You’ve worked all your life. You’ve supported your family, paid your taxes, and paid your bills. You’ve even managed to put a few bucks aside, in hopes of a long and happy retirement.

The subject of currency devaluation is normally left to eggheads and academics, the very term sufficient to make most of us tip over and hit our heads on the floor, from boredom. But, what happens to that “nest egg”, if the cost of the coffee in your hand doubles in the time it takes, to drink it?

History records 58 such instances of hyperinflation. Current events in Venezuela constitute #59 despite the largest proven oil reserves on the planet, while certain American politicians and celebrity types, are nowhere to be found.

History records 58 such instances of hyperinflation. Current events in Venezuela constitute #59 despite the largest proven oil reserves on the planet, while certain American politicians and celebrity types, are nowhere to be found.

In antiquity, Roman law required a high silver content in the coinage of the republic. Precious metal made the coins themselves objects of value, and the Roman economy remained relatively stable for 500 years. Republic morphed into Empire over the 1st century BC, leading to a conga line of Emperors minting mountains of coins in their own likenesses. Slaves worked to death in Spanish silver mines. Birds fell from the sky over vast smelting fires, yet there was never enough to go around. Silver content inexorably reduced, until the currency itself collapsed in the 3rd century reign of Diocletian. An Empire and its citizens were left to barter as best they could, in a world where currency had no value.

The assistance of French King Louis XIV was invaluable to Revolutionary era Americans, at a time when American inflation rates approached 50% per month. Yet, French state income was only about 357 million livres at that time, with expenses exceeding one-half Billion. France descended into its own Revolution, as the government printed “assignat”, notes purportedly backed by 4 billion livres in property expropriated form the church. 912 million livres were in circulation in 1791, rising to nearly 46 billion in 1796. One historian described the economic policy of the Jacobins, the leftist radicals behind the Reign of Terror: “The attitude of the Jacobins about finances can be quite simply stated as an utter exhaustion of the present at the expense of the future”.

Somehow, that sounds familiar.

In the waning days of the Civil War, the Confederate dollar wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. Paper money crashed in the post-Revolutionary Articles of Confederation period as well, when you could buy a live sheep for two silver dollars, or 150 paper “Continental” dollars. Roles reversed and creditors hid from debtors, not wanting to be repaid in worthless paper money. Generations after our founding, a thing could be described as worthless as “Not worth a Continental”.

Germany was a prosperous country in 1914, with a gold-backed currency and thriving industries in optics, chemicals and machinery. The German Mark had approximately equal value with the British shilling, the French Franc and the Italian Lira, with an exchange rate of four or five to the dollar.

That was then.

While the French third Republic levied an income tax to pay for the “Great War”, the Kaiser suspended the gold standard and fought the war on borrowed money, believing he could get it back from conquered territories.

Except, Germany lost. The “Carthaginian peace” described by British economist John Maynard Keynes saddled an economy already massively burdened by war debt, with reparations. Children built ‘forts’ with bundles of hyperinflated, worthless marks. Women fed banknotes into wood stoves, while men papered walls. By November 1923, one US dollar bought 4,210,500,000,000 German marks.

The despair of the ‘Weimar Republic’ period resulted in massive political instability, providing rich soil for the growth of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (‘Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei’) of Adolf Hitler.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was also on the losing side, and broken up after the war. Lacking the governmental structures of established states, a newly independent Hungary began to experience inflation. Before the war, one US Dollar bought you 5 Kronen. In 1924, it was 70,000. Hungary replaced the Kronen with the Pengö in 1926, pegged to a rate of 12,500/1.

Hungary became a battleground in the latter stages of WW2, between the military forces of Nazi Germany and the USSR. 90% of Hungarian industrial capacity was damaged, half destroyed altogether. Transportation became difficult with most of the nation’s rail capacity, damaged or destroyed. What remained was either carted off to Germany, or seized by the Russians as reparations.

The loss of all that productive capacity led to scarcity of goods, and prices began to rise. The government responded by printing money. Total currency in circulation in July 1945 stood at 25 Billion Pengö. Money supply rose to 1.65 Trillion by January, 65 Quadrillion and 47 Septillion July. That’s a Trillion Trillion. Twenty-four zeroes.

The loss of all that productive capacity led to scarcity of goods, and prices began to rise. The government responded by printing money. Total currency in circulation in July 1945 stood at 25 Billion Pengö. Money supply rose to 1.65 Trillion by January, 65 Quadrillion and 47 Septillion July. That’s a Trillion Trillion. Twenty-four zeroes.

