“Listen my children and you shall hear,

Of the midnight ride of”…Sybil Ludington.

Wait…What?

Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” began on the night of April 18, 1775. Revere was one of two riders, soon joined by a third, fanning out from Boston to warn of an oncoming column of “regulars”, come to destroy the stockpile of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon in Concord.

Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” began on the night of April 18, 1775. Revere was one of two riders, soon joined by a third, fanning out from Boston to warn of an oncoming column of “regulars”, come to destroy the stockpile of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon in Concord.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

William Tryon was the Royal Governor of New York, and long-standing advocate for attacks on civilian targets. In 1777, he was also a major-general of the provincial army. On April 25th, Tryon set sail for the Connecticut coast of Long Island Sound with a force of 1,800, intending to destroy Danbury.

Patriot Colonel Joseph Cooke’s small Danbury garrison was caught and quickly overpowered on the 26th, trying to remove food supplies, uniforms, and equipment. Facing little if any opposition, Tryon’s forces went on a bender, burning homes, farms and storehouses. Thousands of barrels of pork, beef, and flour were destroyed, along with 5,000 pairs of shoes, 2,000 bushels of grain, and 1,600 tents.

Patriot Colonel Joseph Cooke’s small Danbury garrison was caught and quickly overpowered on the 26th, trying to remove food supplies, uniforms, and equipment. Facing little if any opposition, Tryon’s forces went on a bender, burning homes, farms and storehouses. Thousands of barrels of pork, beef, and flour were destroyed, along with 5,000 pairs of shoes, 2,000 bushels of grain, and 1,600 tents.

Colonel Henry Ludington was a farmer and father of 12, with a long military career. A long-standing and loyal subject of the British crown, Ludington switched sides in 1773, joining the rebel cause and rising to command the 7th Regiment of the Dutchess County Militia, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

In April 1777, Ludington’s militia was disbanded for planting season, and spread across the countryside. An exhausted rider arrived at the Ludington farm on a blown horse, on the evening of the 26th, asking for help. 15 miles away, British regulars and a force of loyalists were burning Danbury to the ground.

The Dutchess County Militia had to be called up. The Colonel had one night to prepare for battle, and this rider was done. The job would have to go to Colonel Ludington’s first-born, his daughter, Sybil.

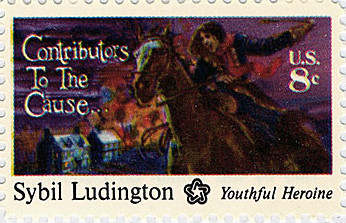

Born April 5, 1761, Sybil Ludington was barely sixteen at the time of her ride. From Poughkeepsie to what is now Putnam County and back, the “Female Paul Revere” rode across the lower Hudson River Valley, covering 40 miles in the pitch dark of night, alerting her father’s militia to the danger and urging them to come out and fight. She’d use a stick to knock on doors, even using it once, to fight off a highway bandit.

By the time Sybil returned the next morning, cold, rain-soaked, and exhausted, most of 400 militia were ready to march.

35 miles to the east of Danbury, General Benedict Arnold was gathering a force of 500 regular and irregular Connecticut militia, with Generals David Wooster and Gold Selleck Silliman.

Arnold’s forces arrived too late to save Danbury, but inflicted a nasty surprise on the British rearguard as the column approached nearby Ridgefield. Never outnumbered by less than three-to-one, Connecticut militia was able to slow the British advance until Ludington’s New York Militia arrived on the following day. The last phase of the action saw the same type of swarming harassment, as seen on the British retreat from Concord to Boston, early in the war.

Though the British operation was a tactical success, the mauling inflicted by these colonials ensured that this was the last hostile British landing on the Connecticut coast.

The British raid on Danbury destroyed at least 19 houses and 22 stores and barns. Town officials submitted £16,000 in claims to Congress, for which town selectmen received £500 reimbursement. Further claims were made to the General Assembly of Connecticut in 1787, for which Danbury was awarded land. In Ohio.

The Keeler Tavern in Ridgefield is now a museum. The British cannonball fired into the side of the building, remains there to this day.

