In the ancient world, shadow-casting rods and obelisks tracked the time of day. The early Egyptians refined the method and created a sundial, followed by Babylonian, Greek, Chinese, and Mesoamerica versions of the device.

The Chinese monk Yi Xing is believed to have created the first mechanical clock, alongside scholar Liang Lingzan. Flowing water spun a wheel, driving a system of rods and levers marking time with a drumbeat every 15 minutes and a ringing a bell on the hour.

By the American colonial period, time tracking devices were relatively accurate. Time itself, however, was very much in the eye of the beholder.

As late as the 1880s, most towns in the US based local time on “high noon.” In an age when travel required days or weeks, it mattered little that the continent contained thousands of ‘time zones’.

The First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. The $1,000, months long trek across the country could now be completed in a week, at the cost of $150.

For passengers and cargo alike, railroads offered cost-effective, safe transportation of a sort unknown at that time.

The growth of the railroads was explosive. In 1871, the US had 45,000 miles of track. Between 1871 and 1900, another 170,000 miles were added to the nation’s inventory.

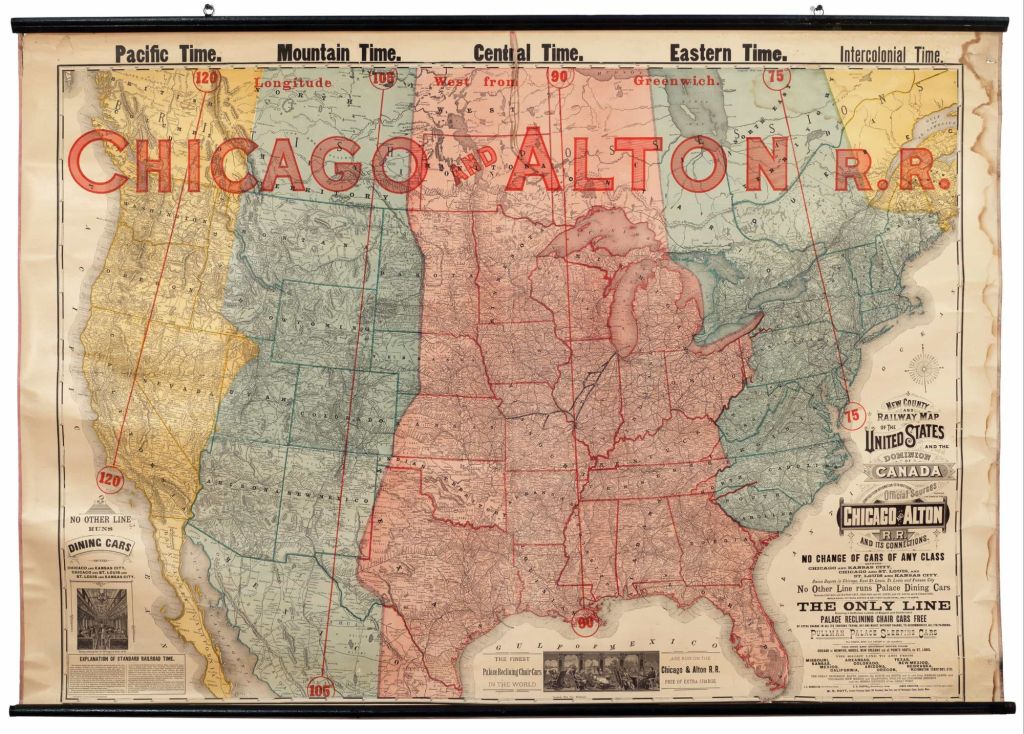

As to all those ‘time zones’, moving passengers and freight over thousands of miles meant no end of confusion. A single city could list dozens of arrival and departure times. Something had to change.

The railroad companies were powerful entities in those days. There was little need to turn to the government. So it was the railroads themselves divided the US and Canada into the time zones we know today.

The new system went into effect at precisely noon on November 18, 1883. Americans and Canadians alike were quick to adopt it.

Never ones to embrace innovation, Congress got around to ratifying the decision, approving the new system in 1918. Thirty-five years after the fact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.