Banks received low rate loans, so that money could be loaned to companies to rebuild. The government hired workers directly, giving out loans to others and in many cases, outright grants. The country was flooded with money, the stuff virtually grew on trees, but there was nothing to back it up.

Inflation approached escape velocity. The item that cost you 379 Pengö in September 1945, cost 1,872,910 by March, 35,790,276 in April, and 862 Billion in June. Inflation neared 150,000% per day, making the currency all but worthless. Massive printing of money accomplished the cube root of zero. The worst hyperinflation in history peaked on this day in 1946, when the item that cost you 379 Pengö last September, now cost 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

The government responded by changing the name, and the color, of the currency. The Pengö was replaced by the Milpengö (1,000,000 Pengö), which was replaced by the Bilpengö (1,000,000,000,000), and finally by the (supposedly) inflation-indexed Adopengö. This spiral resulted in the largest denominated note in history, the Milliard Bilpengö. A Billion Trillion Pengö. The thing was worth twelve cents.

One more currency replacement and all that Keynesian largesse would finally stabilize the currency, but at what price? Real wages were reduced by 80% and creditors wiped out. The fate of the nation was sealed when communists seized power in 1949. Hungarians could now share in that old Soviet joke. “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”.

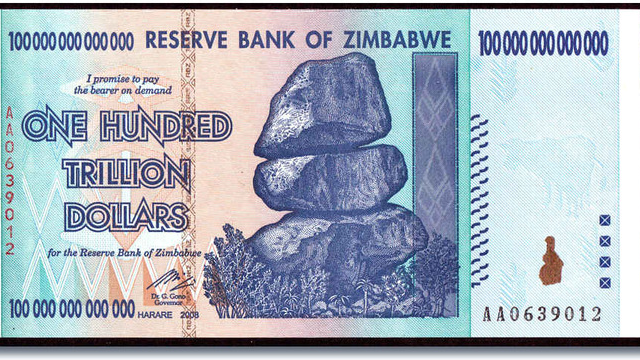

The ten worst hyperinflations in history occurred during the 20th century, including Zimbabwe in 2008, Yugoslavia 1994, Germany 1923, Greece 1944, Poland 1921, Mexico 1982, Brazil 1994, Argentina 1981, and Taiwan 1949. The common denominator in all ten were massive government debt and a currency with no inherent value, excepting what a willing buyer and a willing seller agreed it was worth.

The ten worst hyperinflations in history occurred during the 20th century, including Zimbabwe in 2008, Yugoslavia 1994, Germany 1923, Greece 1944, Poland 1921, Mexico 1982, Brazil 1994, Argentina 1981, and Taiwan 1949. The common denominator in all ten were massive government debt and a currency with no inherent value, excepting what a willing buyer and a willing seller agreed it was worth.

In 2015, Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff testified before the Senate Budget Committee. “The first point I want to get across” he said, “is that our nation is broke. Our nation’s broke, and it’s not broke in 75 years or 50 years or 25 years or 10 years. It’s broke today”. Kotlikoff went on to describe the “fiscal gap”, the difference between US’ projected revenue, and the obligations our government has saddled us with. “We have a $210 trillion fiscal gap at this point”. Nearly twelve times GDP – the sum total of all goods and services produced in the United States.

This morning, Treasurydirect.gov quotes US’ total outstanding public debt at $21,205,959,245,607.94, more than the combined GDP of the bottom 174 nations, on earth. All that, in a currency unmoored from anything objective value. What could go wrong?

The topics of your blog posts are far-ranging and fascinating. I have heard about hyper-inflation but seeing the details of what happened in Hungary, for example, is mindblowing. How do citizens continue to eat when money becomes worthless? I guess owning land on which one can grow food becomes a valuable option. And bartering takes over as a way to negotiate for goods and services between one’s fellow human beings? Although many people have read a book and/or seen a movie called “The Perfect Storm,” most of us haven’t grasped how this could easily happen on a national and also global scale. A new flu epidemic overlaps with destructive storms/flooding which then affect civil institutions (such as voting for political leaders) in unexpected ways. Add to the mix states using new voting apps which don’t work as planned and/or which can be hacked + climate-change-induced farming challenges + unexpected trade wars… and goodness knows how everything starts ricocheting! Please keep thinking and reflecting and writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I learn something new every time I read up to write these things. That makes it a weird geeky kind of fun all by itself but I especially enjoy when others share the same interests. Thanks for coming along for the ride.

