During the late summer of 1854, 4,000 natives of the Brulé and Oglala Sioux were camped in the future Wyoming territory, near the modern city of Torrington, WY. On August 17, visiting Miniconjou High Forehead killed a wandering cow, belonging to a Mormon traveling the nearby Oregon trail. The native camp accorded with the terms of the treaty of 1851 and the cow episode could have been amicably handled, but events quickly spun out of control.

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

Chief Conquering Bear attempted to negotiate recompense, offering a horse or cow from the tribe’s herd. The owner refused, demanding $25. That same treaty of 1851 specified that such matters would be handled by the local Indian agent, in this case John Whitfield, scheduled to arrive within days with tribal annuities more than sufficient to settle the matter to everyone’s satisfaction.

Ignorant of this provision or deliberately choosing to ignore it, senior officer Lieutenant Hugh Fleming from nearby Ft. Laramie requested that the Sioux Chief arrest High Forehead, and hand him over to the fort. Conquering Bear refused, not wanting to violate rules of hospitality. Besides, the Oglala Chief had no authority over a Miniconjou.

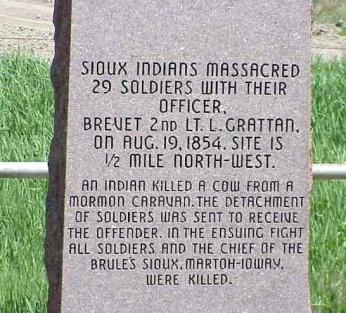

6th Infantry Regiment Second Lieutenant John Grattan arrived with a force of twenty-nine and a bad attitude, intent on arresting the cow’s killer. One Ft. Laramie commander later remarked, “There is no doubt that Lt. Grattan left this post with a desire to have a fight with the Indians, and that he had determined to take the man at all hazards.” French-Native interpreter Lucienne Auguste was contemptuous, taunting Sioux warriors as “women” and threatening that the soldiers had come not to talk, but to kill.

What followed was all but inevitable. Angry warriors took up flanking positions around the soldiers, one of whom panicked and fired, mortally wounding Conquering Bear. When it was over, all thirty soldiers were dead, their bodies ritually mutilated.

The Federal government was quick to respond to the “Gratton Massacre”, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis characterizing the incident as “the result of a deliberately formed plan.”

The first Sioux War of 1854 – ’56 became the first of seven major wars and countless skirmishes between the United States and various sub-groups of the Sioux people, culminating in the Ghost Dance War of 1890.

Diametrically opposite cultures steeped in mutual distrust engaged in savage cruelty each upon the other, often at the expense of innocents. There was even one major massacre of natives by other natives, when a war band of some 1,500 Oglala/Brulé Sioux attacked a much smaller group of Pawnee, during their summer buffalo hunt. Seventy-one Pawnee warriors were killed along with 102 of their women and children, their bodies horribly mutilated and scalped, some even set on fire.

Today, a 35-foot obelisk stands in mute witness, to the horrors of “Massacre Canyon”.

In the early eighteenth century, peoples of the Suhtai and Tsitsista tribes migrated across the northern Mississippi River, pushing the Kiowa to the southern plains and in turn being pushed westward, by the more numerous Lakota, or “Teton” Sioux. These were the first to adopt the horse culture of the northern plains, the two tribes merging in the early 19th century to become the northern Cheyenne.

The ten bands comprising the northern Cheyenne spread from the black hills of South Dakota, to the Platte Rivers of Colorado, at times antagonistic to and at others allied with all or part of the seven nations of the Sioux.

In 1866, the Lakota people went to war behind Chief Red Cloud, over Army encroachment onto the Powder River basin area, in northeastern Wyoming. The war ended two years later with the Treaty of Fort Laramie, granting a Great Sioux Reservation to include the western half of South Dakota including the Black Hills, as well as large, “unceded territory” in Wyoming and Montana and the Powder River Country, as Cheyenne and Lakota hunting grounds.

No whites were to be permitted onto these territories but for Federal Government officials, but the rich resources of the Black Hills, first in timber and then in gold, made the provision near-impossible to enforce.

The Army attempted for a time to keep settlers out of Indian territories, while political pressure mounted on the Grant administration to take back the Black Hills from the Lakota. Delegations of Sioux Chieftains traveled to Washington, D.C. in an effort to persuade the President to honor existing treaties, and to stem the flow of miners into their territories. Congress offered $25,000 for the land, and for the tribes to relocate south to Indian Territory, in modern-day Oklahoma. Chief Spotted Tail spoke for the whole delegation: “You speak of another country, but it is not my country; it does not concern me, and I want nothing to do with it. I was not born there … If it is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone.”

