In the Spanish language, the word “Bobo” translates as “stupid…daft…naive”. The slang form “bubie” describes a dummy. A dunce. The word came into English sometime around 1590 and spelled “booby”, meaning a slow or stupid person.

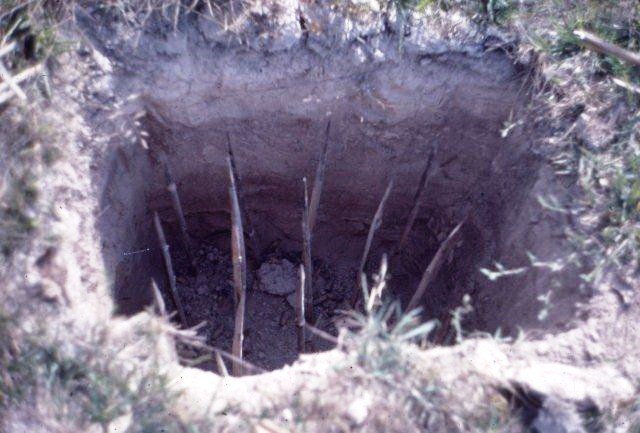

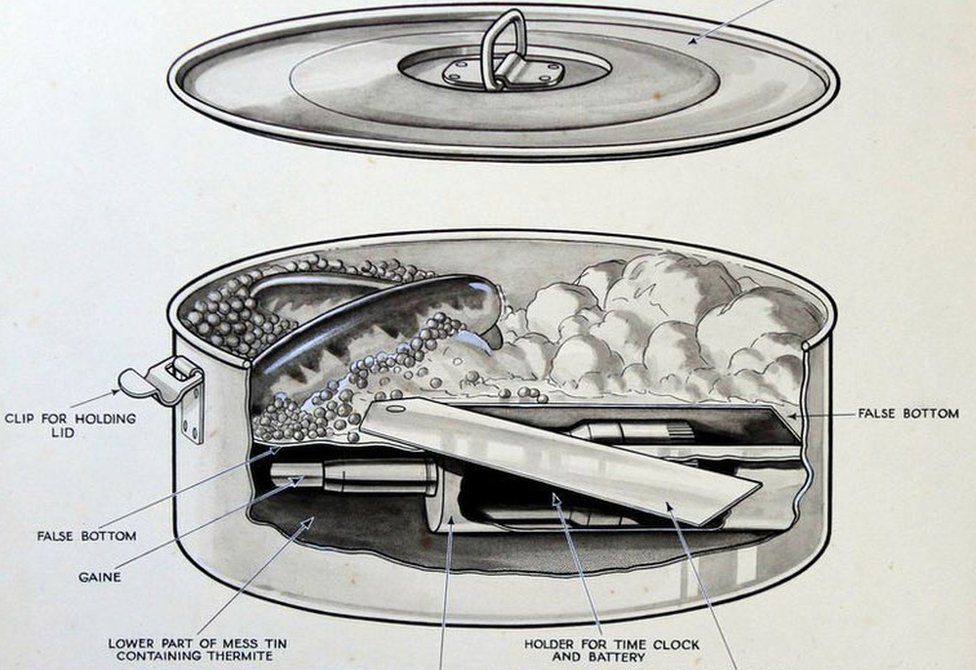

In a military context, a booby trap is designed to kill or maim the person who activates a trigger. Like the common mess tin at the top of this page, modified to mangle or kill the unsuspecting soldier. During the war in Vietnam, Bamboo pit vipers known as “three step snakes” (because that’s all you get) were tucked into backpacks, bamboo sticks or simply hung by their tails, a living trap for the unwary GI.

The soldier who goes to lower that VC flag might pull the halyard rope may hear distant snickering in the jungle…just before the fragmentation grenade goes off. Often, the first of his comrades running to the aid of his now shattered body hits the trip wire, setting off a secondary and far larger explosive.

Not to be outdone, the operation code-named “Project Eldest Son” involved CIA and American Green Berets sabotaging rifle and machine gun rounds, in such a way as to blow off the face the careless Vietcong shooter.

German forces were masters of the booby trap in the waning days of WW1 and WW2. A thin piece of fishing line connected the swing of a door with a hidden grenade, by your feet. A flushing toilet explodes and kills or maims everyone in the building. The wine bottle over in the corner may be perfectly harmless, but the chair you move over to get it, blows you to bits.

