successful Applicant. Send Recent Photo.

Newspaper ad

If you’ve ever thought to yourself that people seem judgmental in the age of social media, you’re not alone. You’re not wrong either, but that’s nothing new. People have flocked to gawk at and ridicule “freaks of nature” going back to medieval days, if not before. In the court of King Charles I, two conjoined brothers called Lazarus and Joannes Baptista Colloredo were a source of mean-spirited entertainment. 2-foot 5-inch Matthias Buchinger amazed 18th century crowds in England and Ireland with feats of magic, art and music, despite having no hands and no feet.

So minutely detailed was Buchinger’s calligraphy the locks of his own hair seen in the self-portrait above, are actually 7 biblical psalms and the Lord’s Prayer. But I digress.

This sort of voyeurism came to a pinnacle in the form of the “Freak Show” of late 19th and early 20th century United States and England. Which brings us back to Mary Ann Bevan. The man behind the newspaper advert was Claude Bartram, agent for the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Allthatsinteresting.com writes: “She was paraded alongside other notable sideshow acts including Lionel, the Lion-Faced Man, Zip the “Pinhead,” and Jean Carroll, the Tattooed Lady. Dreamland visitors were invited to gawk at the 154 pounds she carried on her 5′ 7″ frame, as well as her size 11 feet and size 25 hands. Bevan bore the humiliating treatment calmly. “Smiling mechanically, she offered picture postcards of herself for sale,” thus securing sufficient money for herself and for her children’s education”.

What it is to appear in a carnival freak show, I leave to the imagination. The sneers and taunts, the comments… Mary Ann found romance in later life with a giraffe keeper, remembered only as Andrew. She even agreed to a beauty makeover one time, at a New York salon. With her face made up complete with a massage, new hairdo and manicure, one of the snottier commenters asserted: ”the rouge and powder and the rest were as out of place on Mary Ann’s countenance as lace curtains on the portholes of a dreadnought.”

Mary Ann herself looked in the mirror and sighed saying simply, “I guess I’ll be getting back to work.”

Mary Ann Bevan performed at Coney Island until the day she died on December 26, 1933. She was only 59. She is buried at Southeast London’s Brockley and Ladywell Cemetery.

Save for aficionados of the American sideshow circuit she faded from history after that, until 2000. The Hallmark greeting card company used her image in an unfunny and cruel joke about blind dates, raising no small storm of criticism from the public. To their credit, Hallmark removed the card from the market.

If there is a last word on the subject of personal appearance, let it go to Mary Ann herself. During two years of performing in New York and enduring the humiliation, sneers and derision of strangers the young mother more than provided for her family, earning the equivalent of 1.6 million dollars in today’s value.

Captured at Spotsylvania early in 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry soldier James Tyner was a POW at this time, languishing in “Hellmira” – the fetid POW camp at Elmira, New York. “The Andersonville of the Northern Union.”

Captured at Spotsylvania early in 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry soldier James Tyner was a POW at this time, languishing in “Hellmira” – the fetid POW camp at Elmira, New York. “The Andersonville of the Northern Union.”

The “pumpkin flood“ of 1903 scoured the rail line, uncovering many of the dead and carrying away their mortal remains. It must have been a sight – caskets moving with the flood, bobbing like so many fishing plugs, alongside countless numbers of that year’s pumpkin crop.

The “pumpkin flood“ of 1903 scoured the rail line, uncovering many of the dead and carrying away their mortal remains. It must have been a sight – caskets moving with the flood, bobbing like so many fishing plugs, alongside countless numbers of that year’s pumpkin crop.

You must be logged in to post a comment.