In the 5th century, the migration of warlike Germanic tribes across northern Europe culminated in the destruction of the Roman Empire in the west. That much is relatively well known, but the “why”, is not. What would a people so fearsome as to bring down an empire, have been trying to get away from?

The Roman Empire was split in two in the 5th century and ruled by two separate governments. Ravenna, in northern Italy, became capital to the Western Roman Empire in 402 and would remain so until the final collapse, in 476. In the east was Constantinople, seat of the Byzantine empire and destined to go on another thousand years. That would come to an end in 1453 at the hands of the 21-year-old Mehmed “The Conqueror’, 7th sultan of the ottoman Empire. Today we know this crossroads between east and west as Istanbul, but that must be a story, for another day.

Back to the 5th century vast populations moved westward from Germania, into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

The Huns.

Rome itself had mostly friendly relations with the Hunnic Empire, which stretched from modern day Germany in the west to Turkey and most of Ukraine, in the east. They were a nomadic people, mounted warriors all but born to the saddle whose main weapons were the bow, and the javelin. Often, Huns acted as mercenary soldiers, paid to fight on behalf of Rome.

Rome looked at such payments as just compensation for services rendered. To the Huns this was tribute. Tokens of Roman submission to the Hunnic Empire.

Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, described Rome’s problems with the Hun, succinctly. “They have become both masters and slaves of the Romans”.

Relations became strained between the two powers during the time of the Hunnic King Rugila, as his nephew the future King Attila, came of age.

Rugila’s death in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda, in control of the united Hunnic tribes. The following year, the brothers negotiated a treaty with Emperor Theodosius of Constantinople, giving the Byzantines time to strengthen the city’s defenses. This included the first sea wall, a structure the city would be forced to defend a thousand years later when even the Theodosian Wall could not stem the Islamic conquest of 1453.

The priest of the Greek church Callinicus wrote what happened next, in his “Life of Saint Hypatius”. “The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. … And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers“.

Bleda died sometime in 445 leaving Attila the sole King of the Huns. Relations with the Western Roman Empire had been relatively friendly, for a time. That changed in 450 when Justa Grata Honoria, sister of Emperor Valentinian, sought to escape a forced marriage to the former consul Herculanus. Honoria sent the eunuch Hyacinthus with a note to Attila, asking the king to intervene on her behalf. She enclosed her ring in token of the message’s authenticity. Attila took this to be an offer of marriage.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all, nothing more than a misunderstanding.

The King of the Huns wasn’t buying it and sent an emissary to Ravenna, to claim what was his. Attila demanded delivery of his “bride” along with a modest half of the empire, as dowry.

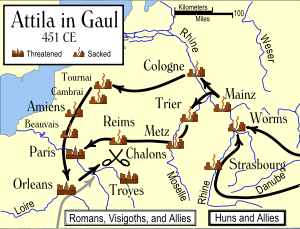

In 451, Attila gathered his vassals and began a march to the west. The Hunnic force was estimated to be half a million strong though that number is almost certainly exaggerated. The Romans hurriedly gathered an army to oppose them while the Huns sacked the cities of Mainz, Worms, Strasbourg and Trier.

Some 1,500 years later the headlines announced the impregnable city of Metz, had fallen to US 95th Infantry.

On April 7, 451 the streets of Metz ran red with the blood of the slain followed in quick succession by those of Cologne, Cambrai, and Orleans.

The Roman army, allied with the Visigothic King Theodoric I, finally stopped the army of Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, near Chalons. Some sources date the Battle of Chalons at June 20, 451, others at September 20. Even the outcome of the battle is open to interpretation. Sources may be found to support the conclusion that the battle was a Roman, a Gothic or a Hunnic victory.

Be that as it may it was a Pyrrhic victory in the end. Chalons was one of the last major military operations of the Roman Empire in the west. The Roman alliance had stopped the Hunnic invasion in Gaul, but the military might of Roman and Visigoth alike, was no more.

Attila would return to sack much of Italy in 452, this time razing Aquileia so completely that no trace of it was left behind. Legend has it that Venice was founded at this time when local residents fled the Huns, taking refuge in the marshes and islands of the Venetian Lagoon.

Attila himself died the following year at a wedding feast, celebrating his marriage to the beautiful young Ostrogoth, Ildico. She may have been yet another alliance bride weeping in her innocence, at the death of her newly wed husband. Or perhaps she was the assassin, come to settle some ancient blood feud between the Germanic peoples, and the Hun. The King of the Huns died in a drunken stupor as the result of a massive nosebleed, or possibly esophageal bleeding. This was not the first such event.

The last of the Hunnic Empire died with King Attila as he choked to death on his own blood. In 454 the Hunnic Empire was dismantled by a coalition of Germanic vassals following the Battle of Nedau.

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

You must be logged in to post a comment.