For thousands of years, bells have rung out to announce religious and civic occasions, weddings, funerals and other public announcements. The rich tones of a well-cast bell is capable of carrying for miles. Great Britain has so many bells, the place has been called the “Ringing Isle”.

The first bell in the city of Philadelphia would ring out to alert citizens of civic events and proclamations, and to the occasional public danger. Originally hung from a tree near the Pennsylvania State House, (now known as Independence Hall), that first bell dates back as far as the city itself, around 1682.

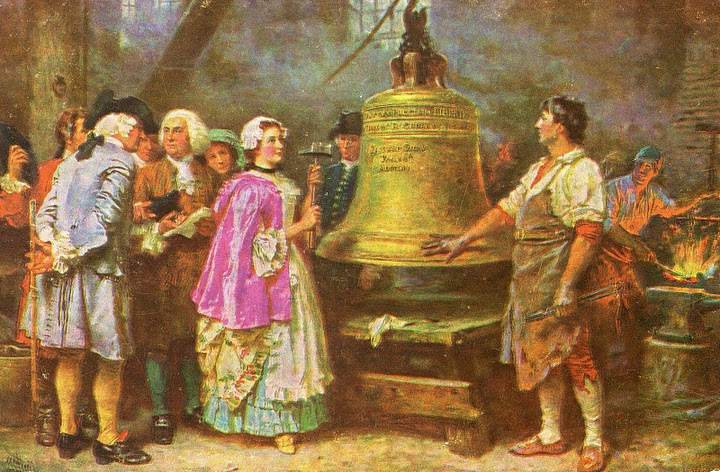

The “Liberty Bell” was ordered from the London bell foundry of Lester and Pack in 1752, (today the Whitechapel Bell Foundry), though that name wouldn’t come around until much later. Weighing in at 2,080 lbs, the bell arrived in August of that year. Written upon it was a passage from the Book of Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible; the third of five books of the Torah. “Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof”.

Mounted to a stand to test the sound, the first strike of the clapper cracked the bell’s rim. Authorities attempted to return it, but the ship’s master couldn’t take it on board. The bell was broken into pieces, melted down and re-cast by two local workmen, John Pass and John Stow.

The recast bell used 10% copper, making the metal less brittle. Pass and Snow bragged that the bell’s lettering was clearer on this second casting than the original. The newly re-cast bell was ready in March 1753, when City officials scheduled a public celebration to test the sound. There was free food and drink all around, but the crowd gasped and started to laugh when the bell was struck. It didn’t break this time, it was worse. Somebody said the thing sounded like two coal scuttles, banging together.

Humiliated, Pass and Stow hurriedly took the bell away, and once again broke it into pieces, and melted it down.

The whole performance was repeated, three months later. This time, most thought the sound to be satisfactory, and the bell was hung in the steeple of the State House. One who did not like the sound was Isaac Norris, speaker of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. Norris ordered a second bell in 1754 and attempted to return the old one for credit, but his efforts proved unsuccessful.

The new bell was attached to the tower clock, while the old one was, by vote of the Assembly, devoted “to such Uses as this House may hereafter appoint.” One of the earliest documented uses of the old bell comes to us in a letter from Benjamin Franklin to Catherine Ray, dated October 16, 1755: “Adieu. The Bell rings, and I must go among the Grave ones, and talk Politiks.”

Legends have grown around the bell, ringing in the public reading of the Declaration of independence on July 4, 1776. The story is a myth. There was no such reading on that day. The 2nd Continental Congress’ Declaration was announced to the public four days later on July 8, to a great ringing of bells. Whether the old bell itself rang on this day, remains uncertain. John C. Paige, author of an historical study of the bell for the National

Park Service, wrote “We do not know whether or not the steeple was still strong enough to permit the State House bell to ring on this day. If it could possibly be rung, we can assume it was. Whether or not it did, it has come to symbolize all of the bells throughout the United States which proclaimed Independence.”

