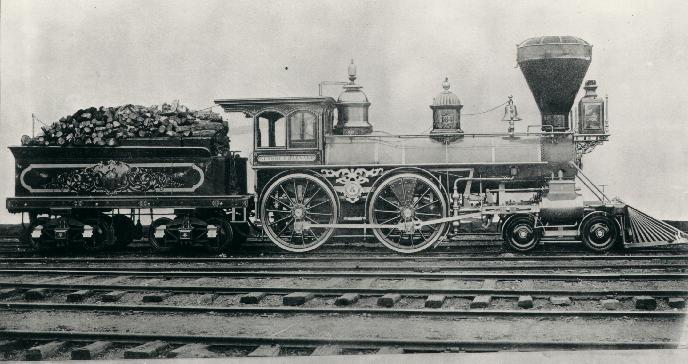

The wood burning steam locomotive #171 left Jersey City, New Jersey on July 15, 1864, pulling 17 passenger and freight cars. On board were 833 Confederate Prisoners of War and 128 Union guards, heading from Point Lookout, Maryland to the Federal prison camp in Elmira, New York.

Engine #171 was an “extra” that day, running behind a scheduled train numbered West #23. West #23 displayed warning flags, giving the second train right of way, but #171 was delayed while guards located missing prisoners. Then there was the wait for the drawbridge. By the time #171 reached Port Jervis, Pennsylvania, the train was four hours behind schedule.

Telegraph operator Douglas “Duff” Kent was on duty at the Lackawaxen Junction station, near Shohola Pennsylvania. Kent had seen West #23 pass through that morning with the “extra” flags. His job was to hold eastbound traffic at Lackawaxen until the second train passed.

He might have been drunk that day, but nobody’s sure. He disappeared the following day, never to be seen again.

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the All Clear at 2:45, the main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola.

Only four miles of track now lay between the two speeding locomotives.

The two trains met head-on at “King and Fuller’s Cut”, a section of track following a blind curve with only 50’ of visibility.

Engineer Samuel Hoit at the throttle of the coal train had time to jump clear, and survived the wreck. Many of the others, never had a chance.

Historian Joseph C. Boyd described what followed on the 100th anniversary of the wreck:

“[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken.” The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. [Witnesses] saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

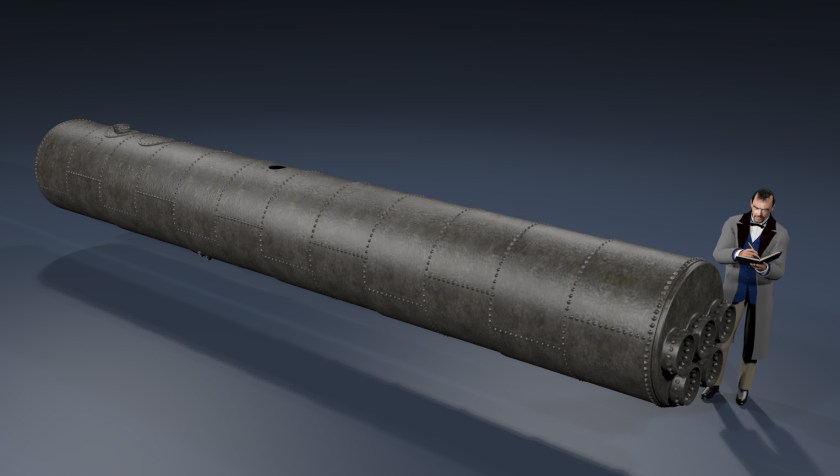

Pinned against the split boiler plate and slowly scalded to death, engineer William Ingram lived long enough to speak with would-be rescuers. “With his last breath he warned away all who went near to try and aid him, declaring that there was danger of the boiler exploding and killing them.”

Frank Evans, a guard on the train, describes the scene: “The two locomotives were raised high in air, face to face against each other, like giants grappling. The tender of our locomotive stood erect on one end. The engineer and fireman, poor fellows, were buried beneath the wood it carried. Perched on the reared-up end of the tender, high above the wreck, was one of our guards, sitting with his gun clutched in his hands, dead!. The front car of our train was jammed into a space of less than six feet. The two cars behind it were almost as badly wrecked. Several cars in the rear of those were also heaped together.”

51 Confederate prisoners and 17 Union guards were killed on the spot, or died within a day of the wreck. Five prisoners escaped in the confusion.

