In the five years I’ve been writing “Today in History”, I’ve written about 450 of these stories. A father isn’t supposed to have favorites among his “children”, but I have to confess. I do. This is not one of those. This one, I detest.

The Oxford on-line Dictionary defines vivisection as: “noun – the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of experimentation or scientific research”.

During the reign of Queen Victoria, British monarch from June 20, 1837 to January 22, 1901, a powerful opposition arose in Great Britain to the dissection of live animals. Labeled as “vivisection” by opponents of the practice, experiments were often performed in front of audiences of medical students, with or without anesthesia.

The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876 stipulated that subject animals must be anesthetized, unless anesthesia would interfere with the point of the experiment. The measure further required that each animal could only be used once, though multiple procedures were permitted so long as each was part of the same experiment.

In the end, the subject animal had to be killed when the study was over.

In 1902, about the time when Russian physiologist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was doing his conditioning experiments om dogs, Ernest Starling performed his first “experiment” on a small brown terrier. Whether a stray or someone’s pet, is unclear. A further “demonstration” was performed on the same animal by William Bayliss on February 2, 1903, at the end of which the dog was killed with a knife to the heart.

I don’t care to linger on the details of what was done to this dog. It was difficult enough, to read about it. Suffice it to say that Bayliss and Starling’s classes were infiltrated by two Swedish anti-vivisection activists, Lizzy Lind and Leisa Katherine Schartau.

The two women had attended 50 such classes at University College, keeping a diary throughout and later publishing observations in “The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology”. In it, the pair disputed that the brown dog had been anesthetized, reporting that “The dog struggled forcibly during the whole experiment and seemed to suffer extremely during the stimulation. No anesthetic had been administered in my presence, and the lecturer said nothing about any attempts to anesthetize the animal having previously been made”.

Stephen Coleridge, secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society heard the two women’s story, and spoke angrily on behalf of the terrier. “If this is not torture”, the barrister asked, “let Mr. Bayliss and his friends … tell us in Heaven’s name what torture is“.

There was little doubt that either professor if not both, would sue for libel. Bayliss did and the jury retired for 25 minutes, returning with a unanimous verdict. Bayliss was awarded £2,000 with £3,000 in court costs, equivalent to about £250,000 today, the verdict read to the applause of physicians in the public gallery.

On September 15, 1906, the World League against Vivisection unveiled a statue in Battersea’s Latchmere Recreation Ground, bearing the inscription “In Memory of the Brown Terrier Dog Done to Death in the Laboratories of University College in February 1903 after having endured Vivisection extending over more than Two Months and having been handed over from one Vivisector to Another Till Death came to his Release. Also in Memory of the 232 dogs Vivisected at the same place during the year 1902. Men and Women of England how long shall these Things be?”

Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw and Anglo-Irish suffragist Charlotte Despard spoke at the event, but medical students were outraged.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands.

Riots ensued, the worst nights occurring in London on December 10, 1907, when 1,000 medical students tried to pull the statue down, battling over the memorial with suffragettes, trade unionists and over 400 police officers.

More riots and brawls broke out in the weeks that followed. Before long, the authorities were looking for a quiet way to make the statue go away. Four workmen and 120 police officers quietly removed the Brown Dog Memorial over the night of March 9-10, 1910, hiding it in a bicycle shed. 3,000 anti-vivisectionists gathered in Trafalgar Square to demand its return, but to no avail. The statue never reappeared, later to be broken up and melted down.

Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

For all the fuss, it hardly made a difference. There were something like 300 experiments on live animals, in the year 1875. By the time of the brown terrier’s live dissection, the number was 19,084. In 2005 the figure had increased to 2.81 million, and that’s just the vertebrates. 7,306 of those, were dogs.

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier.

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier. He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France.

