All too often, history is measured in terms of the monsters. The ten worst dictators of the last 1½ centuries account for the loss of nearly 150 million lives. Most of us remember their names. At least some of them. Who remembers the name of the man who Saved the lives of seven times the number, of this whole Parade of Horribles, put together?

We live in a time and place where the National Institutes of Health (NIH) can report “The U.S. is one of the wealthiest countries in the world and accordingly has high obesity rates; one-third of the population has obesity plus another third is overweight”.

It wasn’t always so. In 1820, 94% of the world’s population lived in “absolute poverty.” American economic historian and scientist Robert Fogel, winner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote that: “Individuals in the bottom 20% of the caloric distributions of France and England near the end of the eighteenth century, lacked the energy for sustained work and were effectively excluded from the labor force.”

It’s hard to get the modern head around the notion of “food insecurity”. We’re not talking about what’s in the fridge. This is the problem of acute malnutrition, of epidemic starvation, of cyclical famine and massive increases in mortality, due to starvation and hunger-induced disease.

Nels Olson Borlaug once told his grandson Norman, “You’re wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” An Iowa farm kid educated during the Great Depression, Norman Ernest Borlaug periodically put his studies on hold, in order to earn money. A Civilian Conservation Corps leader working with unemployed people on CCC projects, many of his co-workers faced persistent and real, hunger. Borlaug later recalled, “I saw how food changed them … All of this left scars on me”.

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

Stakman was exploring special breeding methods, resulting in rust-resistant plants. The research greatly interested Borlaug, who later enrolled at the University of Minnesota, to study plant pathology under Stakman. Borlaug earned a Master of Science degree in 1940, and a Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics, in 1942.

Borlaug attempted to enlist in the military following the attack on Pearl Harbor, but his application was rejected under wartime labor regulations. He was put to work in a lab, doing research for the United States armed forces.

Between 1939 and ’41, Mexican farmers suffered major crop failures, due to stem rust. In July 1944, Borlaug declined an offer to double his salary, traveling instead to Mexico City where he headed a new program focusing on soil development, maize and wheat production, and plant pathology.

“Pure line” (genotypically identical) plant varieties possess only one to a handful of disease-resistance genes. Random mutations of rusts and other plant diseases overcome pure line survival strategies, resulting in crop failures. “Multi-line” plant breeding involves back-crossing and hybridizing plant varieties, transferring multiple disease-resistance genes into recurrent parents. In the first ten years Borlaug worked for the Mexican agricultural program, he and his team made over 6,000 individual crossings of wheat. Mexico transformed from a net-importer of food, to a net exporter.

In the early sixties, Borlaug’s dwarf spring wheat strains went out for multi-location testing around the world, in a program administered by the US Department of Agriculture. In March 1963, Borlaug himself traveled to India with Dr. Robert Glenn Anderson, along with 220-pounds of seed from four of the most promising strains.

The Indian subcontinent experienced minor famine and starvation at this time, limited only by the US’ shipping 1/5th of its wheat production into the region in 1966 – ’67. Despite resistance from Indian and Pakistani bureaucracies, Borlaug imported 550 tons of seeds.

American biologist Paul Ehrlich wrote in his 1968 bestselling book The Population Bomb, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over … In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich went on: “I have yet to meet anyone familiar with the situation who thinks India will be self-sufficient in food by 1971…India couldn’t possibly feed two hundred million more people by 1980.”

Ehrlich could not have been more comprehensively wrong.

Borlaug’s initial yields were higher than any other crop, ever harvested in South Asia. Countries from Pakistan to India to Turkey imported 80,000 tons and more of seeds. By the time of Ehrlich’s book release in 1968, massive crop yields had substituted famine and starvation, with a host of new problems. There were labor shortages at harvest, and insufficient numbers of bullock carts to haul it to the threshing floor. Jute bags were needed, along with trucks, rail cars, and grain storage facilities. Local governments even closed school buildings, to use them for grain storage.