LikeLike

Fascinating – and thought-provoking. The only episode I had any real knowledge of was Weimar Germany – though I’m obviously aware of the situations in Zimbabwe and Venezuela in a general way. Successive UK governments have been terrified of the prospect of high inflation since the 1970s and 80s…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m no economist but I have to believe that these things follow a logic if not a law of their own. My government has settled it’s taxpayers with so much debt that it actually scares me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The data here on debt to GDP ratios is fascinating. I am particularly struck by how the country with the highest debt to GDP ratio is… Japan, which has had a stagnating economy for decades but minimal inflation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

From what I can gather, the two common denominators in these hyperinflation episodes appear to be over-the-top debt, combined with irrational increases in money supply. All that seems to be required for the latter, Is some external event leading to a catastrophic loss of confidence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

here is data: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_public_debt

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Ian. According to this, the world’s sole remaining hyperpower owes 108% of the sum total of all goods and services produced by its entire economy, in a year. That does not begin to address the $200 trillion plus gap between projected obligations, and projected revenues. What could go wrong?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had only looked at the first column on the table and had not spotted how big the difference is between gross public debt as percentage of GDP and total gross government debt as percentage of GDP. I can’t quite make out what the difference derives from – maybe the larger figure includes debts incurred by the individual states and others subunits below the Federal government. I agree, the US figure here is pretty high.

I still don’t think hyperinflation is a a realistic worry for the United States. If the USA was to somehow find itself facing problems servicing its debts and was in danger of default it would most likely go cap in hand to the IMF for money and would then find itself in a structural adjustment programme, temporarily handing over economic sovereignty to the IMF & World Bank (both conveniently based in Washington). That would be no fun (my own country having gone through something similar in recent years) but you would be looking more at depression and deflation than hyperinflation.

I suppose the only way the IMF/World Bank would not be there to provide a bail-out to a USA facing debt problems would be if the USA to find itself with an eccentric President who had turned his back on US-designed multilateral international institutions, but something like that would never happen. So nothing to worry about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t see hyperinflation in the United States as any more than one possibility among others, however that May begin to change when other countries look at our debt to GDP ratio and begin to decline the opportunity to lend us more money. What we do face, with the certainty that night follows day, is a future of pouring $1 trillion +/- down a rat hole, paying interest we’ve already laid at the doorstep of our children and grandchildren.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The 1970s were unusual everywhere in that they saw relatively high inflation combined with economic stagnation (a phenomenon dubbed “stagflation”) – people had previously seen inflation as only occurring in expanding economies thanks to the demand bidding up prices.

LikeLiked by 2 people

At 77.4 the USA’s debt to GDP ratio is high-ish but not off the scale. I reckon debt-induced hyperinflation is not something the USA needs to particularly worry about.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hear that sentiment expressed quite a lot and I would like to believe it, but US debt trajectory appears to be headed in only one direction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hyperinflation generally and the German hyperinflation in particular is always a fascinating subject. A problem with the whole “hyperinflation led to the Nazis” thesis is that the Weimar hyperinflation came towards the beginning of the Weimar republic and was followed by years of prosperity and political stability before the Great Depression caused a collapse in living standards and a surge in support for extremist parties. One always hears that the hyperinflation undermined middle class support for democracy, but the Nazis were a marginal force until after 1929.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had a little trouble closing that loop in my own understanding. The peak period of the Weimar hyperinflation, 1923, coincided with the Beer Hall Putsch which sent Hitler and his core supporters to prison, but I’m a little shaky on the following ten years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some interesting thoughts. Whilst it’s true that huge economic and currency changes occurred in the Roman Empire, at the end of the 3rd Century, we can only say that the value of the currency declined. What this meant to the average citizen is difficult to determine, but some researchers say that the economy gradually morphed into something like our own – supported by vast numbers of low value coins (if you find a late Roman coin today, it’s probably valueless). Those same researchers think that this change resulted in more people getting involved in the monetary economy. The real collapse seems to have occurred in the late 4th Century, when supplies of minted coins dried up, and barter became the only option. As for the changes instituted by Diocletian, the arguments continue – did he do good or bad, and did the Empire expire because of severe economic / monetary problems? There probably isn’t a definitive answer.

LikeLiked by 3 people