Morris Frank lost the use of an eye in a childhood accident, losing his vision altogether when a boxing accident damaged the other when he was 16. Frank hired a boy to guide him around, but the young man was easily bored and sometimes wandered off leaving Frank to fend for himself.

German specialists had been working at this time, on the use of Alsatians (German Shepherds), to act as guide dogs for WWI veterans blinded by mustard gas. An American breeder living in Switzerland, Dorothy Harrison Eustis, wrote an article about the work in a 1927 issue of the Saturday Evening Post. When Frank’s father read him the article, he wrote to Eustis pleading with her to train a dog for himself. “Is what you say really true? If so, I want one of those dogs! And I am not alone. Thousands of blind like me abhor being dependent on others. Help me and I will help them. Train me and I will bring back my dog and show people here how a blind man can be absolutely on his own. We can then set up an instruction center in this country to give all those here who want it a chance at a new life.”

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Man and dog stepped off the ship in 1928 to a throng of reporters. There were flash bulbs, shouted questions and the din of traffic and honking horns that can only be New York City. Buddy never wavered. At the end of that first day, Dorothy Eustis received a single word telegram: “Success”. Morris Frank was set on the path that would become his life’s mission: to get Seeing Eye Dogs accepted all over the country.

Frank and Eustis established the first guide dog training school in the US in Nashville, on January 29, 1929. Frank was true to his word, becoming a tireless advocate of public accessibility for the blind and their guide dogs. In 1928, he was routinely told that Buddy couldn’t ride in the passenger compartment with him. Seven years later, all railroads in the United States had adopted policies allowing guide dogs to remain with their owners while onboard. By 1956, every state in the Union had passed laws guaranteeing access to public spaces for blind people and their dogs.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

Buddy’s health was failing in the end, but the team had one more hurdle to cross. One more barrier to break. Frank wanted to fly in a commercial airplane with his guide dog. The pair did so on this day in 1938, flying from Chicago to Newark, Buddy curled up at Morris Frank’s feet. United Air Lines was the first to adopt the policy, granting “all Seeing Eye dogs the privilege of riding with their masters in the cabins of any of our regularly scheduled planes.”

Buddy was all business during the day, but, to the end of her life, she liked to end her work day with a roll on the floor with Mr. Frank. Buddy died seven days after that plane trip, but she had made her mark. By this time there were 250 seeing eye dogs working across the country, and their number was growing fast. Buddy’s replacement was also called Buddy, as was every seeing eye dog Frank would ever own, until he passed in 1980.

It’s estimated today that there are over 10,000 seeing eye dogs, currently working in the United States.

The world’s most famous dog show was first held on May 8, 1877, and called the “First Annual NY Bench Show.” The venue was Gilmore’s Garden at the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, a hall which would later be known as Madison Square Garden. Interestingly, another popular Gilmore Garden event of the era was boxing. Competitive boxing was illegal in New York in those days, so events were billed as “exhibitions” or “illustrated lectures.” I love that last one.

The world’s most famous dog show was first held on May 8, 1877, and called the “First Annual NY Bench Show.” The venue was Gilmore’s Garden at the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, a hall which would later be known as Madison Square Garden. Interestingly, another popular Gilmore Garden event of the era was boxing. Competitive boxing was illegal in New York in those days, so events were billed as “exhibitions” or “illustrated lectures.” I love that last one. 1,200 dogs arrived for that first show, in an event so popular that the originally planned three days morphed into four. The Westminster Kennel Club donated all proceeds from the fourth day to the ASPCA, for the creation of a home for stray and disabled dogs. The organization remains supportive of animal charities, to this day.

1,200 dogs arrived for that first show, in an event so popular that the originally planned three days morphed into four. The Westminster Kennel Club donated all proceeds from the fourth day to the ASPCA, for the creation of a home for stray and disabled dogs. The organization remains supportive of animal charities, to this day. one in 1946. Even so, “Best in Show” was awarded fifteen minutes earlier than it had been, the year before. I wonder how many puppies were named “Tug” that year. The Westminster dog show was first televised in 1948, three years before the first nationally televised college football game.

one in 1946. Even so, “Best in Show” was awarded fifteen minutes earlier than it had been, the year before. I wonder how many puppies were named “Tug” that year. The Westminster dog show was first televised in 1948, three years before the first nationally televised college football game.

Since the late 60s, the Westminster Best in Show winner has celebrated at Sardi’s, a popular mid-town eatery in the theater district and birthplace of the Tony award. And then the Nanny State descended, pronouncing that 2012 would be their last. There shalt be no dogs dining any restaurants, not while Mayor Bloomberg is around.

Since the late 60s, the Westminster Best in Show winner has celebrated at Sardi’s, a popular mid-town eatery in the theater district and birthplace of the Tony award. And then the Nanny State descended, pronouncing that 2012 would be their last. There shalt be no dogs dining any restaurants, not while Mayor Bloomberg is around.