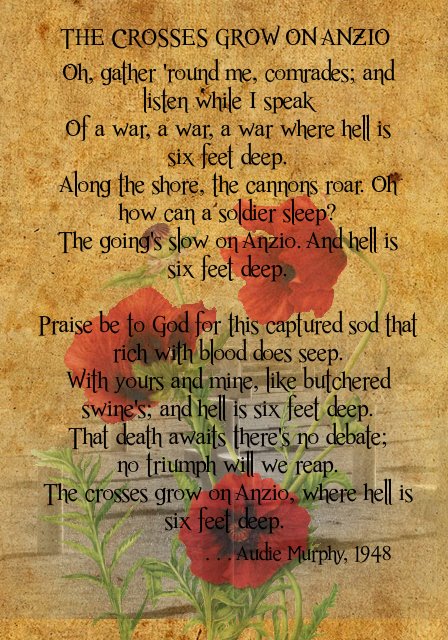

He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France. “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

“Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

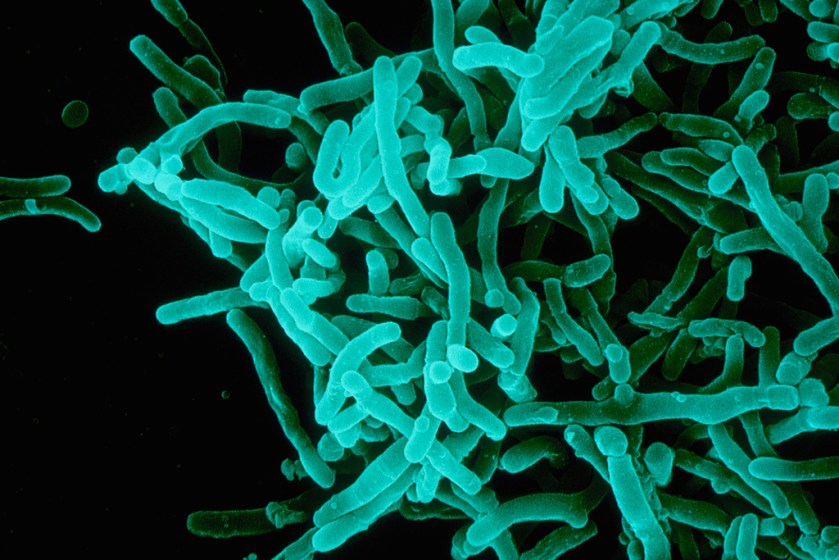

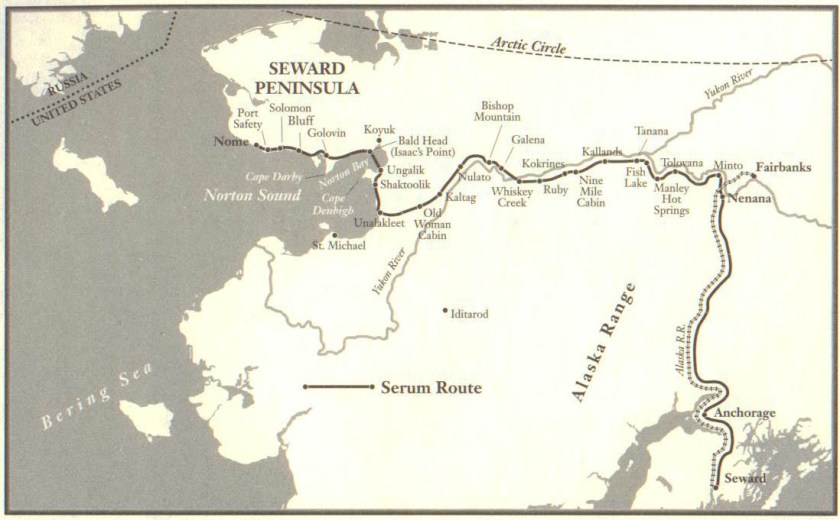

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

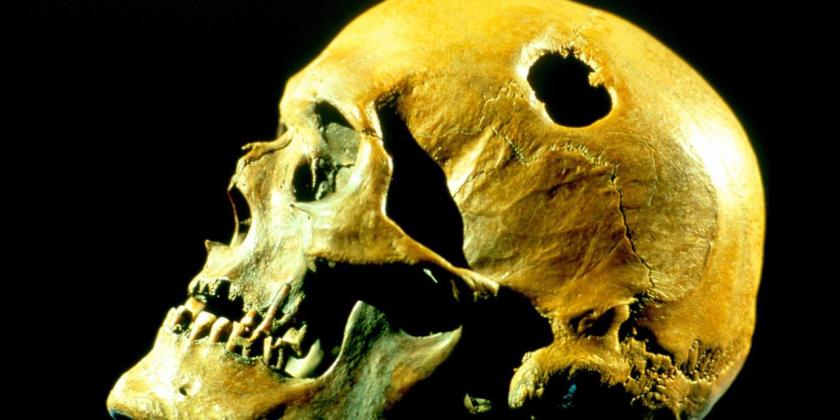

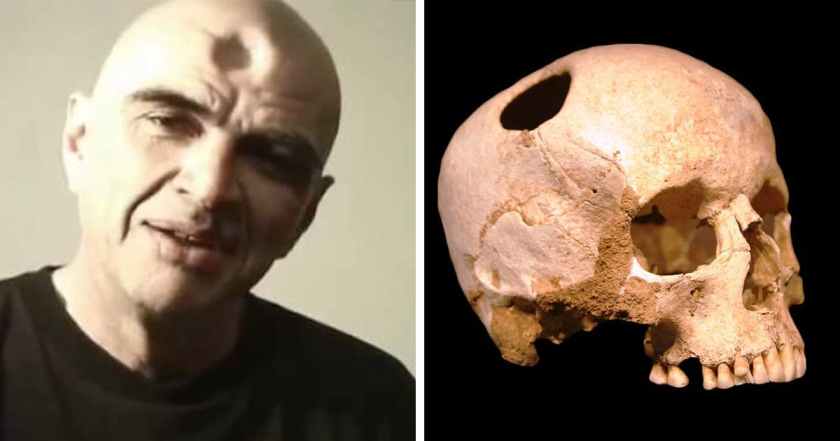

To prove the value of his ‘third eye’ theory, to his own satisfaction if to no one else, Hughes drilled a hole in his own skull in 1965, using a Black & Decker electric drill. He must have thought it proved the point, because he expanded on his theory with “Trepanation: A Cure for Psychosis”, followed by an autobiography, “The Book with the Hole”, published in 1972.

To prove the value of his ‘third eye’ theory, to his own satisfaction if to no one else, Hughes drilled a hole in his own skull in 1965, using a Black & Decker electric drill. He must have thought it proved the point, because he expanded on his theory with “Trepanation: A Cure for Psychosis”, followed by an autobiography, “The Book with the Hole”, published in 1972. At age 27, Amanda Feilding brought an electric dentist’s drill to her London apartment, and drilled a hole in her skull. After four unsuccessful years trying to find a surgeon to do it for her, “I thought, ‘Well, I’m a sculptor, I may as well do it myself'”.