The government now determined to force the issue, and imposed a deadline of January 31. That many of the tribes even knew of such a time limit seems unlikely. The government’s response was unworthy of a Great Nation. On February 8, 1876, Major General Philip Sheridan ordered the commencement of military operations against those deemed “hostiles”.

The Great Sioux War of 1876-’77 began with a ham-fisted assault on the frigid morning of March 17, when Colonel Joseph Reynolds and six companies of cavalry attacked a village believed to that of the renegade Crazy Horse, but turned out to be a village of Northern Cheyenne.

A second, far larger campaign was launched that Spring, when three columns were sent to converge on the Lakota hunting grounds. Brigadier General George Crook’s column was the first to make contact, resulting in the Battle of Rosebud Creek on June 17. While Crook claimed victory afterward, the native camp was vastly larger than expected, and Crook withdrew to camp and wait for reinforcements. He had just taken his force out of what was to come.

General Alfred Terry dispatched the 7th Cavalry, 31 officers and 566 enlisted men led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, to begin a reconnaissance in force along the Rosebud. Custer was given the option of departing from his orders and going on the offence, should there be “sufficient reason”. For a man possessed of physical bravery bordering on recklessness – Custer had proven that thirteen years earlier at Gettysburg – there was bound to be sufficient reason.

Custer divided his force into three detachments, more concerned about preventing the escape of the “hostiles”, than with fighting them. It was a big mistake.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

The tale of those other two columns is worth a “Today in History” essay of their own if not an entire book, but this is a story about Little Big Horn. Suffice it to say that Major Marcus Reno‘s experience of this day was as grizzly and as shocking, as that moment when the brains and face of his Arikara scout Bloody Knife spattered across his own. Reno’s detachment had entered a buzz saw and would have been annihilated altogether, had it not met up with that of captain Frederick Benteen.

To describe what followed as “Custer’s last stand“ is to conjure images of soldiers fighting back to back, or crouched behind dead and dying horses amidst a swirling tide of warriors. Later archaeological evidence reveals not piles of spent casings marking the site of each man’s last desperate stand, but rather a scattering of brass across the hillside. Like a handful of rice, tossed across a hardwood floor.

2,500 warriors swept down on 268. There were no survivors.

The Battle of Little Big Horn, the Natives called it the “Battle of the Greasy Grass”, may be more properly regarded as the Indian’s last stand. Custer’s detachment was destroyed, to a man. Within hours, an enormous encampment of 10,000 natives or more were returning to their reservations, leaving no more than 600 in their place.

Crook and Terry awaited reinforcements for nearly two months after the battle. Neither cared to venture out again, until there were at least 2,000 men.

As I understand it , Custer’s men had two issues with their weapons. Faulty ammo( maybe, read various articles debunking that myth) and at that time, the goverment favored the trapdoor Sharps single shot rifle because they were cheaper to build, more reliable, more accurate/ greater range and kept the troops from wasting ammo. On the up side, the 45-70 is a motherf#cker! And still used to hunt big game in Africa. An extrenely accurate round/ rifle for its time…. I think twice the range of the other rifles tested….. Normally guys don’t get shot and die or fall down right away. Life ain’t the movies. Men have to bleed out. A big round like that is going to smash a lot of bone etc and travel all the way through a man, leaving a big wound channel and flowing a lot of blood. Ie speed up the bleeding out. Most men are shot in the arm or leg and a big round like that to an extremity increases the odds of knocking him out of action.

All that to say, I think their rifle was just fine. Everything is a trade off in combat and your pretty much out of luck when your 276 dudes run into 2000 dudes unless you have artillery, close air support and the ablity to bring in more men. Plus the Indians were probably better armed then we think. Or nerds were trending that way last I read.

Personally I think Custer’s men were doomed from the start because of the numbers and lack of effective communications/ command and control but would have taken more Indians with them to Valhalla if they were better armed. I seem to recall firearm training was pretty much non existent at that point, which negated the main advantage of the Sharps 45-70.

Side note, I have been all over Africa. I would eat anything I didn’t bring with me. #1 sanitation and refrigeration are pretty rare concepts. #2. Canablaism isn’t a particularity rare concpet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry not better armed but better trained

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe you’re right, Sergeant, and I think you’ve had more experience with this stuff, than most of us.

As I understand it, the Indians were armed with everything from clubs and spears, to modern repeating rifles. One in twenty possessed Winchester and/or Henry repeaters for a total of 200 such weapons. That alone may have tipped the balance in favor of the natives but, given the numbers, clubs alone may have been sufficient.

Custer’s people were armed with Springfield Model 1873 carbines and Colt single-action revolvers, chosen for reliability and “efficient use of ammunition”. If I’m not mistaken, Major Reno was on the final selection committee that chose these particular weapons.