Virtually anything that can be opened or closed, stepped on or moved in any way can be rigged to mutilate or kill, the unwary. Fiendish imagination alone, limits the possibilities. Would the “Joe Squaddy” entering the room care if that painting on the wall was askew? Very possibly not but an “officer and a gentleman” may be moved to straighten the thing out at the cost of his hands, or maybe his life.

In the strange and malignant world of Adolf Hitler, the German and British people had much in common. Are we not all “Anglo-Saxons”? The two peoples need not make war the man believed, except for their wretched man, Winston Churchill.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill was a true leader of world-historical proportion during the darkest days, of the war. Taking the man out just might cripple one of Hitler’s most potent adversaries.

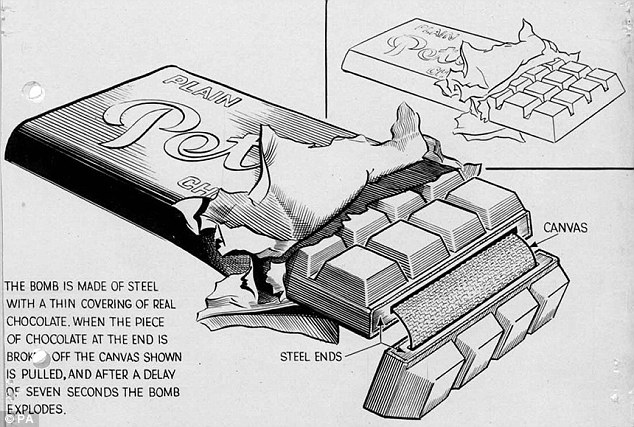

In 1943, Hitler’s bomb makers concocted an explosive coated in a thin layer of chocolate and wrapped in expensive black & gold foil labeled “Peter’s Chocolate”. When you break a piece off of this thing, you might wonder in the last nanoseconds of your life. What the hell is this canvas doing in a chocolate bar?

Churchill was known to have a sweet tooth and so it was, that Nazi Germany planned to kill the British Prime Minister. A booby trapped chocolate bar placed in a war cabinet meeting room.

We rarely hear about the work of the spy or the saboteur in times of war. They are the heroes who work behind enemy lines, with little to protect them but their own guts and cleverness. Their work is performed out of sight, yet there were times when the lives of millions hung in the balance, and they never even knew it.

The lives of millions, or perhaps only one. German saboteurs were discovered operating inside the UK, the information sent to British Intelligence.