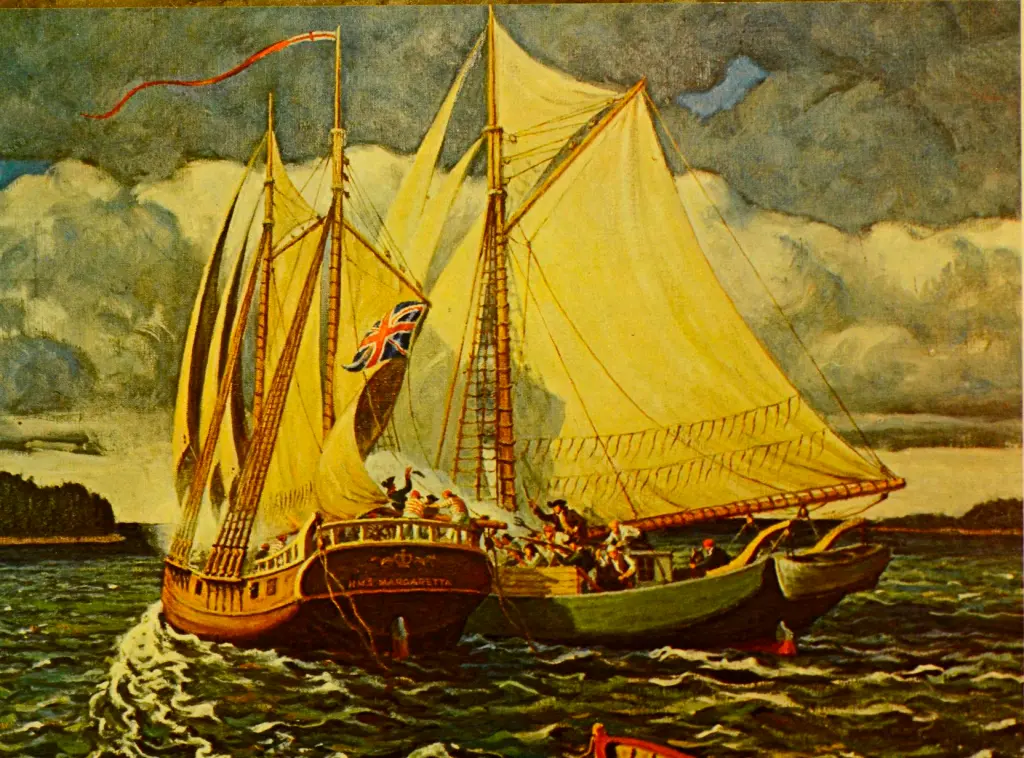

Bells are easily melted down and recast as bullets, and the bell was removed for safekeeping before the British occupation of Philadelphia, in 1777. The distinctive large crack began to develop sometime in the early 19th century, around the time when abolitionist societies adopted the symbol and began calling it “The Liberty Bell”.

The Philadelphia Public Ledger reported the last clear note ever sounded by the Liberty Bell, in its February 26, 1846 edition:

“The old Independence Bell rang its last clear note on Monday last in honor of the birthday of Washington and now hangs in the great city steeple irreparably cracked and dumb. It had been cracked before but was set in order of that day by having the edges of the fracture filed so as not to vibrate against each other … It gave out clear notes and loud, and appeared to be in excellent condition until noon, when it received a sort of compound fracture in a zig-zag direction through one of its sides which put it completely out of tune and left it a mere wreck of what it was.”

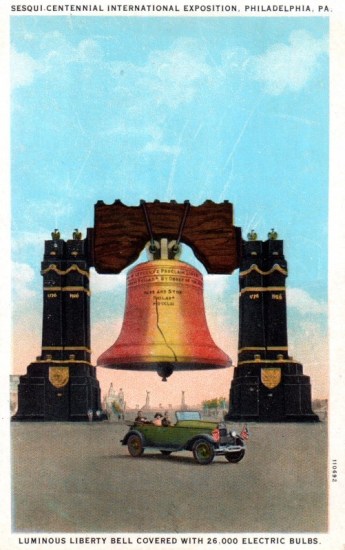

The bell would periodically travel to expositions and celebrations, but souvenir hunters would break off pieces from the rim. Additional cracking developed after several of these trips, and the bell’s travels were sharply curtailed after its return from Chicago, in 1893.

With the 1915 World’s Fair about to open in San Francisco, there were discussions of sending the Liberty Bell to California. The bell had never been west of St. Louis at that time, and the Philadelphia establishment balked. Former Pennsylvania governor Samuel Pennypacker complained that “The Bell is injured every time it leaves…children have seen this sacred Metal at fairs associated with fat pigs and fancy furniture. They lose all the benefit of the associations that cling to Independence Hall, and the bell should, therefore, never be separated from [Philadelphia].”

With the California tour off for now, Philadelphia Mayor Rudolph Blankenburg offered the next best thing. Bell Telephone had just completed a new transcontinental line, 3,400 miles of wire suspended from 130,000 poles. Three hundred dignitaries gathered at Bell offices in Philadelphia and San Francisco on February 11, 1915. With Alexander Graham Bell himself listening in from his own private line in Washington DC, the Liberty bell was sounded at 5pm, with all of them listening in on candlestick phones.

The California trip gained fresh impetus following the May 7 sinking ofn the British liner Lusitania. A cross-country whistle stop tour was planned for the bell, using the “best cushioned” rail car, in history.