Captured at Spotsylvania early in 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry soldier James Tyner was a POW at this time, languishing in “Hellmira” – the fetid POW camp at Elmira, New York. “The Andersonville of the Northern Union.”

Captured at Spotsylvania early in 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry soldier James Tyner was a POW at this time, languishing in “Hellmira” – the fetid POW camp at Elmira, New York. “The Andersonville of the Northern Union.”

Tyner’s brother William was one of the prisoners on board #171.

William was badly injured in the wreck, surviving only long enough to avoid a mass grave alongside a train track, in Shohola. William Tyner was transported to Elmira where he died three days later, never regaining consciousness.

I’ve always wondered if the brothers were able to find one another, that one last time. James Tyner was my own twice-great Grandfather, one of four brothers who went to war for North Carolina, in 1861.

We’ll never know. James Tyner died in captivity on March 13, 1865, 27 days before General Lee’s surrender, at Appomattox. Of the four Tyner brothers, Nicholas alone survived the war. He laid down his arms on the order of the man they called “Marse Robert”, and walked home to pick up the shattered bits of his life, in the Sand Hills of North Carolina.

“About 56,000 soldiers died in prisons during the war, accounting for almost 10% of all Civil War fatalities. During a period of 14 months in Camp Sumter, located near Andersonville, Georgia, 13,000 (28%) of the 45,000 Union soldiers confined there died. At Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois, 10% of its Confederate prisoners died during one cold winter month; and Elmira Prison in New York state, with a death rate of 25%, very nearly equaled that of Andersonville”. H/T Wikipedia

Afterward

Burial details worked throughout the night of July 15 until dawn of the following day.

Two Confederate soldiers, the brothers John and Michael Johnson, died overnight and were buried in the congregational church yard across the Delaware river, in Barryville, New York.

The remaining POW dead and those about to die were buried alongside the track in a 75′ trench, placed four at a time in crude boxes fashioned from the wreckage. Conventional caskets arrived overnight. Individual graves were dug for the 17 Federal dead, and they too were laid alongside the track.

As the years went by, memorial markers faded and then disappeared, altogether. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they had passed.

The “pumpkin flood“ of 1903 scoured the rail line, uncovering many of the dead and carrying away their mortal remains. It must have been a sight – caskets moving with the flood, bobbing like so many fishing plugs, alongside countless numbers of that year’s pumpkin crop.

The “pumpkin flood“ of 1903 scoured the rail line, uncovering many of the dead and carrying away their mortal remains. It must have been a sight – caskets moving with the flood, bobbing like so many fishing plugs, alongside countless numbers of that year’s pumpkin crop.

On June 11, 1911, the forgotten dead of Shohola were disinterred, and reburied in mass graves in the Woodlawn national cemetery in Elmira, New York. Two brass plaques bear the names of the dead, mounted to opposite sides of a common stone marker.

The names of the Union dead, face north. Those of the Confederate side, face south. To my knowledge, this is the only instance from the Civil War era, in which Union and Confederate share a common grave.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

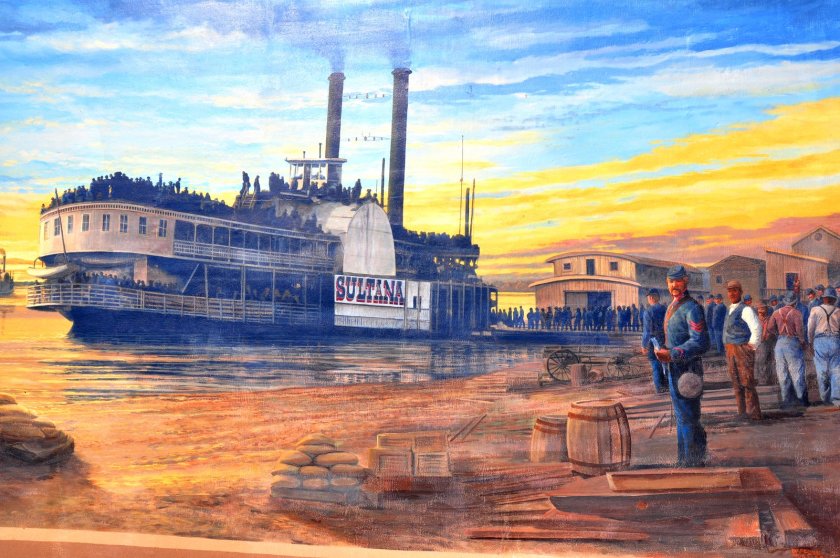

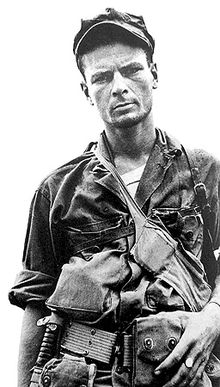

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows.

