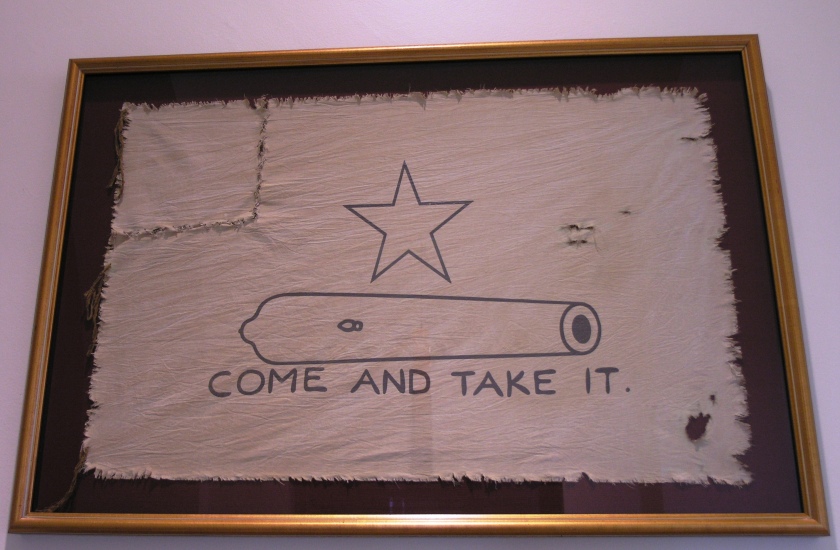

In 1831, Mexican authorities gave the settlers of Gonzales, Texas a small cannon, a defense against Comanche raids. The political situation deteriorated in the following years. By 1835, several Mexican states were in open revolt. That September, commander of “Centralist” (Mexican) troops in Texas Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, came to take it back.

Dissatisfied with the increasingly dictatorial policies of President and General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the colonists had no intention of handing over that cannon. One excuse was given after another to keep the Mexican dragoons out of Gonzalez, while pleas fr assistance secretly went out to surrounding communities. Within two days, 140 “Texians” had gathered in Gonzalez, determined not to give up that gun.

Militarily, the skirmish of October 2 had little significance, much the same as the early battles in the Massachusetts colony, some sixty years earlier. Politically, the “Lexington of Texas” marked a break between Texian settlers, and the Mexican government.

Settlers continued to gather, electing the well-respected local and former legislator of the Missouri Stephen F. Austin, as their leader. Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law, General Martin Perfecto de Cos to reinforce the settlement of San Antonio de Béxar, near the modern city of San Antonio. On the 13th, Austin led his Federalist army of Texians and their Tejano allies to Béxar, to confront the garrison. Austin’s forces captured the town that December, following a prolonged siege. It was only a matter of time before Santa Anna himself came to take it back.

Two forts – more like lonely outposts – blocked the only approaches from the Mexican interior into Texas: Presidio La Bahía (Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio) at Goliad and the Alamo at San Antonio de Béxar. That December, a group of volunteers led by George Collinsworth and Benjamin Milam overwhelmed the Mexican garrison at the Alamo, and captured the fort The Mexican President arrived on February 23 at the head of an army of 3,000, demanding its surrender. Lieutenant Colonel William Barret “Buck” Travis, responded with a cannon ball.

Knowing that his small force couldn’t hold for long against such an army, Travis sent out a series of pleas for help and reinforcement, writing “If my countrymen do not rally to my relief, I am determined to perish in the defense of this place, and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect.” 32 troops attached to Lt. George Kimbell’s Gonzales ranging company made their way through the enemy cordon and into the Alamo on March 1. There would be no more.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

The final assault began at 5:00am, on Sunday, March 6, 1836. 1,800 troops attacked from all sides. Santa Anna’s troops were shattered by concentrated artillery fire, but the numbers were overwhelming. The walls were breached and to hand fighting moved to the barracks, ending in the chapel. As many as seven defenders remained alive when it was over. Many believe former Congressman Davy Crockett was among them.

Santa Anna ordered them all, executed.

By 8:00am there were no survivors, saving a handful of noncombatant women, children, and slaves, slowly emerging from the smoking ruins. These were provided with blankets and two dollars apiece, and given safe passage through Mexican lines with the warning: a similar fate awaited any Texan who continued in their revolt.

On April 21, a force of 800 Texans shouting “Remember the Alamo!” and led by Sam Houston defeated Santa Anna’s force of some 1,500 at San Jacinto, near modern day Houston. The victory secured Texan independence. Mexican troops occupying San Antonio were ordered to withdraw by May. Texas became the 28th state of the United States on December 29, 1845.

Santa Anna went on to lose a leg to a cannon ball two years later, fighting the French at the Battle of Veracruz. following amputation, the leg spent four years buried at Santa Anna’s hacienda, Manga de Clavo, in Veracruz. When Santa Anna resumed the presidency in late 1841, he had the leg dug up and placed in a crystal vase, brought amidst a full military dress parade to Mexico City and escorted by the Presidential bodyguard, the army, and cadets from the military academy. This guy was nothing if not a self-promoter.