At age 27, Amanda Feilding brought an electric dentist’s drill to her London apartment, and drilled a hole in her skull. After four unsuccessful years trying to find a surgeon to do it for her, “I thought, ‘Well, I’m a sculptor, I may as well do it myself'”. At the time, the Iron County DA also considered charges against ABC News reporter Chris Cuomo, for aiding in the crime.

At the time, the Iron County DA also considered charges against ABC News reporter Chris Cuomo, for aiding in the crime.

There are roughly a quadrillion such synapses, meaning that any given thought could wend its way through more pathways than there are molecules in the known universe. This is roughly the case, whether you are Stephen J. Hawking, or Forrest Gump.

There are roughly a quadrillion such synapses, meaning that any given thought could wend its way through more pathways than there are molecules in the known universe. This is roughly the case, whether you are Stephen J. Hawking, or Forrest Gump. The Alcor Life Extension Foundation, the self-described “world leader in cryonics, cryonics research, and cryonics technology” explains “Cryonics is an effort to save lives by using temperatures so cold that a person beyond help by today’s medicine can be preserved for decades or centuries until a future medical technology can restore that person to full health”.

The Alcor Life Extension Foundation, the self-described “world leader in cryonics, cryonics research, and cryonics technology” explains “Cryonics is an effort to save lives by using temperatures so cold that a person beyond help by today’s medicine can be preserved for decades or centuries until a future medical technology can restore that person to full health”.