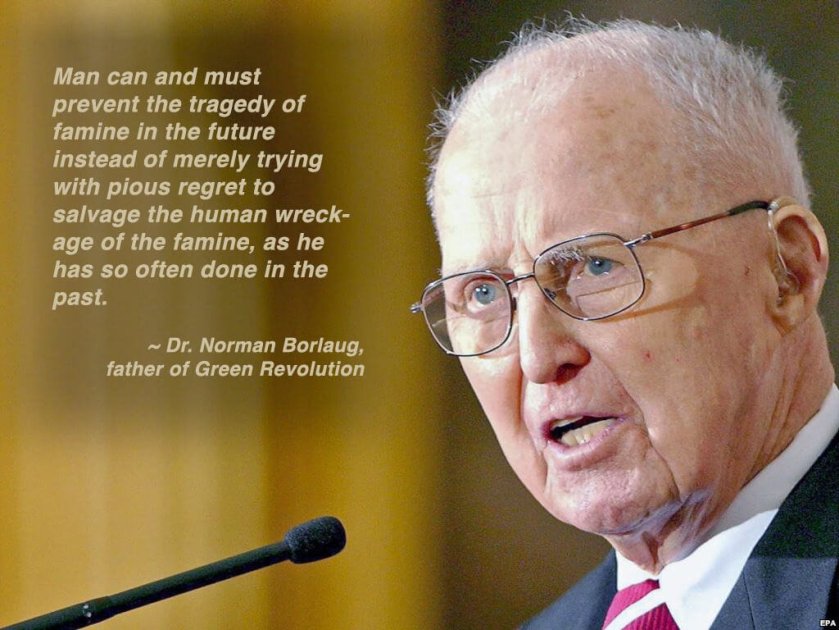

In three years, the world increase in cereal-grain production was nothing short of spectacular, dubbed a “Green Revolution”. Borlaug won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, protesting to be only “one member of a vast team made up of many organizations, officials, thousands of scientists, and millions of farmers – mostly small and humble…”

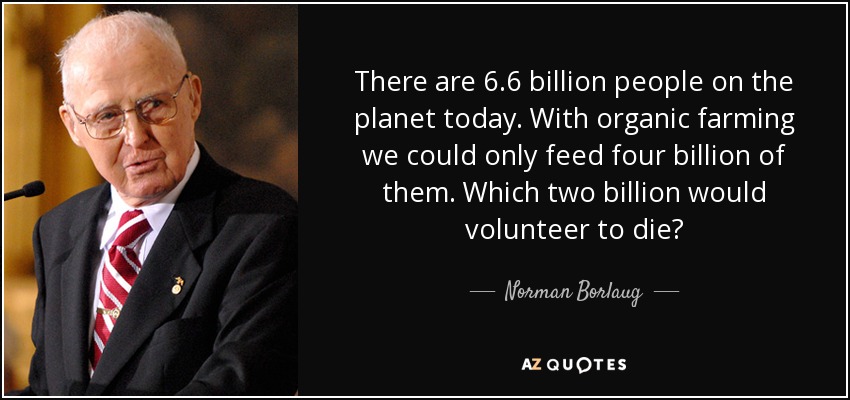

With mass starvation or widespread deforestation being the only historic alternatives, the “Borlaug Hypothesis” introduced a third option, that of increasing yields on existing farmland. The work however, was not without critics. Environmentalists criticized what they saw as large-scale monoculture, in nations previously reliant on subsistence farming. Critics railed against “agribusiness” and the building of roads through what had once been wilderness.

David Seckler, Director General of the International Water Management Institute said “The environmental community in the 1980s went crazy pressuring the donor countries and the big foundations not to support ideas like inorganic fertilizers for Africa.”

The Rockefeller and Ford foundations withdrew funding, along with the World Bank. Well fed environmentalist-types congratulated themselves on “success”, as the Ethiopian famine of 1984-’85 destroyed over a million lives. Millions more were left destitute, on the brink of starvation.

Borlaug fired back, “[S]ome of the environmental lobbyists of the Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists. They’ve never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they’d be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.“

Borlaug became involved at the invitation of Ryoichi Sasakawa, chairman of the Japan Shipbuilding Industry Foundation, who wondered why methods used so successfully in Asia, were not being employed in Africa. Since that time, the Sasakawa Africa Association (SAA) has trained over 8 million farmers in SAA farming techniques. Maize crops developed in African countries have tripled, along with increased yields of wheat, sorghum, cassava, and cowpeas.

The world population when Ehrlich released his book in 1968, was about 3.53 billion. Today, that number stands at 7.7 billion and, when we hear about starvation, such events are almost exclusively, man-made. The American magician and entertainer Penn Jillette once described Norman Borlaug as “The greatest human being who ever lived…and you’ve probably never heard of him.” Let that be the answer to the self-satisfied and well-fed, environmentalist types.

You had me at “an Iowa farm kid.” I grew up in Iowa! 🙂 A very nice piece, and yes you are right – a nice breath of fresh air from all the horror that history has!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did you ever hear of this guy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had not before! 🙂 I very much enjoyed learning

LikeLiked by 1 person

He’s from Cresco, Iowa. I have no idea where that is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Waaay Northeast 🙂 Practically on the border of Minnesota.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never trust anyone from Minnesota. They’re nuckin’ futts up there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Common sense isn’t as sexy to remember as a cause is…Great man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t that the truth. Especially when that cause can make someone feel good about themselves, from the comfort and safety of great distance.

LikeLiked by 1 person