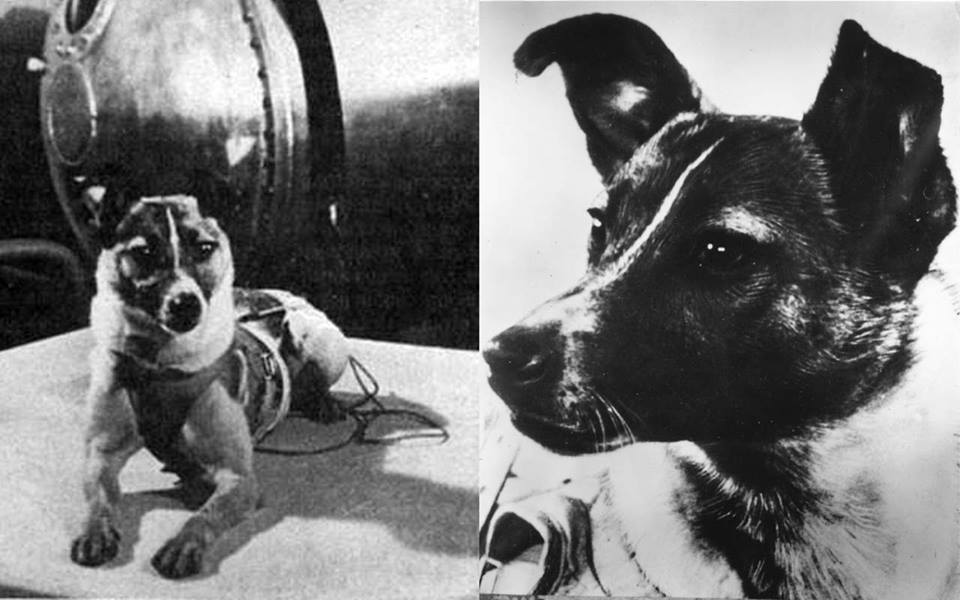

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”.

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”. In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

By the last year of WW1, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, the Germans 30,000. General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces recommended the use of dogs as sentries, messengers and draft animals in the spring of 1918. However, with the exception of a few sled dogs in Alaska, the US was the only country to take part in World War I with virtually no service dogs in its military.

By the last year of WW1, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, the Germans 30,000. General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces recommended the use of dogs as sentries, messengers and draft animals in the spring of 1918. However, with the exception of a few sled dogs in Alaska, the US was the only country to take part in World War I with virtually no service dogs in its military.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

dogs of King Alyattes of Lydia killed some of his Cimmerian adversaries and routed the rest around 600BC, permanently driving the invader from Asia Minor in the earliest known use of war dogs in battle.

dogs of King Alyattes of Lydia killed some of his Cimmerian adversaries and routed the rest around 600BC, permanently driving the invader from Asia Minor in the earliest known use of war dogs in battle.

The most famous MWD of WWII was “Chips”, a German Shepherd assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division in Italy. Trained as a sentry dog, Chips broke away from his handler and attacked an enemy machine gun nest. Wounded in the process, his singed fur demonstrated the point-blank fire with which the enemy fought back. To no avail. Chips single-handedly forced the surrender of the entire gun crew.

The most famous MWD of WWII was “Chips”, a German Shepherd assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division in Italy. Trained as a sentry dog, Chips broke away from his handler and attacked an enemy machine gun nest. Wounded in the process, his singed fur demonstrated the point-blank fire with which the enemy fought back. To no avail. Chips single-handedly forced the surrender of the entire gun crew.

At 256 tons with a barrel of 111′ 7″, the “Paris Gun” hurled 38″ shells into the city from a range of 75 miles. If you were in Paris in 1918, you may never have heard of the German “super gun”. You’d have been well acquainted with the damage it caused. You never knew you were under attack until the explosion. The lucky ones were those who lived to see the 4’ deep, 10’-12’ wide crater.

At 256 tons with a barrel of 111′ 7″, the “Paris Gun” hurled 38″ shells into the city from a range of 75 miles. If you were in Paris in 1918, you may never have heard of the German “super gun”. You’d have been well acquainted with the damage it caused. You never knew you were under attack until the explosion. The lucky ones were those who lived to see the 4’ deep, 10’-12’ wide crater.

These little yarn dolls had names. They were Nénette and Rintintin.

These little yarn dolls had names. They were Nénette and Rintintin.