As the nation’s most prominent German-American, Mayor Blankenburg himself came along, delivering “loyalty lectures” to immigrant groups on the importance of devotion to their adopted home country. “It is important to prepare against a possible foe abroad“, he would say, “….Let us, therefore, abolish all distinctions that may lead to ill feeling and let us call ourselves, before the whole world, Americans, first, last and all the time.”

The Liberty Bell drew crowds beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. Fully one- quarter of the American population turned out to see the liberty bell, a generator rigged so the bell could be seen by day or night. In many cities, those on the train couldn’t see where the crowd ended.

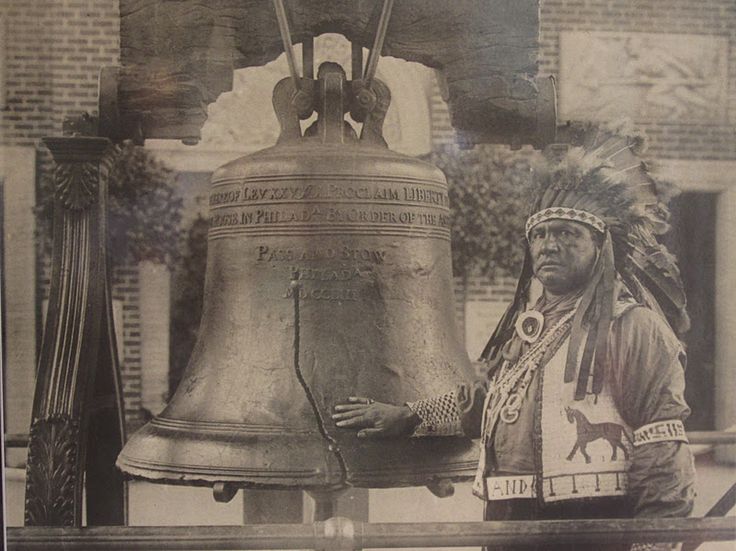

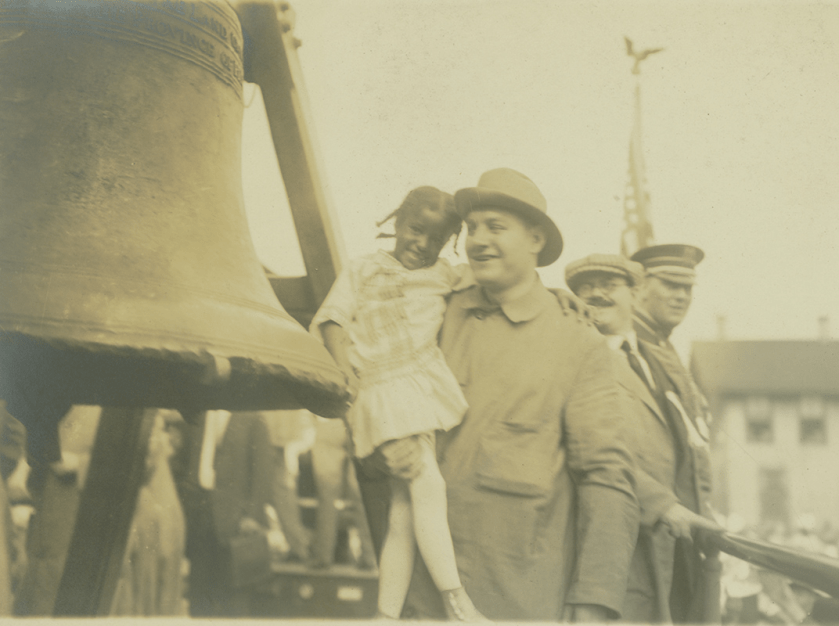

“Big Jim” Quirk, one of the police officers assigned to the train, recalled “In Kansas City, an old colored man who had been a slave came to touch it—he was 100 years old.” When the train pulled into another town, “an aged Mammie hobbled to the door of her cabin near the tracks, raised her hands and with her eyes streaming tears called out, ‘God Bless the Bell! God Bless the Dear Bell!’ It got to us somehow.”

In Denver, a group of blind girls were allowed to touch the Bell. One of them wanted to read the letters. You could have heard a pin drop, as a hushed crowd heard a small, sightless girl, pronounce these words: “Proclaim…Liberty…throughout…all…the…land.”

