In the seventeenth century, conventional science held the “geocentric” view of the solar system, holding that our earth exists at the center of celestial movement with the sun and planetary bodies revolving around our little sphere.

The perspective was widely held but by no means unanimous. In the third century BC the Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos put the Sun in the center of the universe. Later Greek astronomers Hipparchus and Ptolemy agreed, refining Aristarchus’ methods to arrive at a fairly accurate estimate for the distance to the moon. Even so, theirs remained a minority view.

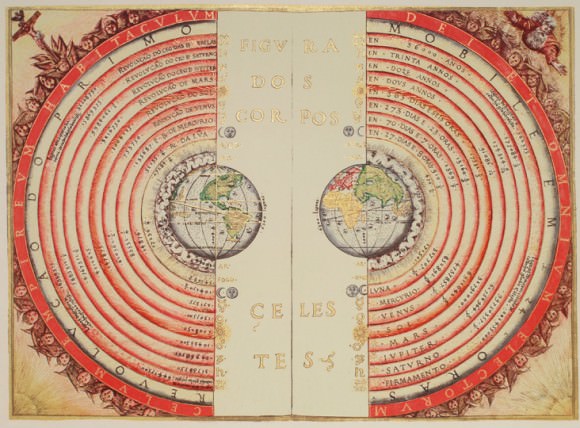

In the 15th century, Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus parted ways with the orthodoxy of his time describing a “heliocentric” model of the universe placing the sun, at the center. The Earth and other bodies, according to this model, revolved around the sun.

Copernicus wisely refrained from publishing such ideas until the end of his life, fearing to offend the religious sensibilities of the time. Legend has it that he was presented with an advance copy of his “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) on awakening on his death bed, from a stroke-induced coma. Copernicus took one look at his book, closed his eyes and never opened them again.

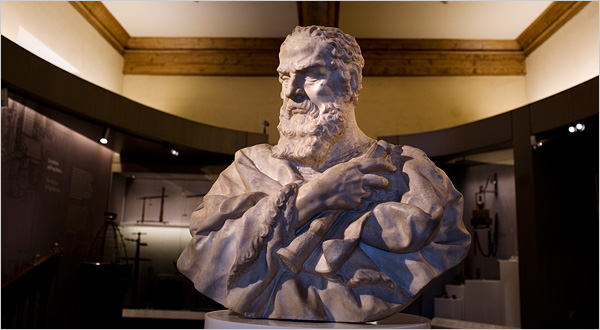

The Italian physicist, mathematician, and astronomer Galileo Galilei came along about a hundred years later. The “Father of Modern Observational Astronomy”, Galileo’s improvements to the telescope and resulting astronomical observations supporting the Copernican heliocentric view.

Bad news for Galileo, they also brought him to the attention of the Roman Inquisition.

Biblical references such as, “The Lord set the Earth on its Foundations; it can Never be Moved.” (Psalm 104:5) and “And the Sun Rises and Sets and Returns to its Place.” (Ecclesiastes 1:5) were taken at the time as literal and immutable fact and formed the basis for religious objection to the heliocentric model.

Galileo was brought before inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani for trial. The astronomer backpedaled before the Inquisition, but only to a point, testifying in his fourth deposition on June 21, 1633: “I do not hold this opinion of Copernicus, and I have not held it after being ordered by injunction to abandon it. For the rest, here I am in your hands; do as you please”.

There is a story about Galileo, which may or may not be true. Refusing to accept criticism of his deeply held conviction the astronomer muttered “Eppur si muove” — “And yet it moves”.

The Inquisition condemned the astronomer to “abjure, curse, & detest” his Copernican heliocentric views, returning him to house arrest at his villa in 1634, there to spend the rest of his life. Galileo Galilei, the Italian polymath who all but orchestrated the transition from late middle ages to scientific Renaissance, died on January 8, 1642, desiring to be buried in the main body of the Basilica of Santa Croce, next to the tombs of his father and ancestors.

Galileo’s desires were ignored at the time but, 95 years later, Galileo was re-interred in the basilica, according to his wishes.

Often, atmospheric conditions in these burial vaults lead to natural mummification of a corpse. Sometimes, the dead look almost lifelike. When it came to saints, believers took this to be proof of the incorruptibility of these individuals and small body parts were taken, as holy relics.

Such a custom seems ghoulish today but the practice went back, to antiquity. Galileo is not now and never was a Saint of the Catholic church, quite the opposite. The Inquisition had judged the man to be an enemy of the church, a heretic.

Even so, the condition of Galileo’s body may have made him appear thus “incorruptible”. Be that as it may, one Anton Francesco Gori removed the thumb, index and middle fingers on March 12, 1737. The digits with which Galileo wrote down his theories of the cosmos. The digits with which he would have adjusted his telescope.

Two fingers and a tooth disappeared for a time, later purchased at auction and rejoining their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day these are the only human body parts in a museum otherwise devoted, to scientific instrumentation.

380 years after the man’s death Galileo’s extremity points upward toward the glory of the cosmos. It is the most famous middle finger on earth, flipping the bird in eternal defiance to those lesser specimens who once condemned a man for ideas ahead of his time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.