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows. The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence.

The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence. Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue

Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.”

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.” Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

After a year coaching at Providence College in 1939 and a year playing professional football for the Chicago Cardinals in 1940, Tonelli joined the Army in early 1941, assigned to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment in Manila.

After a year coaching at Providence College in 1939 and a year playing professional football for the Chicago Cardinals in 1940, Tonelli joined the Army in early 1941, assigned to the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment in Manila. Military forces of Imperial Japan appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as US military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines.

Military forces of Imperial Japan appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as US military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines. On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat the marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks swerved out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.

On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat the marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks swerved out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March. Minutes later, a Japanese officer appeared, speaking perfect English. “Did one of my men take something from you?” “Yes”, Tonelli replied. “My school ring”. “Here,” said the officer, pressing the ring into his hand. “Hide it somewhere. You may not get it back next time”. Tonelli was speechless. “I was educated in America”, the officer said. “At the University of Southern California. I know a little about the famous Notre Dame football team. In fact, I watched you beat USC in 1937. I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you”.

Minutes later, a Japanese officer appeared, speaking perfect English. “Did one of my men take something from you?” “Yes”, Tonelli replied. “My school ring”. “Here,” said the officer, pressing the ring into his hand. “Hide it somewhere. You may not get it back next time”. Tonelli was speechless. “I was educated in America”, the officer said. “At the University of Southern California. I know a little about the famous Notre Dame football team. In fact, I watched you beat USC in 1937. I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you”. The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others. Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors.

Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors. On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

Military force had to be called out in 1975, to dispel crowds at a religious school in Qom. Khomeini declared it the beginning of “Freedom and liberation from the bonds of imperialism”. By this time Khomeini was too hot to handle even for the Iraqis, and he moved to Paris. It was only a few short months before his triumphant return.

Military force had to be called out in 1975, to dispel crowds at a religious school in Qom. Khomeini declared it the beginning of “Freedom and liberation from the bonds of imperialism”. By this time Khomeini was too hot to handle even for the Iraqis, and he moved to Paris. It was only a few short months before his triumphant return. Khomeini re-entered Iran in February, as the Shah went from country to country, looking for a place to stay. With the now-former King of Kings suffering from a form of non-Hodgkins Lymphoma, President Jimmy Carter reluctantly allowed the Shah into the US for surgery. Pahlavi left on December 15, 1979 for Panama.

Khomeini re-entered Iran in February, as the Shah went from country to country, looking for a place to stay. With the now-former King of Kings suffering from a form of non-Hodgkins Lymphoma, President Jimmy Carter reluctantly allowed the Shah into the US for surgery. Pahlavi left on December 15, 1979 for Panama. Meanwhile, now “Grand Ayatollah” Khomeini was denouncing what he saw as an American plot. Revolutionaries stormed the American embassy and seized 66 hostages. 13 women and black Americans were released. Richard Queen, a white man sick with Multiple Sclerosis, was released nine months later. The remaining 52 hostages would be 444 days in captivity, paraded before television cameras in blindfolds as Khomeini denounced “The Great Satan”.

Meanwhile, now “Grand Ayatollah” Khomeini was denouncing what he saw as an American plot. Revolutionaries stormed the American embassy and seized 66 hostages. 13 women and black Americans were released. Richard Queen, a white man sick with Multiple Sclerosis, was released nine months later. The remaining 52 hostages would be 444 days in captivity, paraded before television cameras in blindfolds as Khomeini denounced “The Great Satan”. Aside from some of the most dismal economic conditions in American history, the Iranian hostage crisis did more than anything else to doom Jimmy Carter, to a single term.

Aside from some of the most dismal economic conditions in American history, the Iranian hostage crisis did more than anything else to doom Jimmy Carter, to a single term.

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904.

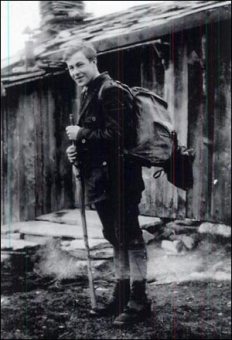

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904. The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains.

The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains. Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

You must be logged in to post a comment.