The waterborne bacterium Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) lives in the warm waters of coastal estuaries and rivers, and the waters along coastal plains. Most of the time, those contracting the bacterium do so by consuming contaminated water, developing only mild symptoms or none at all.

Most times the infection resolves itself yet, at times, urban density has combined with poor sanitation, to produce some of the most hideous pandemics, in medical history.

The origins of Cholera, are unknown. The Portuguese explorer Gaspar Correa described a flare-up in the Ganges Delta city of Bangladesh in the spring of 1543, an outbreak so virulent that it killed most victims within eight hours, with a mortality rate so high that locals struggled to bury all the dead.

V. Cholerae populations undergo explosive growth in the intestines of the sufferer, releasing a toxin and causing cells to expel massive quantities of fluid. Severe cramps lead to “rice water” diarrhea and the rapid loss of electrolytes. Dehydration is so severe that it leads to plummeting blood pressures and often, death. It’s easy to see how the disease can “spike”. One such episode can cause a million-fold increase in bacterial populations in the environment, according to the CDC.

The first pandemic emerged out of the Ganges Delta in 1817, spreading to Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. 100,000 were killed on the island of Java, alone. The severe winter of 1823-’24 appears to have killed off much of the bacteria living in water supplies, but not for long.

The second Cholera pandemic began in 1830-’31, spreading throughout Poland, Russia and Germany. The disease reached Great Britain in 1832, when authorities undertook quarantines and other measures, to contain the outbreak.

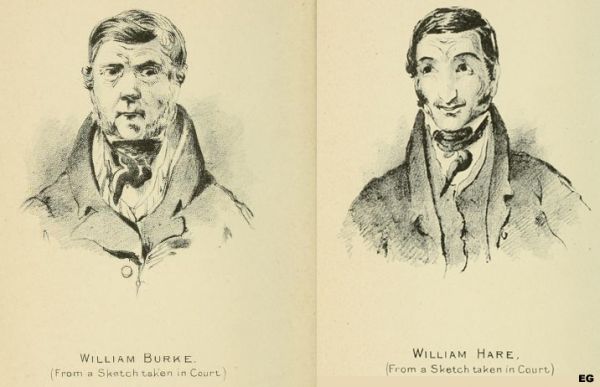

Four years earlier, William Burke and William Hare had carried out 16 murders over a ten-month period in Edinburgh, selling the corpses to Doctor Robert Knox for dissection during his anatomy lectures. Now, quarantines were met with pubic fear, and distrust of government and medical authorities. ‘Cholera riots’ broke out in Liverpool and London, with demands to ‘Bring out the Burkers”.

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

In 1760, the British capital of London was home to some 740,000 souls. One-hundred years later, population shifts had ballooned that number to nearly 3.2 million, in a city without running water.

At one time, the many farms surrounding the city of London used the, er…”stuff” provided by “Gong Farmers”, the ‘nightsoilmen’ whose execrable job it was to shovel out the growing numbers of cesspits throughout the city, for fertilizer. Transportation costs grew as the city expanded, and the farms moved away. In 1847, solidified bird droppings (guano) were brought in from South America at a cost far below that of the local stuff, leaving London’s poorer quarters increasingly, to their own filth.

The “Great Stink” of Victorian-era London is beyond the scope of this essay, save to point out that formal portraits may be found of Queen Victoria herself, with a clothespin on her nose. Today the topic is mildly amusing and not a little disgusting however, in an era before public sewage, we’re talking about life and death.

In 1854, police constable Thomas Lewis lived with his wife Mary and five-month-old Frances, at 40 Broad Street in the Soho neighborhood of London. The baby developed severe diarrhea over August 28-29, as Mrs Lewis soaked the soiled ‘nappies’ in pails of water. These she dumped into the pit in front of her house, as first her baby and then her husband, sickened and died.

The pit was three feet away from the Broad Street well, where much of the neighborhood came to pump drinking water.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

In the third century AD, the Greek physician Galen of Pergamon first described the “miasma” theory of illness, holding that infectious disease such as Cholera were caused by noxious clouds of “bad air”. Today the theory is discredited but, such ideas die hard.

Most everyone blamed the fetid air for the cholera outbreak, but Dr. John Snow was different. Snow suspected there was something in the water and, through door-to-door interviews and careful analysis of mortality rates, devised a ‘dot map’ identifying the Broad Street address.

“On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the [Broad Street] pump. There were only ten deaths in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street-pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad Street, as they preferred the water to that of the pumps which were nearer. In three other cases, the deceased were children who went to school near the pump in Broad Street …”

Snow himself believed in the Miasma theory of disease as did Reverend Henry Whitehead, who helped him collect his data. Yet somehow, the pair became convinced that infectious agents were somehow concentrated in the water, and they had found the “Index Case”.

Despite near-universal skepticism regarding Dr. Snow’s theories, the pump handle at 40 Broad Street was removed. It was later re-installed but, by that time, the danger had passed. Untold numbers of lives were saved by Dr. Snow’s intervention.

Dr. Snow succumbed to a stroke in 1858 and died at the age of 45, never learning how right he had been. Dr. Louis Pasteur opened his institute for the study of microbiology, thirty years later.

Today, the place is known as “Broadwick Street”. There’s a replica of the old water pump out front of #40, across from the John Snow pub. If you’re ever in London, stop and hoist a glass to an unsung hero. One of the Founding Fathers, of modern epidemiology.

Fascinating stuff, I shall look it up next time I’m in London.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating article -have you read the book “the Ghost Map?” It goes into this story in pretty amazing detail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did – as a matter of fact I own it in audio and just finished it, for the second time. I can’t explain why but there is something weirdly fascinating to me, at the point where epidemiology meets history.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Ah yes, I remember your excellent flu pandemic articles! Epidemiology is indeed a very interesting thing to study.

LikeLiked by 1 person