The leg was reburied in an elaborate ceremony in 1842, including cannon salvos, speeches, and poetry read in the General’s honor. The state funeral for Santa Anna’s leg was attended by his entire cabinet, the diplomatic corps, and the Congress.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna served 11 non-consecutive terms as Mexican President, spending most of his later years in exile in Jamaica, Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and St. Thomas. In 1869, the 74-year-old former President was living in Staten Island, trying to raise an army to return and take over Mexico City. In a bid to raise the money, Santa Anna brought the first shipments of chicle to the United States, a gum-like substance made from the tree species, Manilkara chicle. This, he proposed to use as rubber on carriage tires.

Thomas Adams, the American assigned to aid Santa Anna’s stay in the US, also experimented with chicle as a substitute for rubber. He bought a ton of the stuff from the General, but those experiments would likewise prove, unsuccessful. Instead, Adams helped to found an American chewing gum industry with a product he called “Chiclets”.

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History and commented:

What do the Alamo and Chewing Gum have in common?

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s interesting that they say the Texans fought for independence, because many men didn’t even live in Texas before the battles, I feel like there’s no recognition of that. case in point,

my 4x great grandfather James Trezevant fought in the Georgia Battalion, The flag was the white one with a blue star and says Liberty or Death . He was in college in columbia and attended , “Texas meetings” were held in Savannah and Walthoursville.

On November, 12, 1835 a meeting was held, in Macon. William A. Ward was the first of the twenty men to sign up, and he soon became their leader.

Other volunteers signed up in Millidgeville and Columbus.

Under the leadership of Ward the combined group headed overland for Montgomery, Alabama, so the Georgia Battlion and the Alabama Red Rovers came to fight.

James abruptly left college and went to Augusta to visit a girl friend. He had not yet joined the Georgia group, which had reached Montgomery. The group was given free passage down the Alabama River to Mobile and then went by steamer to New Orleans, Louisiana. That’s where James met up with his Battalion On December 9, 1835, Ward and his men embarked for Texas on several schooners, arriving at the port of Velasco on December 20.

On December 22, these original, mostly-Georgia volunteers organized officially as a military unit for the first time, calling itself the Georgia Battalion, with Ward as major and commander.

Three companies were formed, and James Trezevant was a private in Bullock’s Company. For the group from Macon, Georgia, this flag was made by an 18 year old girl, Joanna Troutman.

When the Georgians arrived at Velasco on the Texas coast the flag was raised.

It was one of the most inspirational symbols in the dark months between the defeat at the Alamo and the victory at San Jacinto.

After the Georgia battalion reported at San Felipe, Colonel William A. Ward, in command of the Georgians, led his men to the aid of Colonel Fannin at Goliad.

This flag was saluted again on March 8th, 1836, when Fannin’s men received word of the official declaration of independence of Texas. December 25, while still at Velasco, the Georgia Battalion presented itself for service to Colonel James W. Fannin, a fellow Georgian who was commander of all the volunteer troops in Texas.

Eventually, these troops were all stationed at Goliad, near the San Antonio River.

From there James fought in Ward’s Georgia Battalion at the Battle of Refugio on March 14, 1836.

With part of the Mexican army advancing north, General Sam Houston ordered Fannin to leave Goliad and go to Victoria.

Fannin ordered Ward, who had managed to evade the Mexican army while leaving Refugio, to meet him in Victoria.

Unfortunately, the Mexican army forced the surrender of Fannin and his men on March 20 after the Battle of Coleto.

They were taken back to Goliad as prisoners of war.

Meanwhile, Ward and his remaining men, numbering about eighty-five, evaded the Mexican army and eventually took refuge in the Guadalupe swamp near Victoria.

hile regrouping his men during the night of March 21, Ward inadvertently left behind eight men from the Georgia Battalion, one of whom was James Trezevant.

Ward and the remainder of his men were captured by the Mexican army on March 22 near Dimmit’s Landing.

They, too, were marched back to Goliad as prisoners of war, bringing the total number of prisoners there to about four hundred.

On Palm Sunday, March 27, 1836, most of them were gunned down by the Mexican army in what became known as the Goliad Massacre.

Virtually the entire Georgia command, the “Red Rovers” of Alabama and the Texans including Fannin, a total of almost 390 men, were taken prisoner and massacred at Goliad ,after they lost the battles of Refugio and Coleto.

Though some of its members escaped during the massacre itself, the Georgia Battalion ceased to exist. James Trezevant met up with three others from the swamp, Samuel G. Hardaway, Joseph Andrew, and M. K. Moses. After a number of days of living with no provisions, they were found by scouts from Houston’s army and taken to his camp on April 2.

From there they and the army set out toward Harrisburg, on Buffalo Bayou near the San Jacinto River.

The armies of Houston and Santa Anna finally confronted each other east of Harrisburg in the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. James fought as a private in Moseley Baker’s Company, along with Hardaway, Andrews and Moses.

At least four other men from the Georgia Battalion also fought in the battle. After San Jacinto, James joined Henry Karnes’s Spy Company, progressing in three months from private to lieutenant to captain and finally to brevet major.

During the summer and into the fall of 1836, he served as quartermaster of the commissary at the port of Velasco. He resigned his commission in the Texas army on November 19, 1836. James was still only twenty years old.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s an amazing story. Thank you for sharing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person