Two miles off the Northeast coast of Great Britain lies the island of Lindisfarne, just south of the Scottish border. Once, there was a monastery there.

In the 7th century, the island’s monastic cathedral was founded by the Irish monk, Aidan of Lindisfarne. Known as the Apostle of Northumbria and spreading the gospel to Anglo-Saxon nobility and slaves alike, the monk was later canonized to become Saint Aidan.

Lindisfarne monastery had treasures of silver and gold, given in hopes that such gifts would find peace for the immortal soul of the giver. There were golden crucifixes and coiled shepherd’s staves, silver plates for Mass and ivory chests containing the relics of saints. Intricate tapestries hung from the walls. The writing room contained some of the most beautiful illuminated manuscripts ever made.

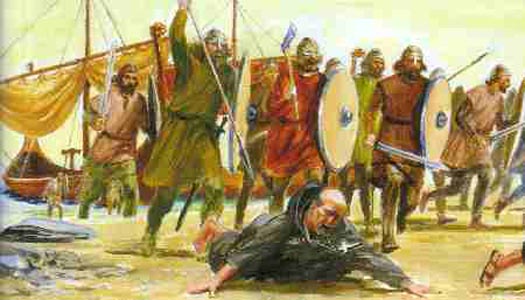

If you had looked out to sea 1,231 years ago to this day, you would have seen a strange sight. Long ships with high prow and stern were lowering square sail as oarsmen rowed the vessels directly onto the beach.

Any question you had as to their purpose would have been immediately answered, as the strangers sprinted up the beach and chased down everyone in sight. These they murdered with axe or spear, or dragged them down to the ocean and drowned them. Most of the island’s inhabitants were dead when it was over, or taken off to the ships to be sold into slavery. All of those precious objects were bagged and tossed into boats.

The raid on Lindisfarne abbey gave rise to what would become a traditional prayer: A furore Normannorum libera nos, Domine, “From the fury of the Northmen deliver us, Lord”.

The Viking Age had arrived.

Viking invasions were repeated until England was eventually bled of its wealth, and then they began to take the land.

It wasn’t just England either. The King of Francia was tormented by Viking raids in what would one day become western France. King Charles “the Simple”, so-called due to his plain, straightforward ways, offered choice lands along the western coast to these men of the north, if they would leave him alone. In 911 the Viking chieftan Rollo accepted Charles’ offer, and so created the kingdom of Normandy. They called him “Rollo the Walker”, because he was so huge that no horse to carry him, but that’s a story for another day. (Stay tuned in August)

A period of global warming during the 10th and 11th centuries created ideal conditions for the Norse raiders, with a prevailing westerly wind in the spring reversing direction in the fall to become west to east.

Viking travel was not all done with murderous intent; they are well known for colonizing westward as they farmed Iceland and possibly North America.

Many of their eastward excursions were more about trade than plunder. Middle Eastern sources mention Vikings as mercenary soldiers and caravan guards.

Viking warriors called “Varangian Guard” hired on as elite mercenary bodyguard/warriors with the eastern Roman Empire in Byzantium. Farther east, the “Rus” lent their name to what would later be called Russia and Belarus.

The 10th-century Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan described the Rus as “perfect physical specimens”, writing at the same time “They are the filthiest of all Allah’s creatures”. Tattooed from neck to fingernails, the men were never without an axe, sword, and long knife. The Viking woman “wears on either breast a box of iron, silver, copper, or gold; the value of the box indicates the wealth of the husband. Each box has a ring from which depends a knife”.

The classical Viking age ended gradually, and for a number of reasons. Christianity took hold, as the first archbishopric was founded in Scandinavia in 1103.

Political considerations were becoming national in scope in the newly formed countries of Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

King Cnut “The Great”, the last King of the North Sea Empire of Denmark, Norway and England, together also described as the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire, died in 1035, to be replaced in England by Edward the Confessor. Edward’s successor Harold would fend off the Viking challenge of Harald Hardrada in September 1066 at a place called Stamford Bridge, only to be toppled in the Norman invasion, two weeks later.

The Viking age lasted nearly 500 years, beginning in the late 8th century and ending only with the advent of the “Little Ice Age” in 1250.

In the end, the Vikings left their mark from Newfoundland to Baghdad.

You must be logged in to post a comment.