At the time, Benedict Arnold planned to travel to Philadelphia, to protest the promotion of officers junior to himself, to Major General. Arnold, who’d had two horses shot out from under him at Ridgefield, was promoted to Major General in recognition for his role in the battle. Along with that promotion came a horse, “properly caparisoned as a token of … approbation of his gallant conduct … in the late enterprize to Danbury.” For now, the pride which would one day be his undoing, was assuaged.

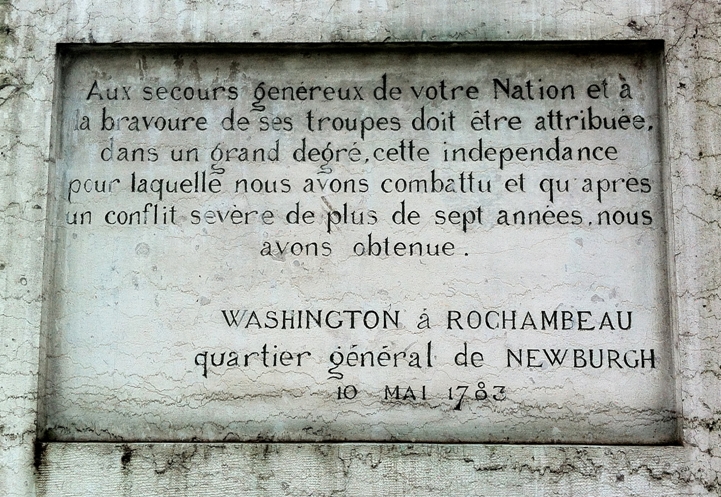

Henry Ludington would become Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington, and grandfather to Harrison Ludington, mayor of Milwaukee and 12th Governor of Wisconsin.

Gold Silliman was kidnapped with his son by a first marriage by Tory neighbors, and held for Nearly seven months at a New York farmhouse. Having no hostage of equal rank with whom to exchange for the General, Patriot forces went out and kidnapped one of their own, in the person of Chief Justice Judge Thomas Jones, of Long Island.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, including caring for her own midwife, who was brutally raped by English forces for denying them the use of her home. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells the story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives during the Revolution, as well as Mary’s own negotiations for her husband’s release from his Loyalist captors.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

Sybil Ludington received the thanks of family and friends, even George Washington, and then stepped off the pages of history.

Paul Revere’s famous ride would likewise have faded into obscurity, but for the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. 86 years later.

Declaration of Independence was even signed. With it were muskets, cannon, gunpowder, bombs, mortars, tents, and enough clothing for 30,000 men, traveling from French ports to the “neutral” Netherlands Antilles island of St. Eustatius.

Declaration of Independence was even signed. With it were muskets, cannon, gunpowder, bombs, mortars, tents, and enough clothing for 30,000 men, traveling from French ports to the “neutral” Netherlands Antilles island of St. Eustatius.

equipment, while de Grasse himself carried 500,000 silver pesos from Havana to help with the payroll and siege costs at the final Battle of Yorktown.

equipment, while de Grasse himself carried 500,000 silver pesos from Havana to help with the payroll and siege costs at the final Battle of Yorktown.

the “Regulars” sent to enforce the will of the Crown. Two years later, Sons of Liberty looted and burned the HMS Gaspee in Narragansett Bay, RI.

the “Regulars” sent to enforce the will of the Crown. Two years later, Sons of Liberty looted and burned the HMS Gaspee in Narragansett Bay, RI. That night, somewhere between 30 and 130 Sons of Liberty, some dressed as Mohawk Indians, boarded the three ships in Boston Harbor. There they threw 342 chests of tea, 90,000 pounds in all, into Boston Harbor. £9,000 worth of tea was destroyed, worth about $1.5 million in today’s dollars.

That night, somewhere between 30 and 130 Sons of Liberty, some dressed as Mohawk Indians, boarded the three ships in Boston Harbor. There they threw 342 chests of tea, 90,000 pounds in all, into Boston Harbor. £9,000 worth of tea was destroyed, worth about $1.5 million in today’s dollars. Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would record it as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would record it as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.