In 1988, television writer Dick Clair, best known for television sitcoms “It’s a Living”, “The Facts of Life”, and “Mama’s Family”, was dying of AIDS related complications. In his successful suit against the state of California, “Roe v. Mitchell” (Dick Clair was John Roe), Judge Aurelio Munoz “upheld the constitutional right to be cryonically suspended”, winning the “right” for everyone in California.

In 1988, television writer Dick Clair, best known for television sitcoms “It’s a Living”, “The Facts of Life”, and “Mama’s Family”, was dying of AIDS related complications. In his successful suit against the state of California, “Roe v. Mitchell” (Dick Clair was John Roe), Judge Aurelio Munoz “upheld the constitutional right to be cryonically suspended”, winning the “right” for everyone in California. The court battle produced a “family pact” written on a cocktail napkin, which was ruled authentic and allowed into evidence. So it is that Ted Williams’ head went into cryonic preservation in one container, his body in another.

The court battle produced a “family pact” written on a cocktail napkin, which was ruled authentic and allowed into evidence. So it is that Ted Williams’ head went into cryonic preservation in one container, his body in another. In April 1773, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to Jacques Dubourg. “I wish it were possible”, Franklin wrote, “to invent a method of embalming drowned persons, in such a manner that they might be recalled to life at any period, however distant; for having a very ardent desire to see and observe the state of America a hundred years hence, I should prefer to an ordinary death, being immersed with a few friends in a cask of Madeira, until that time, then to be recalled to life by the solar warmth of my dear country! But…in all probability, we live in a century too little advanced, and too near the infancy of science, to see such an art brought in our time to its perfection”.

In April 1773, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to Jacques Dubourg. “I wish it were possible”, Franklin wrote, “to invent a method of embalming drowned persons, in such a manner that they might be recalled to life at any period, however distant; for having a very ardent desire to see and observe the state of America a hundred years hence, I should prefer to an ordinary death, being immersed with a few friends in a cask of Madeira, until that time, then to be recalled to life by the solar warmth of my dear country! But…in all probability, we live in a century too little advanced, and too near the infancy of science, to see such an art brought in our time to its perfection”.

Others believe such outbreaks to be evidence of Sydenham’s chorea, a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet and closely associated with a medical history of Rheumatic fever. Particularly in children.

Others believe such outbreaks to be evidence of Sydenham’s chorea, a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet and closely associated with a medical history of Rheumatic fever. Particularly in children.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

couple kept their kids focused on school.

couple kept their kids focused on school.

do to protect the family. I grew up in this era. Each summer, polio would come like The Plague. Beaches and pools would close — because of the fear that the poliovirus was waterborne. Children had to stay away from crowds, so they often were banned from movie theaters, bowling alleys, and the like. My mother gave us all a ‘polio test’ each day: Could we touch our toes and put our chins to our chest? Every stomach ache or stiffness caused a panic. Was it polio? I remember the awful photos of children on crutches, in wheelchairs and iron lungs. And coming back to school in September to see the empty desks where the children hadn’t returned.”

do to protect the family. I grew up in this era. Each summer, polio would come like The Plague. Beaches and pools would close — because of the fear that the poliovirus was waterborne. Children had to stay away from crowds, so they often were banned from movie theaters, bowling alleys, and the like. My mother gave us all a ‘polio test’ each day: Could we touch our toes and put our chins to our chest? Every stomach ache or stiffness caused a panic. Was it polio? I remember the awful photos of children on crutches, in wheelchairs and iron lungs. And coming back to school in September to see the empty desks where the children hadn’t returned.”

On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms.

On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms. within hours of the first symptoms. There’s a story about four young, healthy women playing bridge well into the night. By morning, three were dead of influenza.

within hours of the first symptoms. There’s a story about four young, healthy women playing bridge well into the night. By morning, three were dead of influenza. Around the planet, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people. A third of the population of the entire world, at that time. Estimates run as high 50 to 100 million killed. For purposes of comparison, the “Black Death” of 1347-51 killed 20 million Europeans.

Around the planet, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people. A third of the population of the entire world, at that time. Estimates run as high 50 to 100 million killed. For purposes of comparison, the “Black Death” of 1347-51 killed 20 million Europeans.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired. The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.