The Taiga occupies the high latitudes of the world’s northern regions, a vast international belt line of coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces and larches between the high tundra, and the temperate forest. An enormous community of plants and animals, this trans-continental ecosystem comprises a vast biome, second only to the world’s oceans.

The Eastern Taiga is a region in the east of Siberia, a vast, unexplored wilderness more than half again, the size of the continental United States. With snows lasting until May and resuming in September, there are no nearby oceans or seas to moderate temperature. Extremes are capable of summertime highs over 100° Fahrenheit (40c) to a wintertime low of -80° (-62c).

For all its size the region is all but unpopulated. Outside of a few towns the Siberian Taiga is home to no more than a few thousand. Siberia is also the source of vast Russian wealth in the form of oil, gas and minerals. In a wilderness capable of swallowing whole phalanxes of explorers there is hardly a district which hasn’t been overflown, at least once.

Helicopters and fixed wing aircraft cross huge tracts of arboreal forest carrying prospectors, workers and surveyors to and from remote backwoods camps.

So it was in 1978, the chopper descending with its team of geologists. Looking for a place to land near some unnamed tributary of the Abakan river, that trackless waterway with a name derived from the Khakas word, for “bear’s blood”. Treetops swayed in the propwash as the pilot peered downward, looking for a place to put down. And then he saw it. 100 miles from the Mongolian border and a good 150 miles from the nearest settlement. If those weren’t signs of human habitation, they sure looked like it.

Circling back, the pilot took another pass. And another. The Soviet government had no record of anyone living out here but, there it was. The clearing, 6,000 feet up the mountainside. The long furrows of a large garden. Someone had been growing here, for a very long time.

Ten miles away a four-person team of geologists, was there to explore for iron ore. The scientists thought they’d check it out. Packing what small gifts they could think of the team set out to investigate. The Russian writer, traveler and ecologist Vasily Peskov had once written, “It’s less dangerous to run across a wild animal (in these parts) than a stranger.” Geologist Galina Pismenskaya knew as much, and packed a gun.

As the four approached the spot described by the helicopter crew, there began to be signs. A worn path. A log laid across a stream. A rough shed filled with birchbark containers, with potatoes.

Pismenskaya describes what came next:

“…beside a stream there was a dwelling. Blackened by time and rain, the hut was piled up on all sides with taiga rubbish—bark, poles, planks. If it hadn’t been for a window the size of my backpack pocket, it would have been hard to believe that people lived there. But they did, no doubt about it…. Our arrival had been noticed, as we could see.

The low door creaked, and the figure of a very old man emerged into the light of day, straight out of a fairy tale. Barefoot. Wearing a patched and repatched shirt made of sacking. He wore trousers of the same material, also in patches, and had an uncombed beard. His hair was disheveled. He looked frightened and was very attentive…. We had to say something, so I began: ‘Greetings, grandfather! We’ve come to visit!’

The old man did not reply immediately…. Finally, we heard a soft, uncertain voice: ‘Well, since you have traveled this far, you might as well come in.’“

From the inside, the old man’s shanty was like something medieval. Dark, cramped and filthy, this was a single room under a roof propped up by sagging joists and a bare dirt floor covered with potato peelings, and pine nuts. Most astonishing of all this forest hovel out of a Grimm’s fairy tale turned out to be home, for a family of 5.

As eyes adjusted to the darkness the intruders spotted two women. Hysterical, quietly sobbing with terrified eyes and sinking to the floor, one of them praying, over and over. ‘This is for our sins, our sins. This is for our sins, our sins. This is for our…’

This wasn’t working. The four scientists quickly backed out and regrouped at a spot, a few yards away. Sitting down to eat they waited. A half-hour later the door once again, creaked open. Wary but curious like some wild thing the three emerged, and sat down with their visitors. There were small offerings, jam, tea, and bread, but always the same response. A shaking of the head and waving of the hand. “We are not allowed that“.

The old man spoke haltingly. The two sisters spoke to one another, in a manner which sounded like some kind of “blurred cooing”.

The story that emerged that day and over several more visits became more astonishing, by the minute. The old man, his name was Karp Lykov, was part of an old, fundamentalist Russian Orthodox sect, worshiping in a style unchanged since the time, of Czar Peter the great. Things went from bad to worse following the Russian Revolution, for the “Old Believers”. As the atheist Bolsheviks took power, countless numbers of Old Believers had fled into the wilderness, to escape persecution. Sometime in the 1930s a communist patrol had shot Lykov’s brother while Karp knelt beside him, working.

The Lykov family numbered 4 in 1936: Karp, his wife Akulina, a boy nine-year-old Savin, and Natalia, who was only two. Karp Lykov had to do something. The family scooped up some seeds and a few possessions and fled, into the forest. Over the years the family moved ever deeper, into the Taiga.