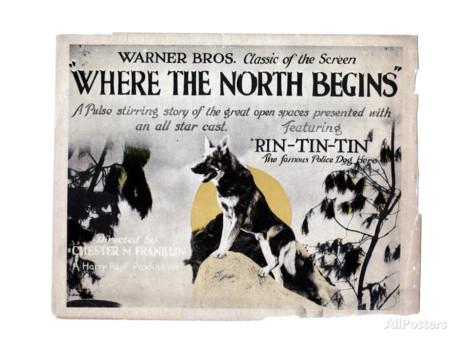

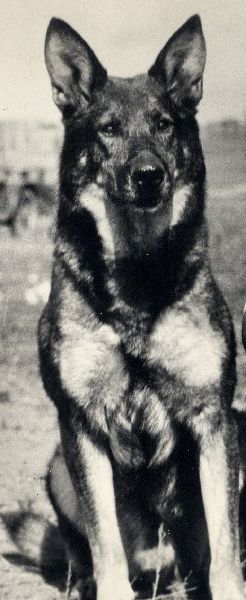

Walking the dog on “Poverty Row”, 1920s slang for B movie studios, did the trick. Rin Tin Tin got his first film break in 1922, replacing a camera shy wolf in “The Man from Hell’s River”. His first starring role in the 1923 “Where the North begins”, is credited with saving Warner Brothers Studios from bankruptcy.

Walking the dog on “Poverty Row”, 1920s slang for B movie studios, did the trick. Rin Tin Tin got his first film break in 1922, replacing a camera shy wolf in “The Man from Hell’s River”. His first starring role in the 1923 “Where the North begins”, is credited with saving Warner Brothers Studios from bankruptcy. Rin Tin Tin appeared in 27 feature length silent films, 4 “talkies”, and countless commercials and short films. Regular programming was interrupted to announce his passing on August 10, 1932, at the age of 13. An hour-long program about his life was broadcast the following day.

Rin Tin Tin appeared in 27 feature length silent films, 4 “talkies”, and countless commercials and short films. Regular programming was interrupted to announce his passing on August 10, 1932, at the age of 13. An hour-long program about his life was broadcast the following day. bloodlines. Rin Tin Tin and Nanette II produced at least 48 puppies. Duncan may have been obsessive about it, at least according to Mrs. Duncan. When she filed for divorce, she named Rin Tin Tin as co-respondent.

bloodlines. Rin Tin Tin and Nanette II produced at least 48 puppies. Duncan may have been obsessive about it, at least according to Mrs. Duncan. When she filed for divorce, she named Rin Tin Tin as co-respondent.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired. The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

States Marine Corps in 2006. The dog’s second deployment began in November, when he was paired with Marine Corporal Dustin J. Lee, stationed in the military police department at Marine Corps Logistics Base (MCLB), “Albany”.

States Marine Corps in 2006. The dog’s second deployment began in November, when he was paired with Marine Corporal Dustin J. Lee, stationed in the military police department at Marine Corps Logistics Base (MCLB), “Albany”. The most dreadful moment in the life of any parent, is when they receive word of the death of a child. It wasn’t long after Jerome and Rachel Lee were so notified, that they began efforts to adopt Lex. Dustin was gone, but they wanted to make his partner a permanent part of their family.

The most dreadful moment in the life of any parent, is when they receive word of the death of a child. It wasn’t long after Jerome and Rachel Lee were so notified, that they began efforts to adopt Lex. Dustin was gone, but they wanted to make his partner a permanent part of their family. In telling this story, I wish in some small way to honor my son in law Nate and daughter Carolyn, who together experienced Nate’s deployment as a Tactical Explosives Detection Dog handler with the US Army 3rd Infantry Division in Soltan Kheyl, Wardak Province, Afghanistan. Months after departing “The Ghan” in 2013, the couple was reunited with Nate’s “Battle Buddy”, MWD Zino, who is now retired and lives with them in Savannah. “Here & Now”, broadcast out of ‘Boston’s NPR News Station’ WBUR, did a great story on the reunion. You can hear the radio broadcast

In telling this story, I wish in some small way to honor my son in law Nate and daughter Carolyn, who together experienced Nate’s deployment as a Tactical Explosives Detection Dog handler with the US Army 3rd Infantry Division in Soltan Kheyl, Wardak Province, Afghanistan. Months after departing “The Ghan” in 2013, the couple was reunited with Nate’s “Battle Buddy”, MWD Zino, who is now retired and lives with them in Savannah. “Here & Now”, broadcast out of ‘Boston’s NPR News Station’ WBUR, did a great story on the reunion. You can hear the radio broadcast

life of his handler, and preventing further destruction of life and property. MWD Nemo was given the best of veterinary care and, on June 23 1967, USAF Headquarters directed that he be returned to the United States, the first sentry dog officially retired from active service. The C124 Globemaster touched down at Kelly Air Force Base, Texas, on July 22, 1967. Nemo lived out the seven years remaining to him in a permanent retirement kennel at the DoD Dog Center at Lackland Air Force Base.

life of his handler, and preventing further destruction of life and property. MWD Nemo was given the best of veterinary care and, on June 23 1967, USAF Headquarters directed that he be returned to the United States, the first sentry dog officially retired from active service. The C124 Globemaster touched down at Kelly Air Force Base, Texas, on July 22, 1967. Nemo lived out the seven years remaining to him in a permanent retirement kennel at the DoD Dog Center at Lackland Air Force Base.

You must be logged in to post a comment.