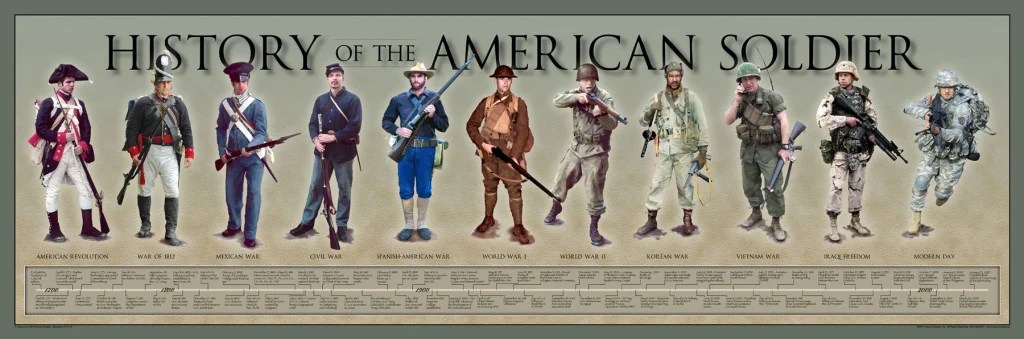

The Liberty Bell was enlisted once again in 1917 as the United States prepared to send her soldiers “over there” in the first democratically financed war, in history. Americans hurried to buy up war bonds, far exceeding the national goal of $2 Billion.

Today, two other bells join the Liberty Bell in the Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, PA. Weighing in at 13,000lbs, a half-ton for every original colony, the Centennial Bell was cast for America’s 100th birthday in 1876. To this day, this enormous bell rings once an hour, in the tower at Independence Hall.

In 1976, the people of Great Britain presented a gift to the people of the United States, in recognition of the friendship between the former adversaries. Weighing in at six tons and cast at the same foundry which produced the original bell, the “Bicentennial Bell” was dedicated by her Royal Highness, Queen Elizabeth, II, on July 6, 1976. On the side of the bell are inscribed these words:

FOR THE

PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES

FROM THE

PEOPLE OF BRITAIN

4 JULY 1976

LET FREEDOM RING

Back in 1893, the Liberty Bell passed through Indianapolis. Former President Benjamin Harrison may have had the last word on the subject, a sentiment fit to be inscribed on the old bell itself, below that verse from the Torah. “This old bell was made in England”, Harrison said, “but it had to be re-cast in America before it was attuned to proclaim the right of self-government and the equal rights of men.”

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own face. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own face. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

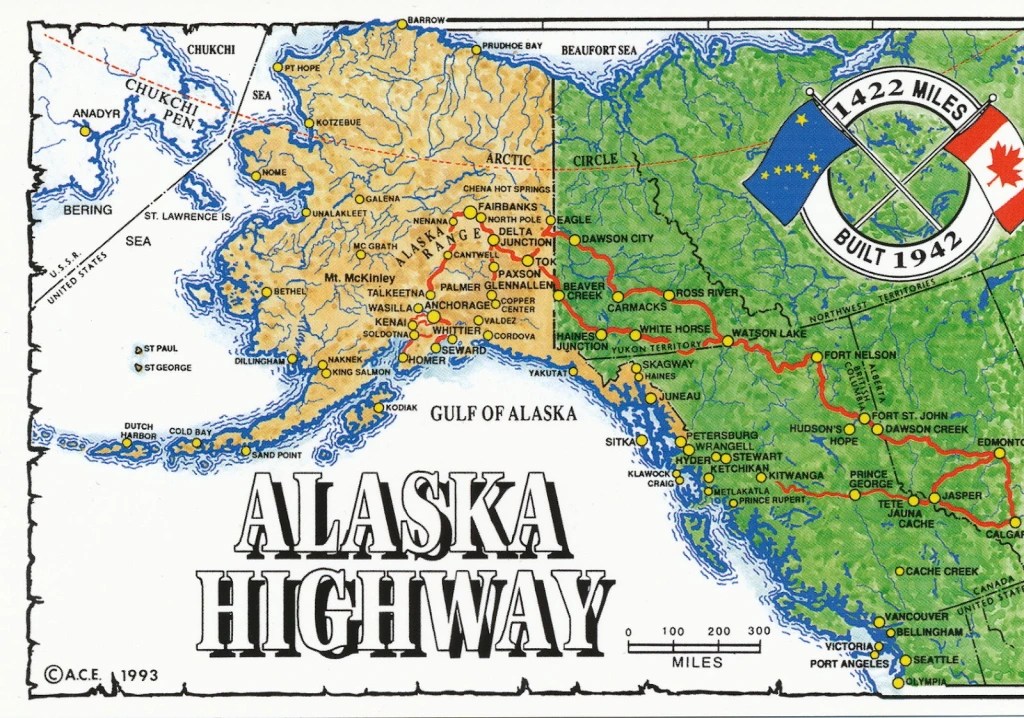

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.