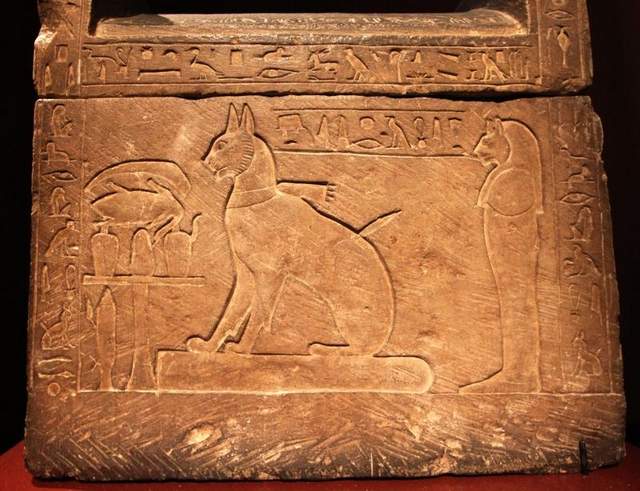

Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Felis silvestris catus suggests two great waves of expansion, first with the dawn of agriculture, when grain stores attracted vermin. Genetic analysis of the common house cat suggests they all descend from one of five feline ancestors: the Sardinian, European, Central Asian, Subsaharan African or the Chinese desert cat.

The second “cat-spansion” occurred later, as man took to water. From trade routes to diplomatic missions and military raids, men on ships needed food, and that meant rodents. The “ship’s cat” was a feature of life at sea from that day to this, first helping to control damage to food stores, ropes and woodwork and, in modern times, electrical wiring.

Fun fact: Who knew the Vikings had cats!

One Viking site in North Germany from ca 700-1000AD, contains one cat with Egyptian mitochondrial DNA. Once driven nearly to extinction, the Norwegian Forest cat (Norwegian: Norsk skogkatt) descends from Viking-era ship’s cats, brought to Norway from Great Britain sometime around 1000AD.

Not without reason, were cats seen as good luck. The power of cats to land upright is due to extraordinarily sensitive inner ears, capable of detecting even minor changes in barometric pressure. Sailors paid careful attention to the ship’s cat, often the harbinger of foul weather ahead.

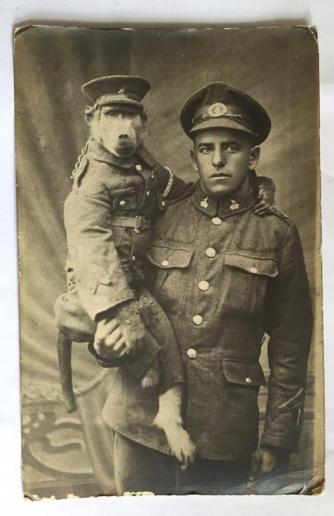

When the “Great War” arrived in 1914, animals of all kinds were dragged along. Cats performed the same functions in vermin infested trenches, as those at sea.

Tens of thousands of dogs performed a variety of roles, from ratters to sentries, scouts and runners. “Mercy” dogs were trained to seek out wounded on the battlefield, carrying medical supplies with which the stricken could treat themselves.

The French trained specialized “chiens sanitaire” to seek out the dead and wounded, and bring back bits of uniform. Often, dogs provided the comfort of another living soul, so the gravely wounded should not die alone.

With the hell of no mans land all but impassable for human runners, dogs stepped up, as messengers. “First Division Rags” ran through a cataract of falling bombs and chemical weapons. Gassed and partially blinded with shrapnel injuries to a paw, eye and ear, Rags still got his message where it needed to be.

Other times, birds were the most effective means of communication. Carrier pigeons by the tens of thousands flew messages of life and death importance, for Allied and Central Powers, alike.

During the Meuse-Argonne offensive of 1918, Cher Ami saved 200 men of the “Lost Battalion”, arriving in her coop with a bullet through the breast, one eye shot out and a leg all but torn off, hanging by a single tendon.

Even the lowly garden slug pitched in. Extraordinarily sensitive to mustard gas, “slug brigades” provided the first gas warnings, allowing precious moments in which to “suit up”.

The keen senses of animals were often the only warning of impending attack.

Private Albert Marr’s Chacma baboon Jackie would give early warning of enemy movement or impending attack with a series of sharp barks, or by pulling on Marr’s tunic.

Private Albert Marr’s Chacma baboon Jackie would give early warning of enemy movement or impending attack with a series of sharp barks, or by pulling on Marr’s tunic.

One of many wrenching images of the Great war took place in April, 1918. The South African Brigade withdrew under heavy shelling through the West Flanders region of Belgium. Jackie was frantically building a stone wall around himself, when jagged splinters wounded his arm and all but tore off the animal’s leg. Jackie refused to be carried off by stretcher-bearers, hobbling about on his shattered limb, trying to finish his wall

Constituted on June 13 1917, British Aero Squadron #32 kept a red fox, as unit mascot.

The famous Lafayette Escadrille kept a pair of lion cubs, called Whiskey and Soda.

German soldiers in Hamburg, enlisted the labor of circus elephants in 1915.

The light cruiser Dresden was scuttled and sinking fast in 1914, leaving the only creature on board to swim for it. An hour later an Ensign aboard HMS Glasgow spotted a head, struggling in the waves. Two sailors dove in and saved him. They named him “Tirpitz”, after the German Admiral. Tirpitz the pig served out the rest of the war not in a frying pan, but as ship’s mascot aboard the HMS Glasgow.

