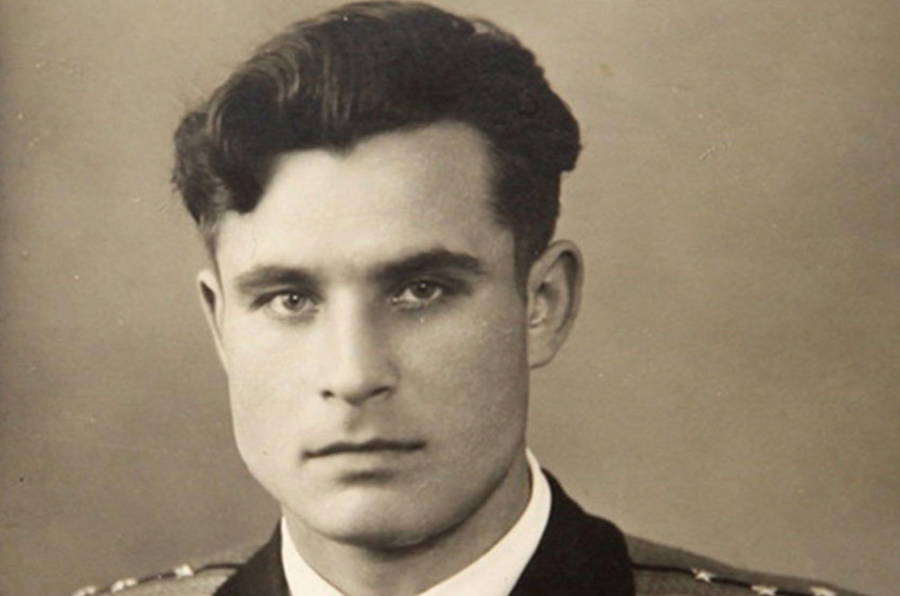

John William “Wild Bill” Crump was born in 1924 in the village of Opportunity, Washington. From the age of 5 he seemed destined for the air, his first flight with his father at the stick.

The world was at war in 1944, and badly in need of pilots. Wild Bill Crump arrived at Harding Field, Nebraska at the age of 20 to complete pilot training.

He came upon the most unlikely of co-pilots while earning his wings. Abandoned and alone, it was a two-week-old puppy. A young coyote in need of a home.

“Eugene the Jeep” came to public attention some eight years before that, part of the Popeye cartoon strip by E.C. Segar (rhymes with cigar).

Eugene was a dog-like of character with the magical power to go, just about anywhere.

In the early phase of World War II, military contractors labored to develop an off-road vehicle. It had to be capable of going anywhere, or close to it. Like Popeye’s sidekick Eugene, the General Purpose GP (“Jeep”) was just the thing. Eventually, the name stuck.

You see this coming, right? Crump named his new sidekick, “Jeep”.

Next came Baton Rouge. Training on the iconic P-47. The P-47 was a high-altitude fighter-bomber, the foremost ground attack aircraft of the American war effort in WW2.

P-47 cockpits were built for one, but regulations said nothing about a coyote.

So it was, there in Baton Rouge the pair learned to work together. When orders came for England, there was little question of what was next. The luxury liner RMS Queen Elizabeth was serving as a troop ship. No one would notice a little coyote pup smuggled on-board.

Next came RAF Martlesham Heath Airfield in Ipswich, England and the 360th fighter squadron, 359th fighter group.

Jeep became the unit mascot complete with his own “dog tags”, and vaccination records. He’d often entertain the airmen taking part in howling contests.

Curled up in the cockpit, Jeep came along on no fewer than five combat missions. One time, a series of sharp barks warned the pilot of incoming flak.

Wild Bill Crump survived the war, reenlisting in a time for the Berlin airlift. He later piloted for Bob Hope and the Les Brown Band, entertaining the troops in Berlin. Sadly, his co-pilot and battle buddy did not. On October 28,1944, a group of children brought the animal to school. Left tied to a tree he slipped his bonds, attempting to return home. It was raining at the time. Visibility was poor. Jeep was hit and killed by a military vehicle while returning to base.

Crump went on to fly 77 missions aboard the P51 Mustang “Jackie,” named after his high school sweetheart. The fuselage bore the image of a coyote in honor of his late co-pilot.

Jeep was buried with full military honors. A plaque marks his grave on the grounds of Playford Hall, an Elizabethan mansion dating back to 1590 and located in Ipswich, England.

As long as men have made war, animals have come along. And not just working animals. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that, when Norsemen went a’ Viking, they did so in the company of house cats. The idea may be amusing, but why not? Men at sea need food, and food attracts vermin. The Viking ship’s cat was literally a life saver.

Fun fact: The Norse goddess Freya traveled in a carriage drawn by cats.

In ancient Skandinavian cultures, companion animals were laid to rest in elaborate burial mounds complete with favorite toys and treats. The Greeks and Romans of antiquity commissioned carved epitaphs expressing gratitude and deep sorrow over the loss of pets. Millions of animals did their part in the world wars. Jackie the Baboon helped fight the Great War as did Whiskey & Soda, the lion cub mascots of the Lafayette flying corps. “Vojtek” the Siberian brown bear accompanied Polish troops during World War 2.

Some 16 million Americans served in the Armed Services during World War 2. Nearly 300,000 were pilots. Only one of them, fighting to liberate Europe from the Nazi horde, was a coyote.

You must be logged in to post a comment.