Whatever anyone might like to think about Custer, the man had Cojones. He and about 450 Michigan cavalry waded into 2,000 Confederate horsemen on the third day at Gettysburg, routing J.E.B. Stuart’s force and possibly changing the outcome of the battle. I always wondered how it would have gone, had all that Confederate cavalry crashed into the rear of the Union lines near the “high water mark of the Confederacy”.

Thank you for your thoughtful comments and, more importantly, thank you for your service.

LikeLike

LOL yesterday I posted a comment about my specialization making me semi retarded on other issues. I am sure you know more about the battle in general.

Also i think the Indians were better armed then that. 200 repeaters and May be another 200+ other firearms

Custer was a yankee and I am not in the habit of saying positive things about those people

LikeLiked by 1 person

Uh oh. I live in the People’s Republic of Massachusetts now but I’m from Savannah. I hope the gets me a coupla redneck points.

LikeLike

Man talk about a culture shock!

I recently spent 3 weeks in Savannh. She is still beaitful but not the city of my youth when I was down there in the late 80’s

LikeLiked by 1 person

My daughter lives down there now. I don’t sound like it anymore but I go down there and that Spanish moss makes me feel at home.

LikeLike

Don’t forget the food

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating account of one of history’s most epic, but perhaps over romanticised, battles. It just goes to show what happens when people stop talking and begin to act without due thought.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Andy. I can’t say that I’m altogether happy with this one. It’s such an important part of our story over here – the conflict of cultures between natives and European settlers. Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass is steeped in mythology, but it’s only a single chapter in the book that is (are) the Sioux Wars of the 19th century, that volume only one amidst a vast library of stories. It’s a lot to take on 1000 words or so, and I think I could have done a better job in pulling it all together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is difficult sometimes to do the subject proper justice. I find the more I dig the more I want to write, but you have to draw a line somewhere. I tend to break larger ones down into parts, leaving the whole one as a separate page. Each part of history has a lot of separate avenues and to cover them all would take a book, or indeed, many, many books!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen to that, sir. I really have myself painted into a corner with this “Today in History“ format.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Small is beautiful as they say!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In my mind always lump together Little Big Horn with Isandlwana and Adwa, rare 19th victories against encroaching colonisers, with only Adwa being sufficiently decisive that it secured independence against the invaders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m actually unfamiliar with Adwa but I wholeheartedly agree as to the former. I’ve always thought the sights and sounds of a Zulu impi must have been terrifying to behold.

LikeLike

I’ve been to Ethiopia and seen many depictions of the Adwa battle (though not the site itself). The depictions may not have been entirely accurate as I do not think that St. George actually showed up to help the Ethiopians. The paintings are still interesting in terms of how countries portray their history, very similar to mediaeval Ethiopian art despite showing machine guns and cannons and typically including the leaders of 1896 Ethiopia (Emperor Menelik, Empress Taitu and Ras Makonnen, father of the future Haile Selassie) urging on their men to victory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was that the Italian campaign against the Ethiopians, or am I too early?

LikeLike

Adwa was 1896 when the Italians tried to invade. The campaign is an odd one, in that once each side had concentrated their forces they both wanted to fight on the defensive. The Italian general was put under massive political pressure to win a victory and eventually attempted to attack but were outfought by the Ethiopians and driven from the field after suffering heavy casualties (including the loss of several generals). Ethiopia’s independence was secured.

Fascist Italy had another crack at Ethiopia in the 1930s and with aeroplanes and mustard gas was able to overrun the country, but they were evicted by the British in 1941. Italians cultural influences nevertheless remain strong in Ethiopia: it seems like a good macchiato is to be had everywhere and tasty pasta dishes are also not uncommon though the local national cuisine is the best thing to eat there.

LikeLike

That’s a fascinating intersection between military and popular/culinary culture. Thank you, Ian. Cheers, Rick.

LikeLike

By an odd coincidence I was thinking of Little Big Horn earlier, when I was eating my dinner, because it popped into my head that one of the Indians who recalled the battle in later years said that there was no great last stand by Custer and that it was all over in the time it takes a hungry man to eat a meal.

I recall also reading that aside from their numerical advantage the Indians also had better rifles than the cavalry and could shoot Custer’s men at ranges from which the cavalry’s guns were ineffective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re right, Ian. If I have my facts straight, the native side was armed with everything from tomahawks and spears, to repeating rifles, of which there were about 200. Customers people were armed with single shot breechloader’s, and revolvers. I think they were probably rolled up and over in a matter of minutes. Native accounts seem to differ quite a lot, but the archaeological evidence leads me to that conclusion.

LikeLike

I’m guessing that Custer’s men’s firearms were the kind of thing that is normally fine for cavalry but not so good if you are in sustained firefight with infantry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ironically, the man had access to several Gatling guns but elected to leave them behind for fear of slowing himself down. That decision must go down as one of the great “oh shits”, of History.

LikeLike