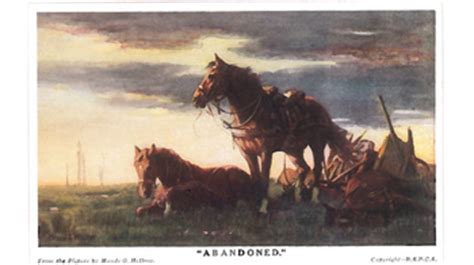

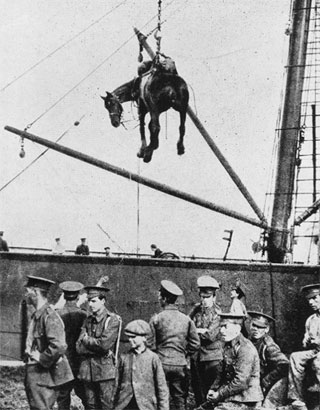

No beast who served in the Great war was as plentiful nor as ill used as the beast of burden, none so much as the horse. Horses were called up by the millions, along with 80,000 donkeys and mules, 50,000 camels and 11,000 oxen. The United States alone shipped a thousand horses between 1914 and 1917, every day.

Horsepower was indispensable throughout the war from cavalry and mounted infantry to reconnaissance and messenger service, as well as pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. With the value of horses to the war effort and difficulty in their replacement, the loss of a horse was a greater tactical problem in some areas, than the loss of a man.

Horsepower was indispensable throughout the war from cavalry and mounted infantry to reconnaissance and messenger service, as well as pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. With the value of horses to the war effort and difficulty in their replacement, the loss of a horse was a greater tactical problem in some areas, than the loss of a man.

Few ever returned. An estimated three quarters died of wretched working conditions. Exhaustion. The frozen, sucking mud of the western front. The mud-borne and respiratory diseases. The gas, artillery and small arms fire. An estimated eight million horses were killed on all sides, enough to line up in Boston and make it all the way to London four times, if such a thing were possible.

Few ever returned. An estimated three quarters died of wretched working conditions. Exhaustion. The frozen, sucking mud of the western front. The mud-borne and respiratory diseases. The gas, artillery and small arms fire. An estimated eight million horses were killed on all sides, enough to line up in Boston and make it all the way to London four times, if such a thing were possible.

The United Kingdom entered the war with only eighty motorized vehicles, conscripting a million horses and mules, over the course of the war. Only one in sixteen, lived to come home.

Neither knowing nor caring why they were there, the animals of the Great War suffered at prodigious rates. Humane organizations stepped up, the British Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) processing some 2.5 million animals through veterinary hospitals. 1,850,000 were horses and mules. 85% were treated and returned to the front.

The American Red Star Animal Relief Program sent medical supplies, bandages, and ambulances to the front lines in 1916, to care for horses injured at a rate of 68,000 per month.

The century before the Great War was a Golden age, mushrooming populations enjoying the greatest rise in living standards, in human history. The economy at home would be dashed to rags and atoms by the Great War. Trade and capital as a proportion of the global economy would not recover to 1913 levels, until 1993.

Unseen amidst the economic devastation of the home front, was the desperate plight of animals. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, carrying out over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

Dickin Medal

The “Dickin Medal” was instituted on December 2, 1943, honoring the work performed by animals, in WW2. The “animal’s Victoria Cross”, the highest British military honor equivalent to the American Medal of honor, is awarded in recognition of “conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units.”

The Dickin Medal has been awarded 71 times, recipients including 34 dogs, 32 pigeons, 4 horses and a cat. An honorary Dickin was awarded in 2014, in honor of all animals serving in the Great War.

Two Dickins were awarded on this day in 2007. the first to Royal Army Veterinary Corps explosives detection dog “Sadie”, a Labrador Retriever whose bomb detection skills saved the lives of untold soldiers and civilians in Kabul, in 2005. The second went to “Lucky”, a German Shepherd and RAF anti-terrorist tracker serving during the Malaya Emergency of 1949 – ’52. Part of a four-dog team including “Bobbie”, “Jasper” and “Lassie”, Lucky alone would survive the “unrelenting heat [of] an almost impregnable jungle“.

Handler Beval Austin Stapleton was on-hand to receive Lucky’s award. “Every minute of every day in the jungle” he said, “we trusted our lives to those four dogs, and they never let us down. Lucky was the only one of the team to survive our time in the Malayan jungle and I’m so proud of the old dog today. I owe my life to him.”

Ship’s cat, Her Majesty’s Australian Ship (HMAS) Encounter, World War I

Vikings had cats!! As if I didn’t have enough reasons to LOVE being a cat owner! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought you’d like that😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you sir

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are some really amazing stories in there- thanks for another fascinating post. From boosting morale to saving lives, it’s important to remember the animals that went “Over There” too. (I’d just been reading about the Dickin Medal too, for a post on a book about Judy, the only (I believe?) dog to be declared an official WW2 POW. )

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, my. That’s just the sort of “historical Easter egg” I like, and I don’t know the story. I’m going to have to look ol’ Judy up. Thanks for the heads up, and thank you for the kind words. All my best, Rick Long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know you’ve mentioned enjoying the dog stories in particular 😉 This is one of the books about her (though I haven’t checked it out yet) https://www.amazon.com/No-Better-Friend-Extraordinary-Survival/dp/0316337056/ref=pd_sbs_14_1/132-0049895-7077263?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=0316337056&pd_rd_r=4d34d3b6-2b4b-11e9-a095-811ee4313434&pd_rd_w=GBpp3&pd_rd_wg=S9tax&pf_rd_p=588939de-d3f8-42f1-a3d8-d556eae5797d&pf_rd_r=JHNJ1MJET35JEVRJG58G&psc=1&refRID=JHNJ1MJET35JEVRJG58G

LikeLike

Shoot- sorry for the huge link there!

LikeLike