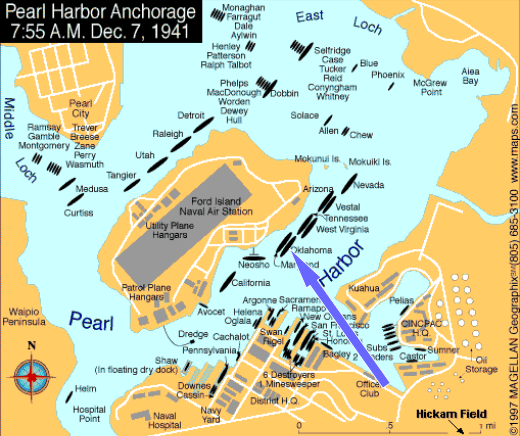

It was literally out of the blue when the first wave of enemy aircraft arrived at 7:48 local time, December 7, 1941. 353 Imperial Japanese warplanes approached in two waves out of the southeast, fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes, across Hickam Field and over the waters of Pearl Harbor. Tied in place and immobile, the eight vessels moored at “Battleship Row” were easy targets.

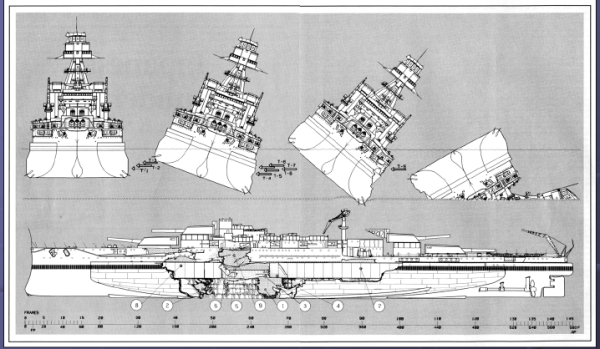

In the center of the Japanese flight path, sailors and Marines aboard the USS Oklahoma fought back furiously. She didn’t have a chance. Holes as wide as 40′ were torn into the hull in the first ten minutes of the fight. Eight torpedoes smashed into her port side, each striking higher on the hull as the Battleship began to roll

Bilge inspection plates had been removed for a scheduled inspection the following day, making counter-flooding to prevent capsize, impossible. Oklahoma rolled over and died as the ninth torpedo slammed home. Hundreds scrambled out across the rolling hull, jumped overboard into the oil covered, flaming waters of the harbor, or crawled out over mooring lines in the attempt to reach USS Maryland in the next berth.

The damage was catastrophic. Once the pride of the Pacific fleet, all eight battleships were damaged, and four of them sunk. Nine cruisers, destroyers, and other ships were damaged, and another two sunk. 347 aircraft were damaged, most caught while still on the ground. 159 of those were destroyed altogether. 2,403 were dead or destined to die from the attack, another 1,178 wounded.

Frantic around the clock rescue efforts began almost immediately to get at 461 sailors and Marines trapped inside. Tapping could be heard as holes were drilled to get to those trapped inside.

Only 32 were delivered from certain death. 14 Marines and 415 sailors lost their lives onboard Oklahoma, either immediately or in the days and weeks to come. Bulkhead markings later revealed that at least some of the doomed lived on in that pitch black, upside-down hell, waiting for rescue that would come too late. The last survivor drew the last such mark on Christmas Eve, 17 days after the attack.

Of sixteen ships lost or damaged, thirteen would be repaired and returned to service. USS Arizona remains on the bottom, a monument to the event and to the 1,102-honored dead who remain entombed within her hull. The USS Utah defied salvage efforts. She, too, is a War Grave, 64 honored dead remaining within her hull, lying at the bottom not far from the Arizona. Repairs were prioritized, and USS Oklahoma was beyond repair. She, and her dead, would have to wait.

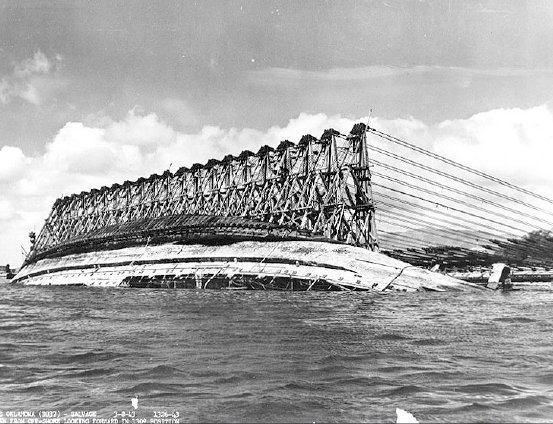

The extraordinarily difficult salvage at last began in March of 1943. 21 giant A-frames were fixed to the hull, 3″ cables connecting compound pulleys to 21 electric motors, each capable of pulling 429 tons. Two pull configurations were used over 74 days, first the configuration below, then direct connections once the hull had achieved 70°.