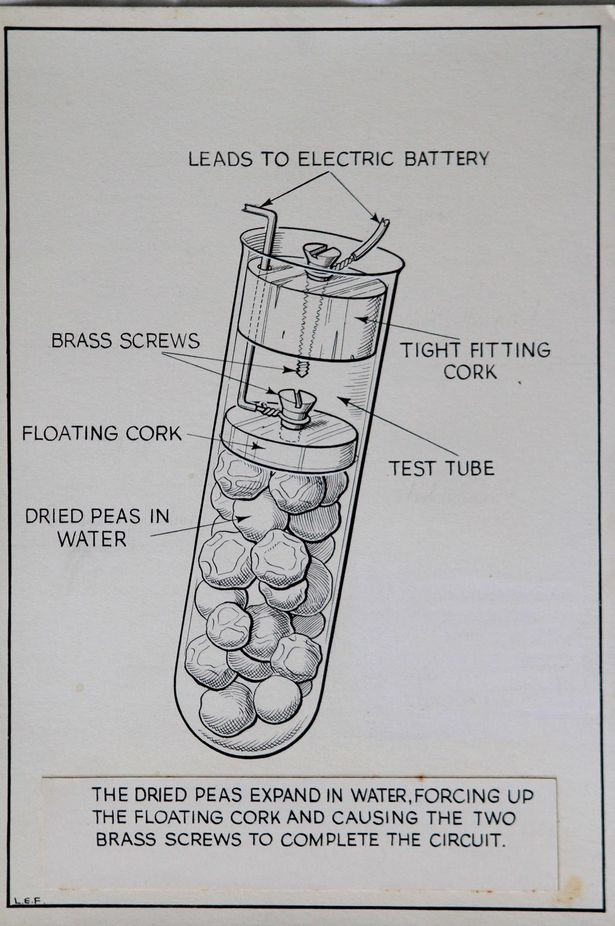

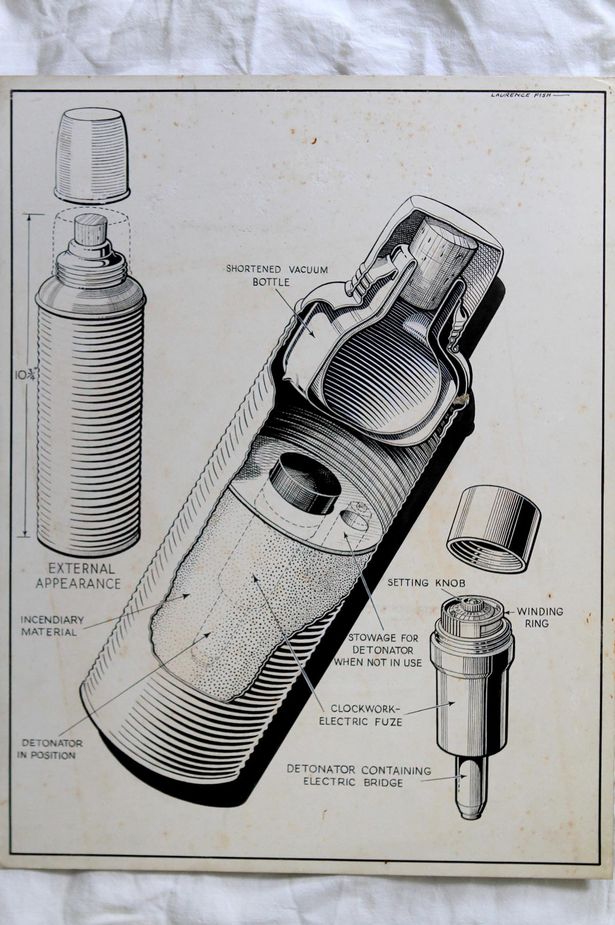

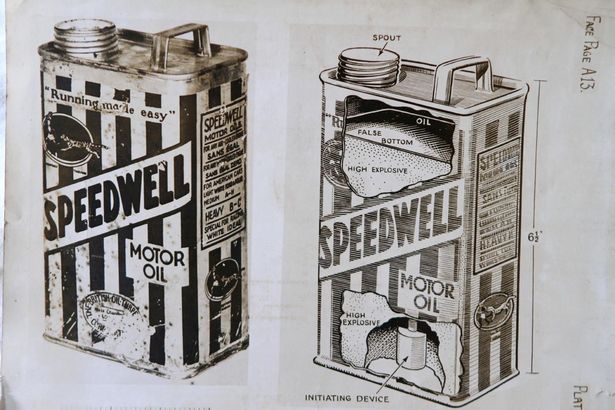

Lord Victor Rothschild was a trained biologist in peace and member of the Rothschild banking family. During WW2, British Intelligence recruited him to work for MI5, heading up a three-member explosives and counter-sabotage unit. Rothschild immediately grasped the importance of the information and the need to illustrate Nazi devices to communicate, with other intelligence officers.

We live in an age when computers are commonplace but that wasn’t the case, in 1943. ENIAC, the first electronic computer wouldn’t come around yet, for another two years. Photoshop was definitely out of the picture and yet, high quality illustrations were needed and quickly, and they had to come from a trusted source. Donald Fish, one of Rothschild’s two colleagues, had just the man. His son.

On this day in 1943, Lord Rothschild typed a letter to illustrator, Laurence Fish. The letter, marked “secret”, begins: “Dear Fish, I wonder if you could do a drawing for me of an explosive slab of chocolate…”

The letter went on to describe the mechanism and included a crude sketch, requesting the artist bring the thing, to life.

Laurence Fish would one day become a commercial artist and illustrator, best remembered for his travel posters of the 1950s and ’60s. He always signed his work, “Laurence”.

From the pen and ink technical drawings of the war years to the brightly colored travel posters of his post-war career, Laurence Fish was a gifted and versatile artist.

In 1943 that was all for some time in an unknown future, a time when dozens of wartime drawings were quietly left in a drawer and forgotten, for seventy years. For now a world had a war to win and Laurence Fish, played a part.

Hitler’s bomb makers devised all manner of havoc, from booby trapped mess tins to time-delay fuses meant to destroy shipping, at sea. In 2015, members of the Rothschild family were cleaning out the house, and discovered a trove of Fish’s work.

The artist is gone now and his name all but forgotten but his work, lives on. Fish’s illustrations are now in the hands of his widow Jean, an archivist and former journalist living in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire. Thanks to her we can see this forgotten piece of history in her husband’s work, last shown in an exhibition last year over the weekend of September 18 – 19.

And a good thing it is. The man has earned the right to be remembered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.