As the most destructive war in human history unfolded between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, an apocalypse known simply as the Ostfront, two more children were born in the wild. Dmitry in 1940 and Agafia, in 1943. The Lykovs missed World War 2 entirely without the slightest idea, of the outside world.

Life in the Taiga stood forever, at the brink of starvation. Roots, grass, potato tops. Every year the family meeting, whether to eat or save some of what they had, for seed. Dmitri grew hard, hunting barefoot in winter and possessed of preternatural stamina, capable of running wild animals to exhaustion and killing them, with his bare hands. With neither bow nor firearm, this was their only meat.

It snowed in June in 1961, killing their vegetables and setting the course, for famine. That was the year Akulina starved to death, preferring that her children eat. A single grain of rye managed to survive which the family guarded day and night, lest some wild animal eat their only hope.

Imagine. 42 years in that place without so much as a glimpse, into civilization. Nobody meant for it to happen but it was the outside world, which finally destroyed them.

Karp tried to keep it all, on the outside. The only gift he would accept was salt but, over time, the younger Lykovs gave in. Here a knife and fork and there an electric flashlight. None of them could take their eyes off the television, at the geologist’s camp.

The family went into decline. In the fall of 1981, three of the Lykov children died within days of each other. Savin and Natalia suffered from kidney failure, probably as the result of their harsh change in diet. Dmitri, the consummate outdoorsman who knew the Taiga in all her moods, succumbed to pneumonia, probably begun as an infection contracted from one of his new friends.

They tried to call him a helicopter but Dmitry would not leave his family. “We are not allowed that,” he murmured, just before he died. “A man lives for howsoever God grants.”

The geologists tried to persuade Karp and Agafia to come out of the wilderness, to rejoin those of their relatives who had survived the purges, of the Stalin regime. The answer was always, “no”.

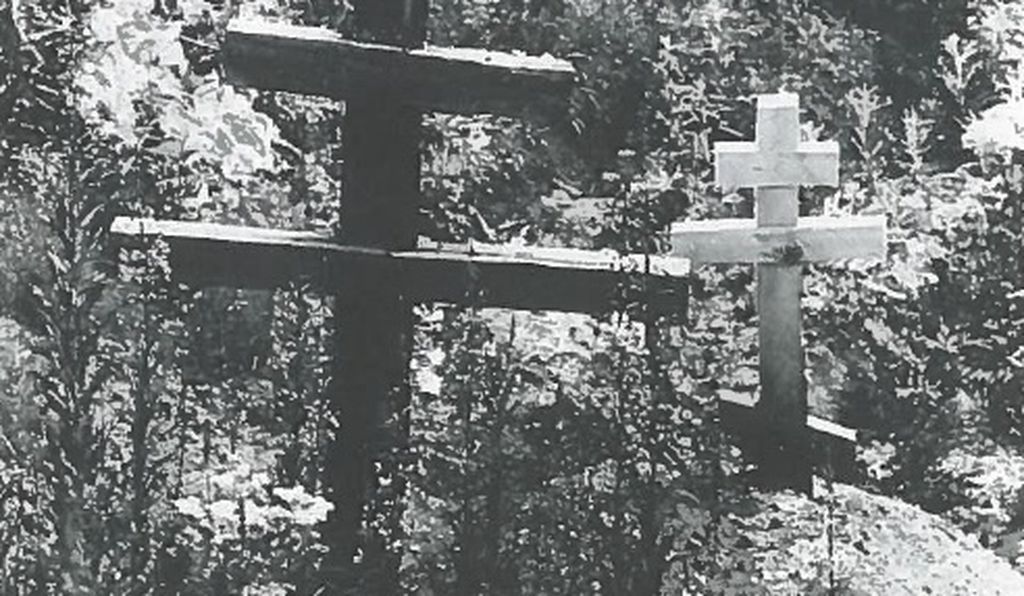

Karp Lykov died in his sleep on February 16, 1988. 27 years to the day from his wife, Akulina. Agafia buried him with the help of the geologists, on the mountainside, and then returned home.

Nothing lasts forever . There came that day when the visitors had to take their leave. One of the geologists, a driller named Yerofei Sedov, remembered: I looked back to wave at Agafia. She was standing by the river break like a statue. She wasn’t crying. She nodded: ‘Go on, go on.’ We went another kilometer and I looked back. She was still standing there.

Much of this tale comes from a 2013 article, in Smithsonian magazine. That’s where I got most of these images. At that time Agafia Lykova lived and perhaps yet lives, now approaching eighty, this child of the Taiga living alone, high above the Abakan.

how long does it take to make a essay this long??

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I’m somewhat familiar with the subject it can take as little as a couple hours. I usually, it’s more like three or four.

LikeLike

What a story, Rick. I’m glad I logged on today and was able to catch it. Great job retelling it, as always :)) Hope you are well ! Dawn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Dawn, it’s great to hear from you. I’m doing well over here. Hope we can all say the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLiked by 1 person