That May, the decks of USS Oklahoma once again saw the light of day.

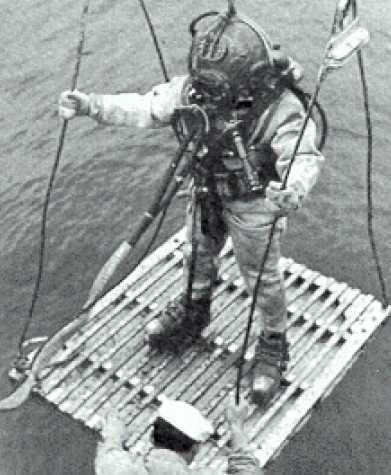

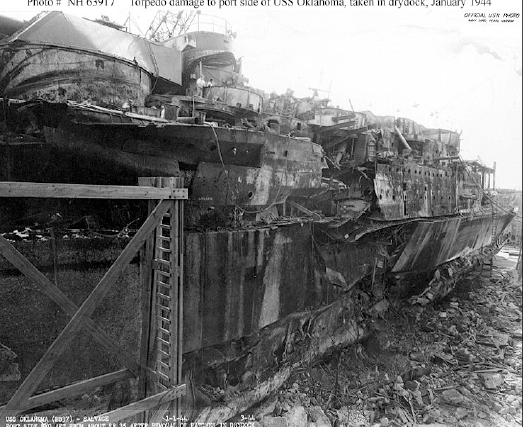

At last fully righted, the ship was now 10 feet below water. Massive temporary wood and concrete structures called “cofferdams” closed the gaping wounds left by torpedoes, so the hull could be pumped out and re-floated. A problem even larger than those torpedo holes were the gaps between hull plates, caused by the initial capsize and righting operations. Divers stuffed kapok in the gaps as water was pumped out.

Individual divers spent 2-3 years on the Oklahoma salvage job. Underwater arc welding and hydraulic jet techniques were developed during this period and remain in use to this day. 1,848 dives were performed for a total of 10,279 man hours under pressure. For all that, no military and only one civilian diver lost his life, that, when his air hose became severed.

Salvage workers entered the pressurized hull through airlocks wearing masks and protective suits. Bodies were in advanced stages of decomposition by this time, and the oil and chemical-soaked interior was toxic to life. Most victims were impossible to identify.

Twenty 10,000 gallon per minute pumps operated for 11 hours straight. On November 3, 1943, the ‘Mighty Okie’ broke from the bottom and once again floated on her own.

Oklahoma entered dry dock the following month, a total loss to the American war effort. She was stripped of guns and superstructure and sold for scrap on December 5, 1946, to the Moore Drydock Company of Oakland, California.

The battered hulk left Pearl Harbor for the last time in May 1947, headed for a scrapyard in San Francisco bay. She never made it. Taken under tow by the ocean-going tugs Hercules and Monarch, the three vessels entered a storm some 540 miles east of Hawaii.

On May 17, disaster struck. Piercing the darkness, Hercules’ spotlight revealed that the former battleship was listing heavily. Naval base at Pearl Harbor instructed them to turn around when these two giant tugs ground to a halt and found themselves moving… backward. Despite her massive engines, Hercules was being dragged astern, hurtling past Monarch, herself swamped at the stern and being dragged backward at 17mph.

Fortunately for both tugs, skippers Kelly Sprague of Hercules and George Anderson of Monarch had loosened the cable drums connecting 1,400-foot tow lines to Oklahoma. Monarch’s line played out and detached. With Oklahoma forever sunk beneath the waves and Hercules’ tow line pointing straight down, Hercules detached with a crash at the last possible moment, the 409-ton tug bobbing to the surface like the float on a child’s fishing line.

Ordered in March 1911 and launched three years later, the 583’ Nevada-class battleship USS Oklahoma was designed to fight at the most extreme ranges expected by gunnery experts. Commanded by Charles B. McVay, Jr., father of the ill-fated skipper of the USS Indianapolis Charles Butler McVay III, Oklahoma’s role in the Great War was limited, due to a shortage of oil in major theaters of operation. Notable among her exploits of WW1 were the memorable fist fights crew members got into with Sinn Féin members in Berehaven, County Cork, and casualties sustained during the 1918-19 flu pandemic.

Oklahoma was up-armored in a 1927 – ’29 refit. Additional anti-torpedo armor bulges were added, briefly making her the widest battleship in the United States fleet. Oklahoma was dispatched to Europe in 1936 to evacuate American civilians during the Spanish civil war.

The only US warship ever named after the 46th state, she was destroyed in an enemy sneak attack before she knew she was at war.

Of the 429 killed, 394 were buried as unknown persons. Since 2015, advances in forensic science and dna technology have led to the identification of 346. Many warships sunk during World War 2 have since been found. The final resting place of the USS Oklahoma remains, a mystery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.